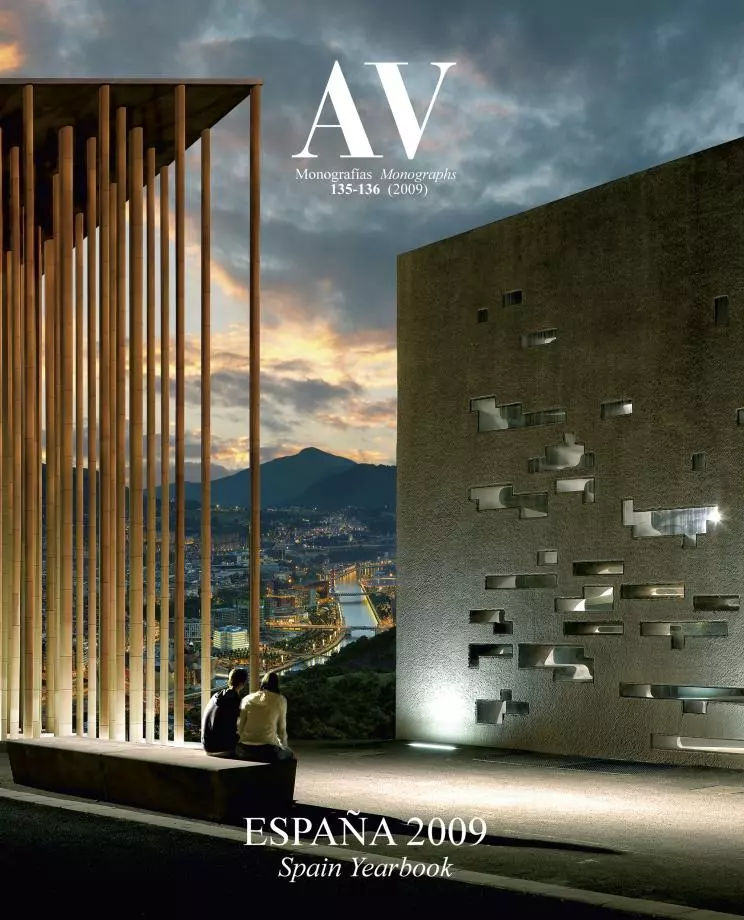

The Best and the Worst

The arrival of the most prominent world architects in Olympic Beijing has raised questions about the authoritarian character of the Chinese regime.

Why do the best architects build for the worst regimes? This is the question that Richard Lacayo raises in Foreign Policy. Illustrating his article with works of Norman Foster and Rem Kool-haas in Russia and China, the critic of Time magazine brings to a rhetorical paroxysm the climate of opinion that has become widespread in the West on the eve of the Beijing Olympics. In his censure he also includes the emirates of the Persian Gulf –where a good part of the international elite, from Frank Gehry to Jean Nouvel, is building skyscrapers or museums – and ex-Soviet republics like Kazakhstan, whose leader, Nursultan Nazarbayev, has adopted Foster as his leading architect, or Azerbaijan, where Zaha Hadid is to build a cultural center named after Heydar Aliyev, an old KGB member who governed the country up to his death, and at whose tomb the Iraq-born architect laid flowers; occasionally, one or another of the texts that have sparked this controversy mentions the works that Oscar Niemeyer carried out for Hugo Chávez or Fidel Castro, and even the project for a presidential library that was commissioned to Robert Stern by George W. Bush; and almost all bring up the affairs that masters like Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier had with totalitarianism in the period between the wars. Nevertheless, the spool and the guiding thread of this crop of critical texts are, inevitably, China and the Olympics.

The heavy shadow of totalitarianism was cast over works as light as the ‘water cube’, the bubbly pools designed by PTW.

China, a Whirlwind of Bad Press

From Robin Pogrebin in The New York Times to Roman Hollestein in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, the debate on architects who work for despots or totalitarian states has been in tune with the polemic Olympic torch relay, the wave of protests generated by the Tibet conflict and the numerous reports on the state of human rights in the country: China is guilty of the persecution of Christians or the Falun Gong sect, of censorship in the media or the web, of the marginalization of political or cultural dissidents, and even of the Darfur killings, execut-ed in complicity with its ally, the Sudan government, in the context of what The Economist calls Chinese ‘new colonialism’ in Africa and Latin America. From Hollywood, which nourished the current atmosphere of rejection with Spielberg’s refusal to organize the opening ceremony, to Amnesty International, which puts China on the cover of its an-nual report, the entire symbolic conglomerate has turned its back on a country whose spectacular eco-nomic success is attributed to a predatory model that devastates the territory with works like the Three Gorges Dam (with the forced relocation of millions of people), destroys cities with uncon-trolled development, and increases global warming with the mushrooming of coal-fired power plants, heavy industry, highways and airports, bringing pollution to such levels that some elite athletes have threatened to boycott the Games.

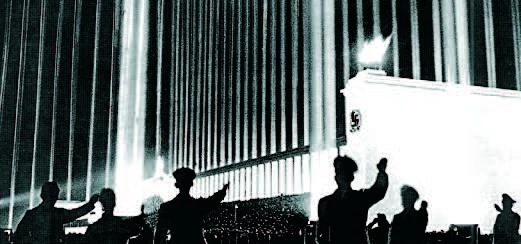

Evoking the colossal scenographies of Nazi Germany, the Western media sparked a debate on the participation of star architects in iconic works of Olympic Beijing such as the ‘bird’s nest’, the stadium by H&deM.

In this whirwind of bad press, where almost the only thing we have yet to accuse the Chinese of might be of increasing the protein content of their diet – thereby shooting up world food prices –, little attention has gone to their exemplary reaction to the Sichuan earthquake, in contrast to the Myanmar Council’s management of the recent cyclone, or even to the US Federal Government’s dealing with the hurricane Katrina; nor has there even been sufficient emphasis on how China’s extraordinary efficiency is based on the Confucian values of hierarchy, discipline and industriousness that in the West are considered obsolete. The grasshopper condemns the ant but, as the film director Wong Karwai points out: “it is easier to demonize China than it is to understand it”. This has been very well understood by the philosopher Slavoj Zizek, who in a recent article about the Tibet crisis, published in Le Monde Diplomatique, drew attention to the theocratic nature of the Dalai Lama’s brand of Bud-dhism, which is hard to reconcile with the hedonist New Age spirituality that is now becoming the dom-inant ideology, and which has an idealized Tibet for reference. As for China, the key question is not so much when it will adopt democracy as the natural partner of capitalism, but whether its authoritarian model will in the long run prove more efficient than liberal capitalism. David Brooks answered this question in the NYT by arguing that Chinese corporate meritocracy, based on subordination and effort, can be useful in raising a manufacturing econ-omy, but lacks the flexibility needed to generate the innovation that the information society requires

Beijing, the Iconic Works

It might be these limitations on creativity – the reason why so many Chinese artists, writers and filmmakers live outside the country – that have led China’s leaders to hire such a large number of foreign architects for the iconic works of Olympic Beijing. Among them are many of the world’s best, who have taken advantage of the exceptional circumstances of the commissions and the political support of a highly hierarchized society to build mem-orable projects: the airport of the British Norman Foster, a weightless golden dragon that is the world’s largest construction, the stadium of the Swiss partners Herzog & de Meuron, a titanic nest of steel that has become the emblem of the Games, or the CCTV building of the Dutch team OMA, a skyscraper shaped like a leaning folded door, are works that will form part of the history of architecture and the history of China.

Tanto el estadio olímpico de H&deM como la sede de la CCTV diseñada por OMA se construyeron con el concurso de un ejército colosal de operarios, que a menudo trabajaron en condiciones de extrema singularidad y dificultad.

But can it be said that the best are building for the worst? Would these projects have been possible without the economic boom, the desire for affirma-tion and the staunch support of a society and a regime? Is the Chinese system detrimental to its cit-izens? Is China an irresponsible member of the international community? In his recently published book What Does China Think?, Mark Leonard has documented the rise of a new Chinese intelligentsia, grouped in a wide variety of research centers and think tanks in open competition with one another, which entails a clear challenge to the hegemony of the Western liberal model. To declare that ‘China is guilty’ is to avoid facing the reality of a country that is culminating a colossal peaceful revolution. And what if the best were building for the best?