Renzo Piano Construction Workshop, Children's Palliative Care Center, Bologna (Italy)

Do you know who wrote this? On 7 August 2021, Renzo Piano sends me a picture of the laconic interior of his refuge in the Alps, another of the bucolic view from his window, and a third of a yellowish press cutting with lots of underlines. Can it be a text by him? It is. It appeared in El País on 14 June 2003 under the title ‘Feria de vanidades,’ and I send him the full article along with views from our house in Zahara de los Atunes, on the Atlantic shore. I am glad to know it was you, it is very interesting, and helps all of us remember what truly matters and what does not matter at all! We have to talk, I miss you in these troublesome times. Renzo calls shortly afterwards and explains that his preoccupation with what matters and what does not comes from his experience of the pandemic and from the challenge of designing six new hospitals at the same time: three in Greece financed by the Niarchos Foundation, two in Italy, and the largest one in France, in the north of Paris. He recently finished a children’s hospital in Uganda, to be published next month in Arquitectura Viva, but is now totally focused on the six European projects.

A month later I receive in Madrid a thick envelope containing documents on the six hospitals, marked with yellow post-its filled with penmanship and accompanied by a letter written in Genoa and dated 2 September, where in his characteristic green calligraphy Renzo presents the projects emphasizing that all are low-emission (some of them zero-emission), in addition to pursuing technical and human excellence, and reiterates the invitation to have a talk about something he is very worried about. We Skype on the 13th – shortly before flying to Los Angeles to open the Academy Museum, with the spectacular bubble photographed by Iwan Baan – and Renzo describes the hospitals in progress, dwelling on the pediatric hospice in Bologna, nearly complete, and the center for transplants that he will be building close to Palermo for the University of Pittsburgh. He tells me that in every one of them he pursues the Vitruvian triad, taking firmitas as sustainability, utilitas as the public-spirit ethic that abbreviates the Latin term pietas, and venustas inevitably as beauty, summing up his endeavor as “being useful in the making of a better world.”

We agree to arrange for a longer conversation, and while Laura Mulas and Stefania Canta discuss dates and details for the publication of the hospital projects, we program a magazine issue featuring his latest works in Hollywood, Moscow, New York, and Paris. But nothing prepares us for the surprise we get on 28 January 2022, a monumental wooden box containing eight cardboard boxes on top of each of which Renzo has handwritten the contents: the six hospitals we have been talking about, the Uganda one we have already published, and a last box with two precursors, the ARAM Module carried out in 1970 with Richard Rogers and the hospital design guide put together in 2000 for Italy’s Health Ministry, and two related projects, the neuroscience facility at Columbia University, completed in 2015, and the public health research institute at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, currently under construction. The big box comes with a letter of 23 January in which Renzo admits that the enclosed material, as preparation for a chat, is “far too much,” but he assures me that half the effort to put it together was done for himself, absorbed as he is by the hospital theme, and reminds me that we should continue our talk, an invitation he repeats in a new note dated 2 February. We finally get around to it on the 15th of that month and pursue the themes put down in the two messages, which I transcribe verbatim with notes taken in the course of the conversation.

“I am, in this moment humanly, technically, and artistically absorbed by hospitals. Places of passion, of pathos, also suffering and emotion, places where time stops and you hold your breath. Hospitals are also places where science and technology unfold, where civics and ethics are fundamental, and where beauty can cure. My first project was with Richard Rogers, before Beaubourg. It was a portable module for a rural medicine association based in Washington, and twenty years ago I wrote a report on hospital design for my friend Umberto Veronesi, health minister then, which highlighted the indispensable human excellence of the architectural project. In Ancient Greece, before the appearance of medical science, hospitals were called Asclepeion and were places of beauty because of the nature around, the climate, the proportions, the light… but beauty has now been sequestered by marketing and become something frivolous.

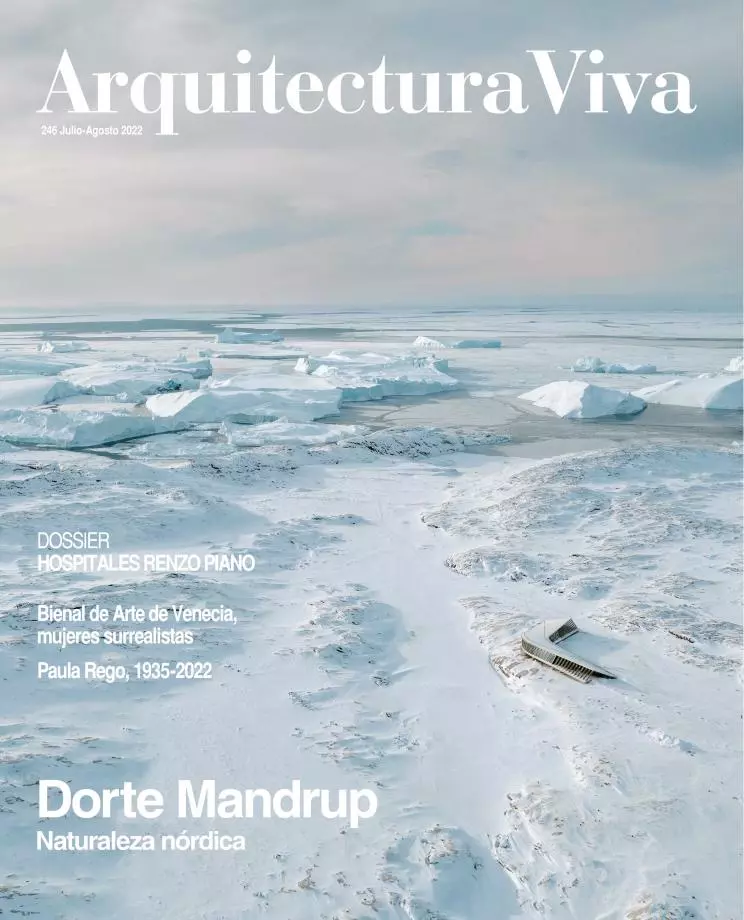

“The Bologna hospice for the palliative care of terminally ill children is a very difficult project, and what we’ve done is raise it above the ground in the woods, pursuing the beauty of the kind of compassion that makes you fall on your knees, with the surrounding trees providing a metaphor for healing. But in the 20th century we have erected monoliths, buildings ten or more stories high, when pavilions of three at most would be preferable and perhaps the thing to do is to get the best of both models: the humanity of the 19th century and the functionality of the 20th. As we’ve often discussed, our profession has been betrayed by an obsession with fashion, it has forgotten about life and we ought to bring back its lost dignity. In Paris, which is a dangerous place, I will be building a large hospital where the distance between floors is 4.5 meters (3 free, 1.5 for MEP services), although 4.8 would have been better. In Beaubourg it was 6 meters, guaranteeing flexibility in the face of change and the future, and after all the Centre Pompidou closes for renovation every 25 years: culture transformed after ’68, but Beaubourg did not change museums, it simply made the change visible.

“The same is bound to happen with hospitals, which will have to adapt to changes in medical science and technology with light compact buildings that explain and celebrate it. In Uganda, for example, the children’s hospital does it through vegetation, the jacaranda tree, and the material, earth. In the one that I’m building in Greece close to the Turkish border, and where the emergency services will be free of charge because people should be equal in sickness and in health, the material is wood. And in Paris it’s ceramic, always in pursuit of a certain hygiene that distinguishes hospitals from offices, schools, or museums. The hospital is a serious place where life is on hold, as in an apnea attack, and also a poetic place where miracles happen, so it can’t be all rational. In the end, places of dignity that celebrate human life. My friend Sebastião Salgado, who is my neighbor in Paris, has just published a book about the Amazon in which he explains that in the tribes that inhabit this impenetrable rainforest, the most important person is the architect, the one in possession of building skills. It’s the miracle of the shelter, and I would like this same respect for our profession.”

In Canto XXVI of Purgatory, Dante praises the poet Arnaut Daniel, whom he describes as “il miglior fabbro.” T.S. Eliot uses the same formula in dedicating The Wasteland to Ezra Pound, and I cannot think of a better term to describe the author of the hospitals contained in the box of this story.