Assault on the National Congress of Brazil by decision of Jair Bolsonaro

In a new epiphany of unease, a crowd chose a symbolic building as a frame for its protest. On 6 January 2021, Trump supporters stormed into the United States Capitol to try to overturn the election of Biden; and on 8 January 2023, Bolsonaro followers broke into the National Congress of Brazil in an attempt to cancel Lula’s win. The two largest countries in America, whose 332 and 210 million inhabitants add to over half of the continent’s population, expressed in this way the ideological, political, and emotional division caused by the erosion of institutions, a process that also affects several European countries, including our own. The collapse of the historic political parties in Italy or France, and the dysfunctions of the widely admired British democracy, are echoed in the growing polarization of the public sphere in Spain, which saw mass protests blocking the access to the parliaments of Madrid or Barcelona, and now witnesses the tarnishing of dialogue inside.

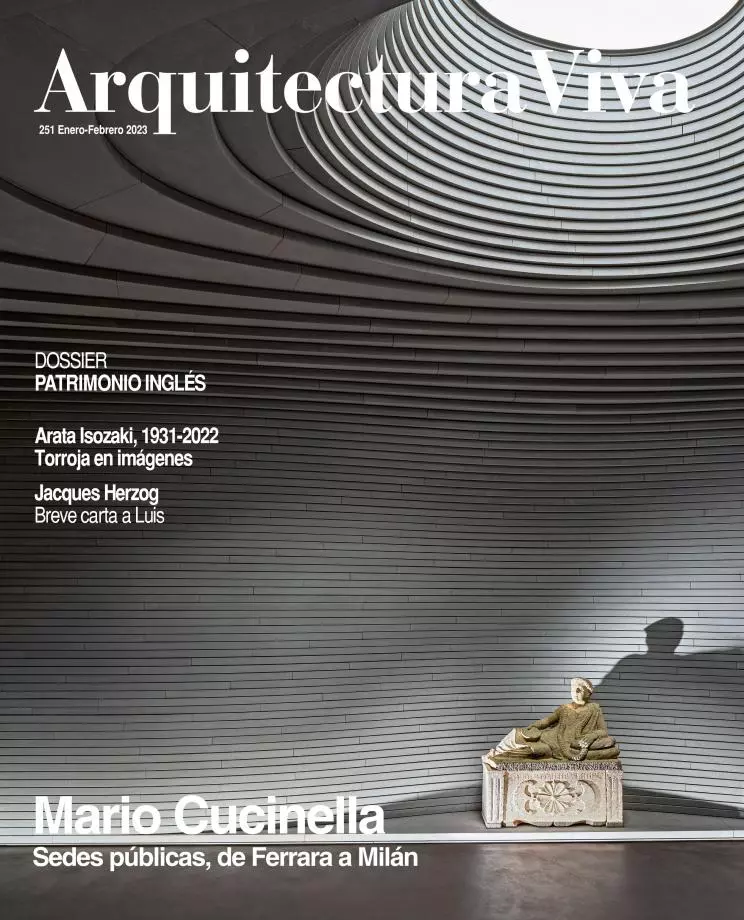

The beauty of the images showing protesters dressed in the colors of the flag and spread out on the ramps and platforms of the Congress like the chorus in a titanic opera should not confuse us, because that same seduction can be found in the Nuremberg Nazi rallies, with press photographers taking on today the role of Leni Riefenstahl and the material architecture of Niemeyer supplying the order that at the Zeppelinfeld was provided by military discipline and by Speer’s Cathedral of Light. The mob that at the Three Powers Plaza also assaulted the Supreme Court and the Palacio dó Planalto also offered images of vandalism that cannot aesthetically compete with those crowned by the dome of the Senate or the bowl of the Chamber of Deputies, and it is no surprise that these were chosen for the covers of newspapers, but the aestheticization of antidemocratic protest recalls the ominous label of sublime that someone gave to the orchestration of the 9-11 criminal attacks.

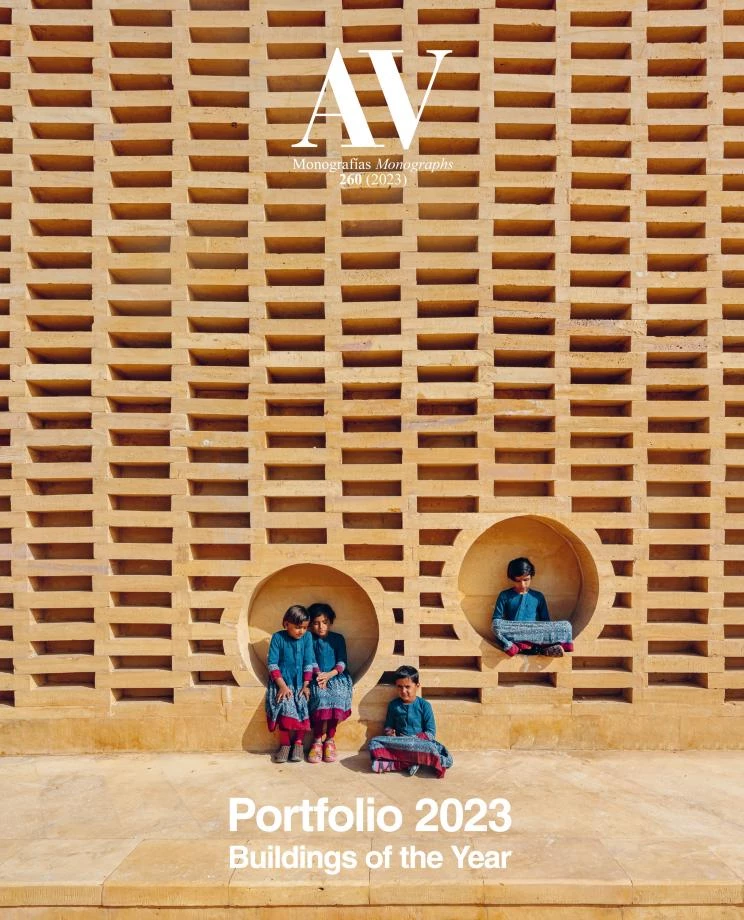

However, the perception of architectural works invaded by crowds has an appeal that contrasts with their frequent presentation as empty objects or spaces, frozen sculptures that barely show their role as stages for life. For instance, it was fascinating to see the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo, the masterpiece of João Vilanova Artigas and Carlos Cascadi, packed with students gathered in an assembly, and it was also enthralling to contemplate the image of the Casa del Fascio in Como, the best building by Giuseppe Terragni, as the backdrop of a mass listening to Mussolini announce through speakers Abyssinia’s annexation, and this in spite of the opposite ideological content of the two episodes, and in spite too of the known manipulation of the second photograph. Those crowds before eminent architectures are now only a historic testimony, but those on screens and covers today represent a social fracture and a cautionary warning about the fragility of democracies.