The Urban Rebellion of the Middle Classes

Spring.São Paulo and Istanbul have been the scene of urban revolts against the elites, and the protagonists were young people of the emerging middle classes.

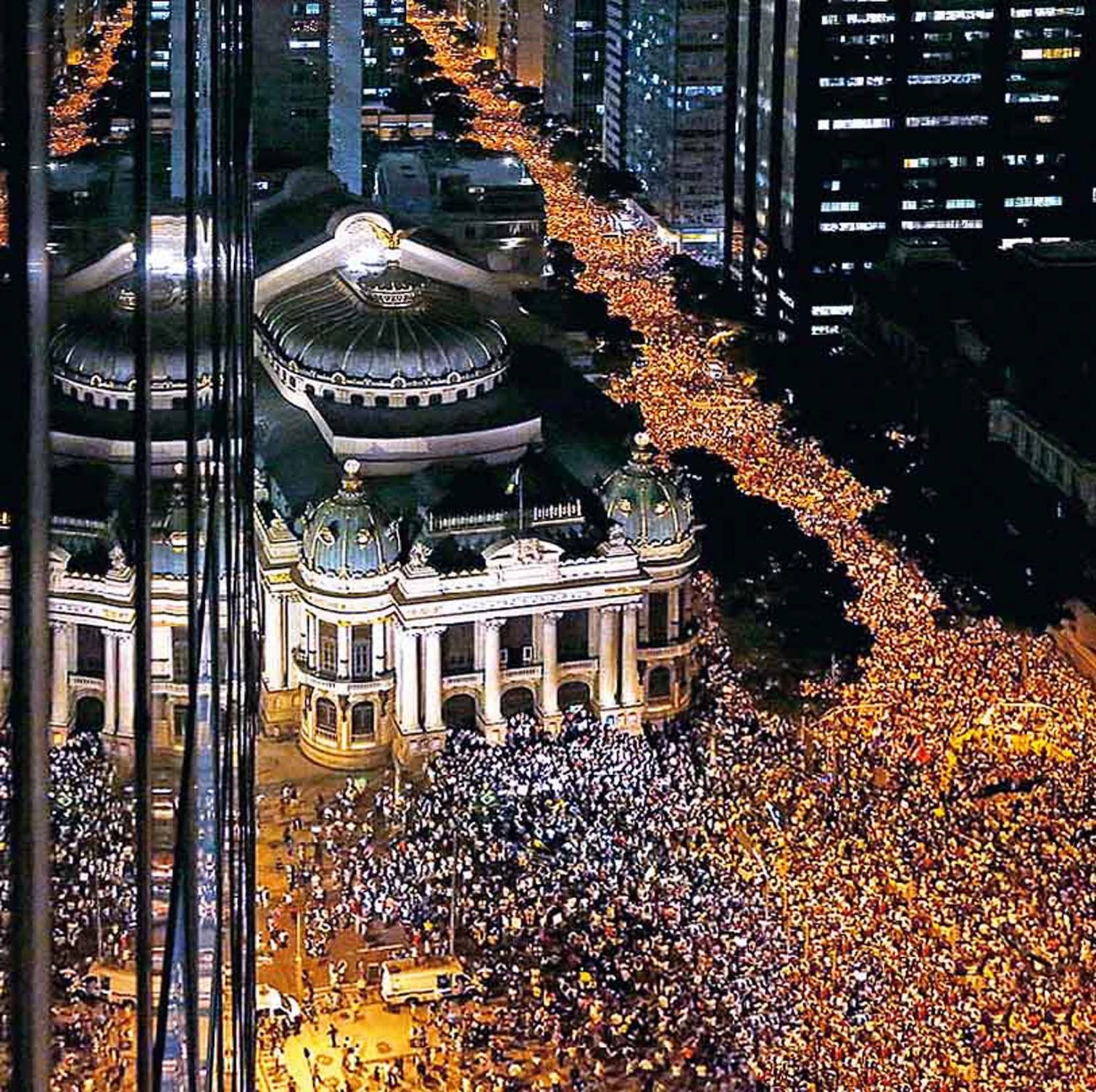

A specter haunts the world: the rebellion of the middle classes. In the latest episode, the cities of Brazil and Turkey have been the scene of an uprising against political and economic elites by young people summoned through social networks and provoked initially by an urban conflict: transport fares in São Paulo or the redevelopment of a park in Istanbul. Both cases involve countries with resilient democratic governments and robust emerging economies, so the protests cannot be attributed to absolute lack of freedom or the desperation of misery; they are rather revolts against authoritarianism or corrupt elites, as well as against growing social inequality and the erosion of the expectations of emerging middle classes. Matters of municipal administration – such as an increase of 0.20 reals (7 euro cents) in the price of a bus ticket or a license to build in the city center – have created disturbing political crises, throwing doubt on the legitimacy of the governments of Dilma Rousseff and Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose democratic origins must be constantly validated through the fair exercise of power. It is precisely this collission between the legitimacy of origin and the legitimacy of exercise that has just brought about the fall of Mohamed Mursi in Egypt.

In Brazil, soaring inflation and falling growth make it difficult to meet the social demands created by the economic boom of the last decade, and citizen frustration pounces on elite groups perceived as corrupt, while questioning the colossal cost of events like the FIFA World Cup, estimated at 10 billion euros, which in many of the championship venues will not even cover the promised transport infrastructures. And in Turkey, where the persistent Kurdish conflict and the Syrian war are a hindrance to its relationship with the Middle East and to its ambition to be a reference for the countries of the Arab Spring, the urban battle of Gezi Park and Taksim Square – with the population opposed to a project which is as legal as it is representative of the current real estate boom – has mobilized the middle classes against the regime’s authoritarian reflexes and confessional slant, whether by occupying the endangered park or through the silent, still presence of ‘standing men’ on Taksim Square; a dramatic action initiated by choreographer Erdem Gündüz.

The increase in the price of a bus ticket in São Paulo or the plans to build inside a park in Istanbul sparked popular protests in Brazil and Turkey, questioning the political legitimacy of the regimes in both countries.

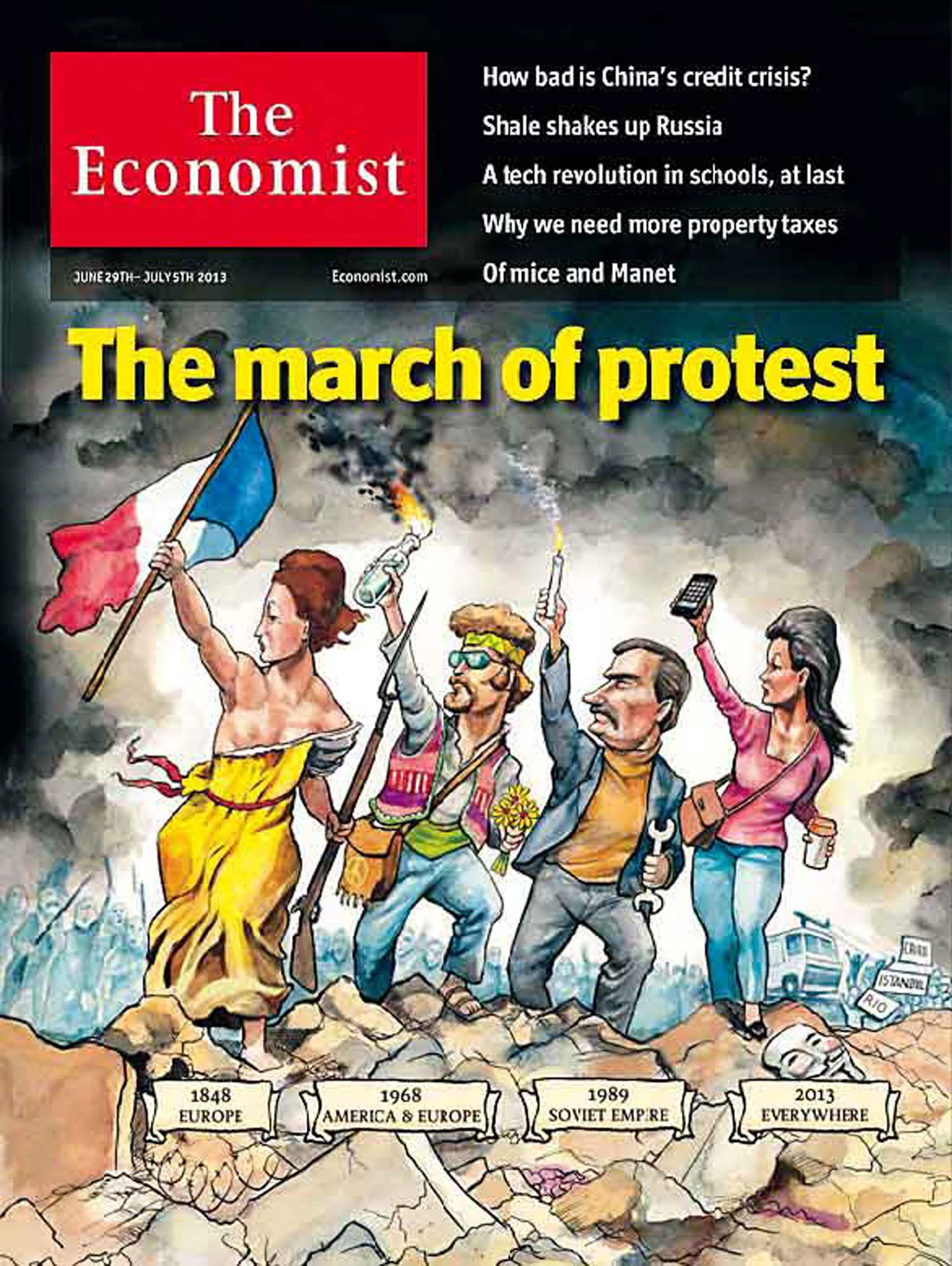

Sharing the peaceful, festive nature of ‘indignado’ rallies in Europe and America, and in the wake of other protest movements that have of late shaken the world, from Indonesia or India to Bulgaria or Israel – and these days tragically in Egypt –, the simultaneous uprisings in Brasil and Turkey have made journalists like David Rohde write in The Atlantic on ‘The Revolt of the Global Middle Class’ and magazines like The Economist produce cover stories on ‘The March of Protest,’ judging 2013 as a historic milestone comparable to those of 1968 and 1989, the cultural revolutions of the youth insurrections and the ‘negotiated revolutions’ provoked by the end of the Cold War. As for the current revolts, many analysts point out two features: on the one hand a better understanding of the nature of power by the young people who lead them, and on the other a more efficient use of new communication technologies. But other analysts stress the ephemeral character of mobilizations averse to stable organization, hostile to political parties, and preferring protest to the exercise of parliamentary opposition; also pointing out the ambiguous nature of social networks and communication tools, which serve as much to disseminate incriminating videos and coordinate rallies as to identify protesters through control of mobile phones or face recognition technology.

Brazil and Turkey are laboratories of digital protest, theaters of a mass clamor for better urban life, and perhaps also examples of the rebellion of the new middle classes against ‘extractive elites.’ Those who coined the term, the Turkish economist Daron Acemoglu and the American political scientist James Robinson, doubt that the democratic demands being made in Brazil and Turkey are results of the economic boom experienced by both countries, skeptical as they are of the modernization theory formulated by Martin Seymour Lipset, which automatically connects democracy to prosperity. In the opinion of the MIT and Harvard professors (who also question the alleged protagonism of the middle class in political change, emphasizing the importance of the mobilizations of the marginalized and the excluded), democracy is to a large extent independent of prosperity and finds less stimulus in boom than in bust. If they are right, Spain’s current economic crisis could well carry the seed of political regeneration: the way things are now, this would not be the worst outcome.