Innocence Geometry

Four Japanese Architects

Kengo Kuma, Oribe Tea House, Gifu (Japan)

The bomb on Hiroshima caused not only trauma and radiation. It also had the paradoxical effect of opening up Japanese culture and society to the West. With the bomb came the Americans, and with them the artefacts of an incipient pop culture, plus the motifs of the architecture of Le Corbusier and the CIAM congresses, which in no time were assimilated into the first Japanese building considered ‘modern,’ thought of as a tribute to the destructive but simultaneously transformative power of the uranium bomb: the Hiroshima Peace Center and Memorial Park, a work of Kenzo Tange.

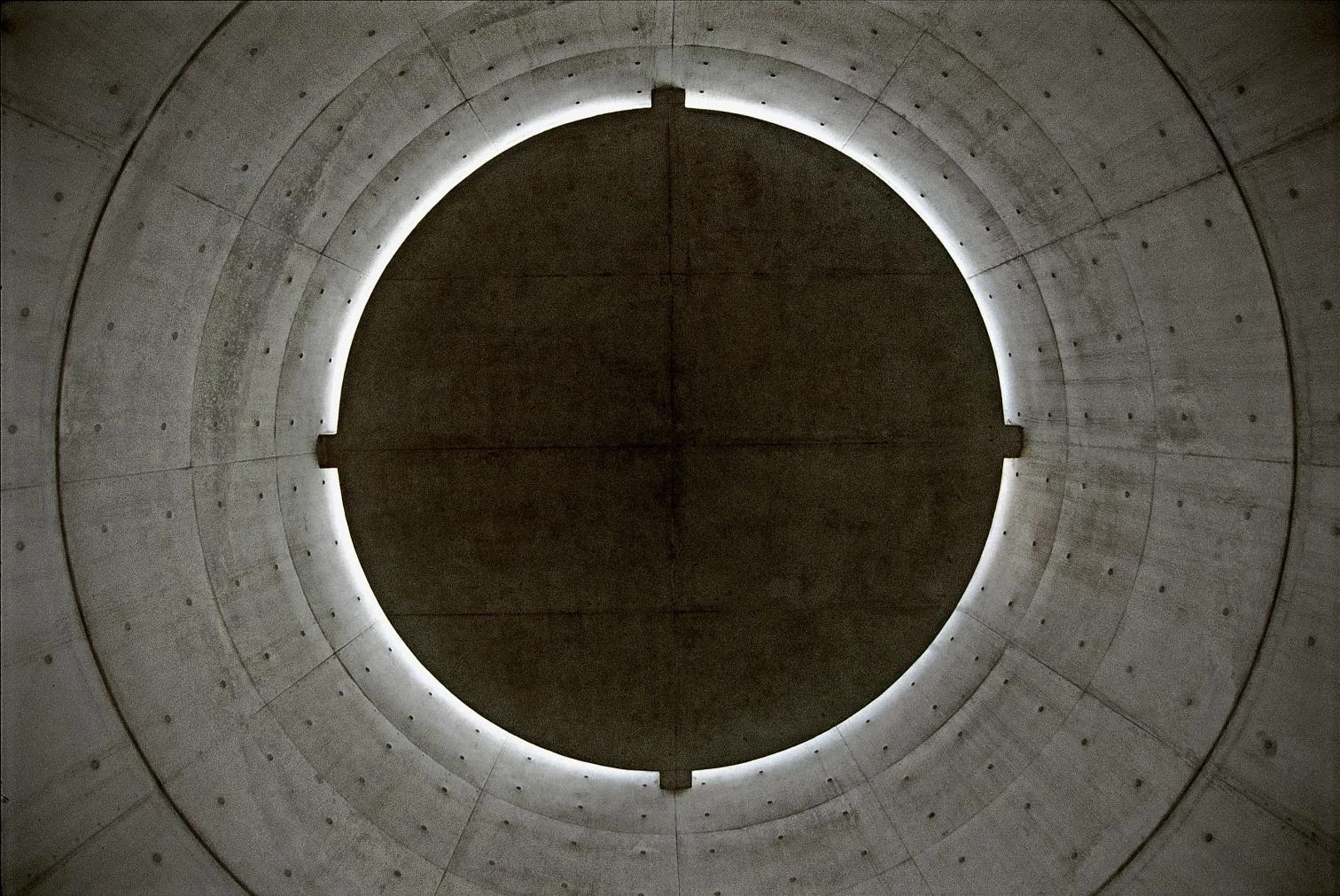

The memorial drinks from the béton brut aesthetic and from functionalist dogmas, but without evoking the country’s history any less. And this genealogical cooperation became the stamp of an architecture which over the past seventy years has ceaselessly been marked by the dialogue between cosmopolitan openness and attachment to the constants of tradition: the same interaction that equally explains Tange’s solemn expressivity and Kikutange’s metabolist follies, Ando’s material poetic and Ito’s nomadic experimentation, and SANAA’s vibrant bareness and Ishigami or Fujimoto’s games of geometry, so close to the art installation.

Such games, precisely, are among the motifs of the most recent crop of Japanese architecture, which in the combination of essential figures – sometimes Cartesian, other times organic – has found a field of experimentation where attention to the rigor of rules is combined with innocence of the kind with which children partake in any play activity. If Wright (and after him the architects of the historical avant-garde) acknowledged the combinatory logic of Fröbel’s building sets as one of the forces lying latent in his design processes, today’s Japanese architects – influenced perhaps by the dreamlike spaces that abound on their digital screens – do not look for inspiration in games as much as they transform their works into games whose laws can be unraveled.

This dossier presents the logic through four works by Japanese architects, three located at home and one abroad. While the Zaishui Art Museum in Rizhao (China), by Junya Ishigami+Associates, offers a take on the nautical themes of modernity by means of a 1000-meter-long building that sinks into an artificial lake, the Ishinomaki Cultural Center by Sou Fujimoto Architects plays with the city’s childlike imagery through houses with dual-pitched roofs and a chimney. For its part, the Yashima Mountaintop Park in Takamatsu by SUO and Style-A indulges in sinuous forms that interweave with the landscape, and the Culvert Guesthouse in Miyota by Nendo uses pieces taken from sanitation infrastructures, reinterpreting Fröbel’s educational toys on an emphatically minimalist note.

Tadao Ando, Meditation Space UNESCO, Paris (France)