Cutues are lazy. Politicians and architects insist every now and then on shaping a new landscape, but the physical inertia of their topography and character endow their urban matter with a tenacious memory that resists change. This routinary and efficient indolence of sites, similar to the hysteresis that ecologists invoke to explain morphological persistence in nature, contaminates the propositional enthusiasm of projects with a perfume of reality that either adapts them or discards them altogether. This is exactly what happened to the fancy proposal for a colossal avant-garde cultural complex amid the sheds of an old brewery close to Madrid’s Delicias station, built in the end as an inert storage for Legal Deposit books and the administrative files that the regional government bureaucracy so prolifically produces. And this is also the case of the old proposal for a tapestry museum beside the Royal Palace, which in its latest versions is gradually finding its place in Madrid’s cornice, and which is sure to undergo a further adjustment or two in order to adapt to the silhouette of the Manzanares acropolis.

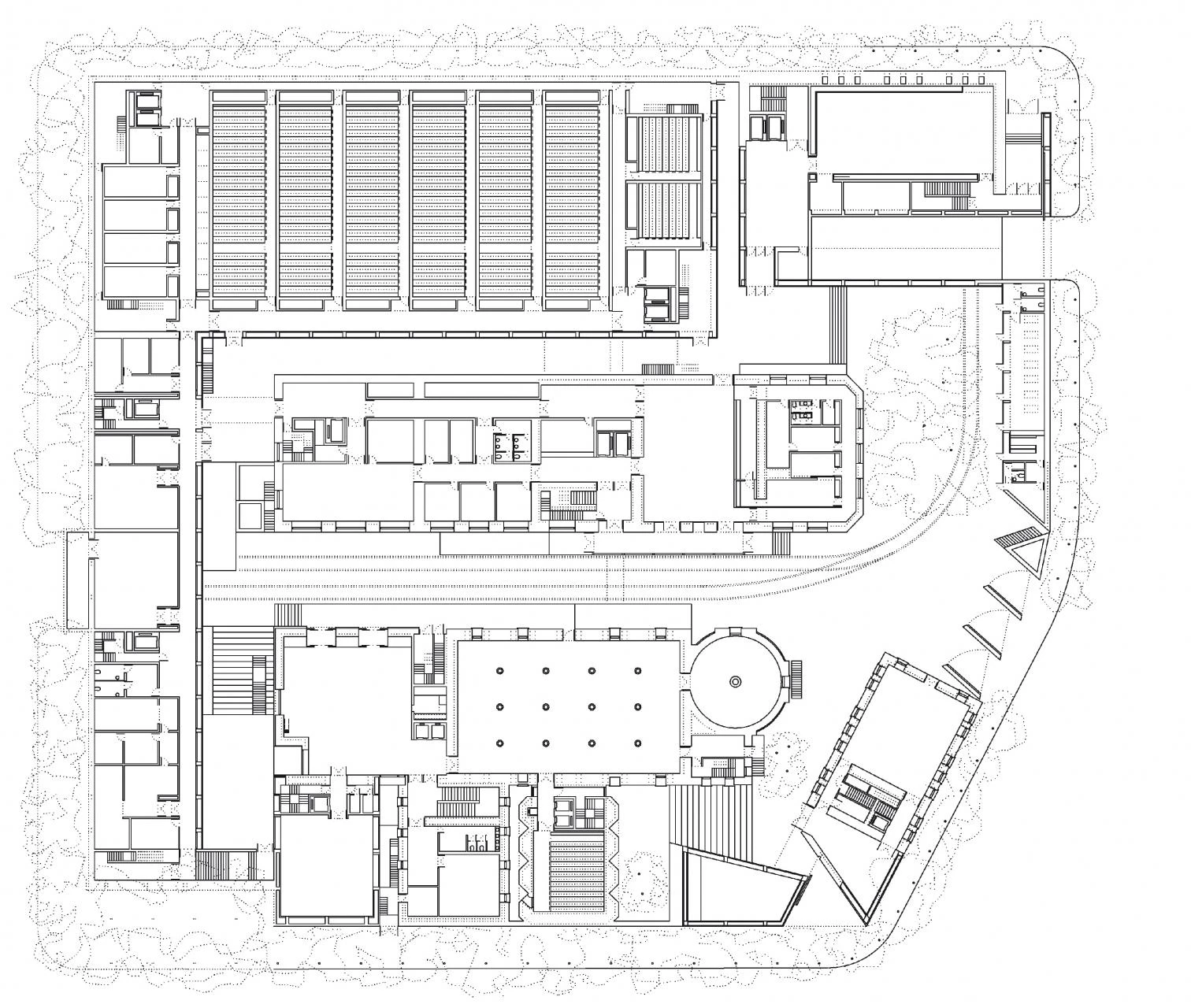

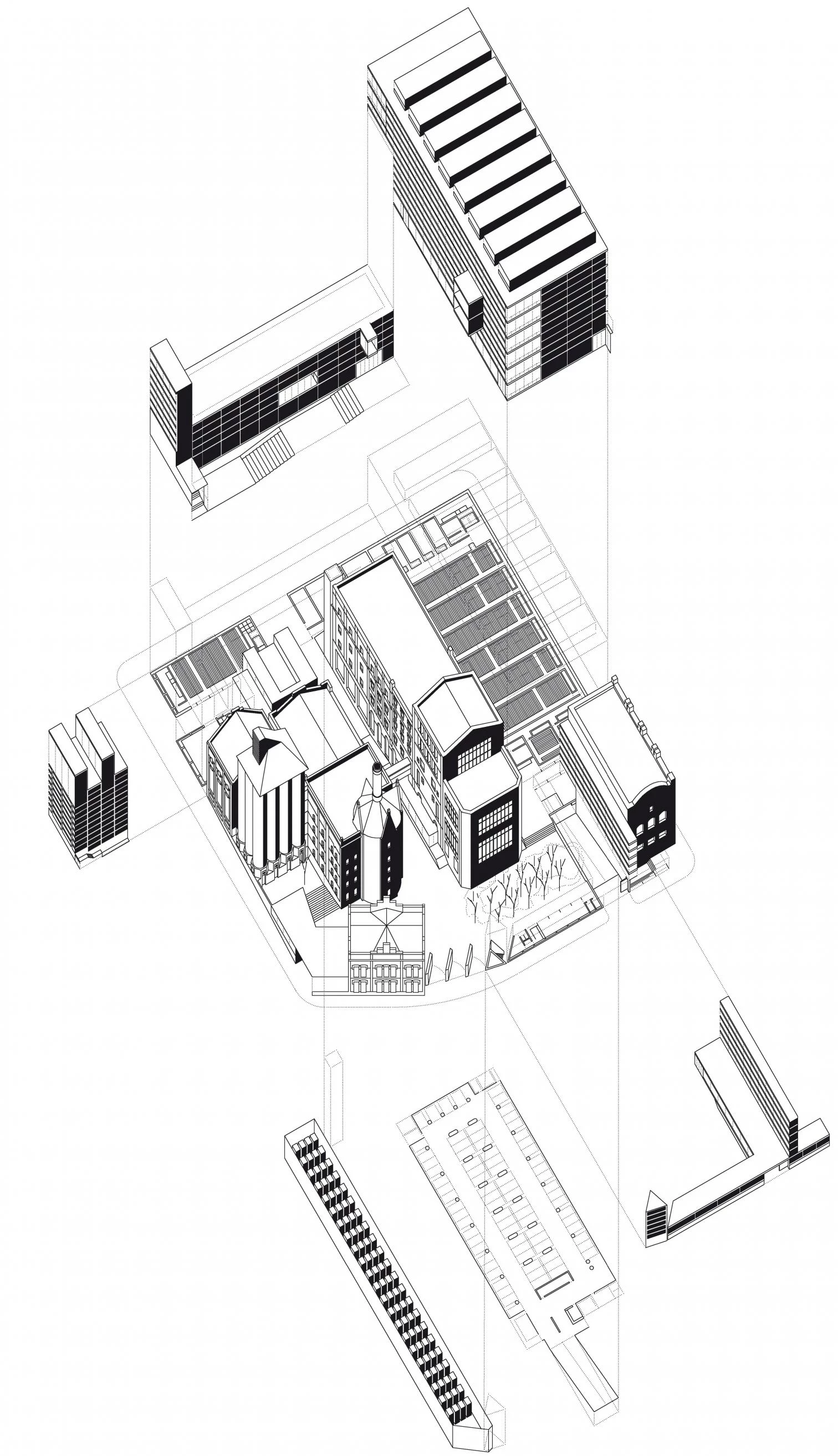

South of the center and next to the station of Atocha, the project of the regional archive and library composes an urban collage with new pieces and buildings of the old El Águila brewery.

In the physical and symbolic heights of the Spanish capital, the Museum of Royal Collections has been entrusted to Luis Moreno Mansilla and Emilio Tuñón, after an eventful competition that had originally taken the Cano Pintos brothers for winners, and which a Supreme Court ruling, by appeal of the architect Antonio Vázquez de Castro, had made it compulsory to repeat. This result had been particularly disappointing for the sons of the late Julio Cano Lasso, an architect of cautious modernity who drew the real and imaginary profiles of Madrid’s monumental cornice with thoughtful reiteration, and the fact is that the whole process was carried out by Patrimonio Nacional with such self-absorbed indecision and hermetic reserve that this national heritage organism has to take a large part of the blame for the muddle. Early on, in the presentation of 1999, Mansilla & Tuñón had proposed to undertake the museum without emptying the esplanade in front of the cathedral, locating it instead in the band that borders the platform, enlarged with a lot belonging to the church. Three years later, the lot had been acquired by Patrimonio, and the selected contestants – the Cano brothers no longer among them – were able to use Mansilla & Tuñón’s original idea as a starting point, and the final denouement of this confusing story has confirmed the strategic vision of the Madrid partners.

En el sur del centro y junto a la estación de Atocha, el proyecto del archivo y biblioteca regionales compone un collage urbano con piezas nuevas y edificios de la antigua fábrica de cervezas El Águila.

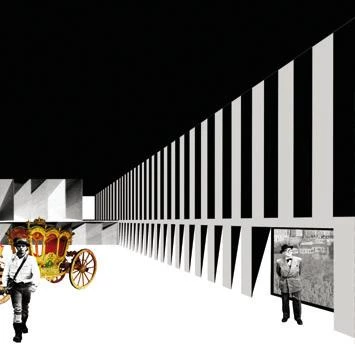

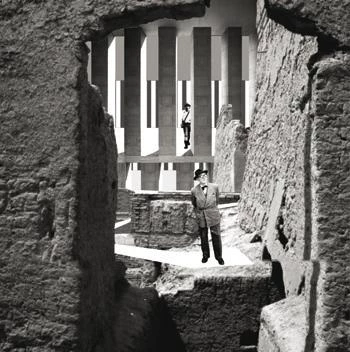

Conceived as a tight monumental latticework of large granite pillars that serve as a base for the square where the Almudena cathedral rises, the project is characterized by the impeccable and excessive logic of its clear-cut structural reiteration, and beyond trivial anecdotes like the theatrical golden entrance or the huge, pop-flavored free standing letters, the only thing open to criticism in its intelligent interpretation of the site’s topography is the categorical prismatic presence of the volume located above the level of the plaza, which by pulling up the museum to the height of the palace’s wings reduces the dramatic impact of the cathedral’s stepped volumes on that end of the cornice: with its 40,000 square meters, the building can afford to relinquish space and courteously incorporate itself into the lazy memory of the city, which can better metabolize it the more it assumes its role as a plinth.

From Palace to Brewery

Proof of Mansilla & Tuñón’s ability to listen to the hum of places is the complex they are currently wrapping up in Madrid’s Arganzuela district, an old brewery they have transformed into an archive and library with the rough severity and efficient execution that bespeaks its industrial past. In contrast to the archaic solemnity of the granitic monoliths in the court heights of the Palace, the run-down proletarian desolation of these mediocre neo-Mudejar constructions, beside the sad tracks of an obsolete train station, is interpreted with a distracted collage of concrete and glass prisms that interlock with the meticulous brick naves and the careened cylinders of the metal silos. Elegant and efficient, the complex is executed by the architects with the compact aplomb previously displayed in their Zamora and Castellón museums, and only the polychrome caprice of six tones of red used to decorate the fenestration of the archive facade – taken from I Send You this Cadmium Red..., a dispensable epistolary volume of the alternately lucid and tearful John Berger – allows the literary and artistic interests of the architects to seep through the cracks of a building otherwise conceived with solid constructive and functional persuasion.

The refurbishment respects the past of the building and incorporates industrial-like materials and furniture: the concrete and glass are reconciled with the brick warehouses and the metallic silos.

The 1994 competition that marked the beginnings of this work envisioned a huge cultural center that could stretch the museum area of the Paseo del Prado all the way down to the southern railwayridden district of Delicias, but the naive voluntarism of the politicians ran aground in the wise, reluctant inertia of the city, which transformed the volcanic “Leguidú” – an echo of the Parisian Pompidou, after the name of the former regional president –into a routinary Joaquín Leguina Library, the definitive name of an institution that now opens to the public, together with a large regional archive and a modest exhibition gallery for the neighborhood. Once scenario of the tango between Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón and his socialist predecessor in the presidency of the region of Madrid, the El Águila complex opens its doors at a time when the ambitious and brilliant conservative politician returns to the Popular Party flock – competing for the post of mayor with Ana Botella, the prime minister’s wife, on the ticket – and it becomes necessary to stump all traces of his former naughty conduct, blurring this toast to working class values. But the city’s indolence had already taken care of giving this heteroclite storehouse of books and documents the lowly and bureaucratic character that suits its environment and function, creating a still life that only the elderly in search of heating and newspapers or the young with their class notes will redeem from its prescribed immobility or stagnation.

Beside cathedrals and palaces or amid factories and railway tracks, the high city and the low are segregated landscapes that individual wishes hardly alter. Assuming this stubborn urban resistance, it is characteristic of architectural talent to be able to interpret diverse scores, as Mansilla & Tuñón have done in these disparate places. By now professionally mature, they have demonstrated a capacity to compete in adaptability with their master Rafael Moneo, and also perhaps with their current client Ruiz-Gallardón, who, like a tennis player, nimbly shifts left and right to always end at the center, that spot of uncertain balance that holds the key to public opinion, great ballots and great project.