Geographical Matter

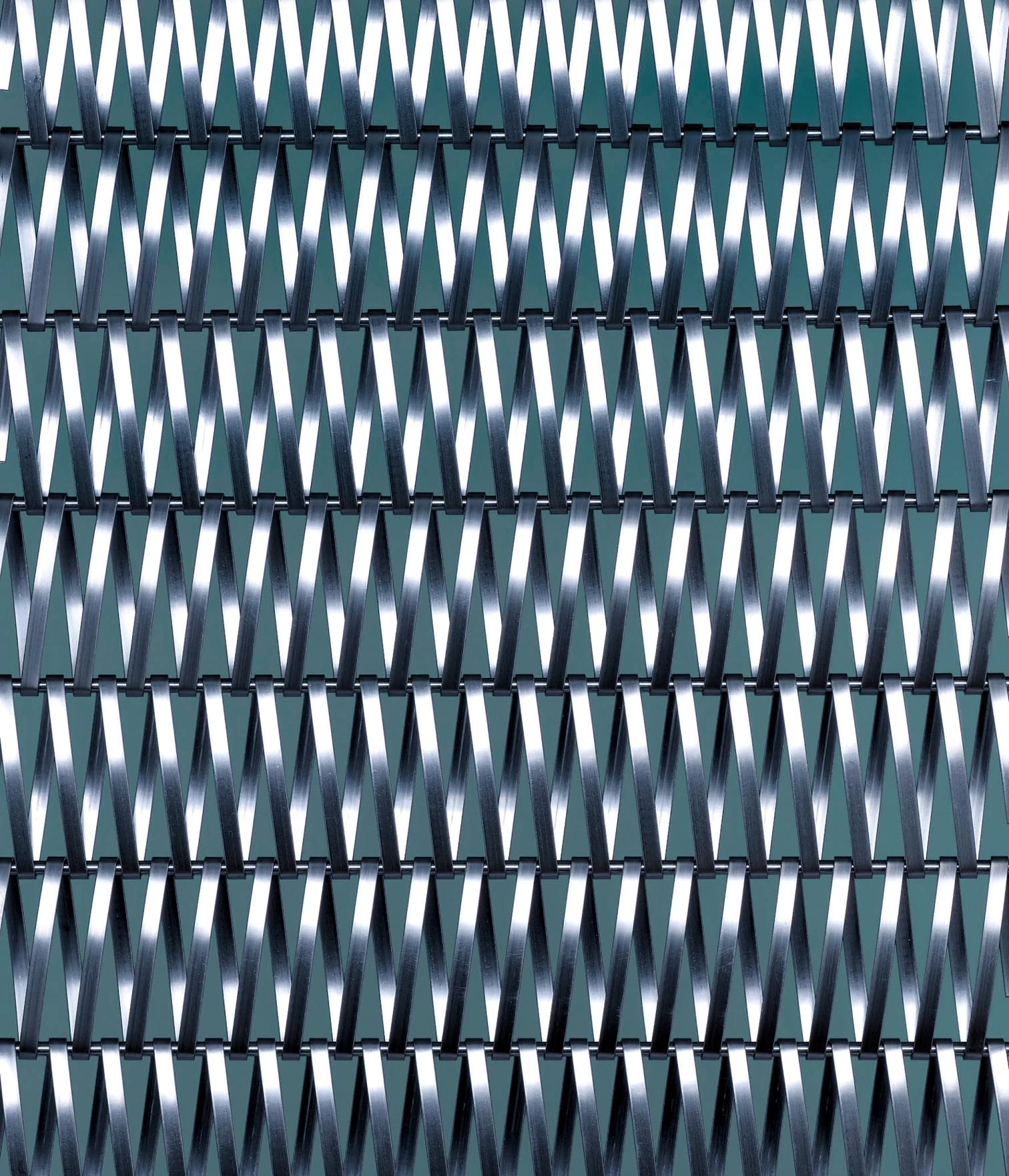

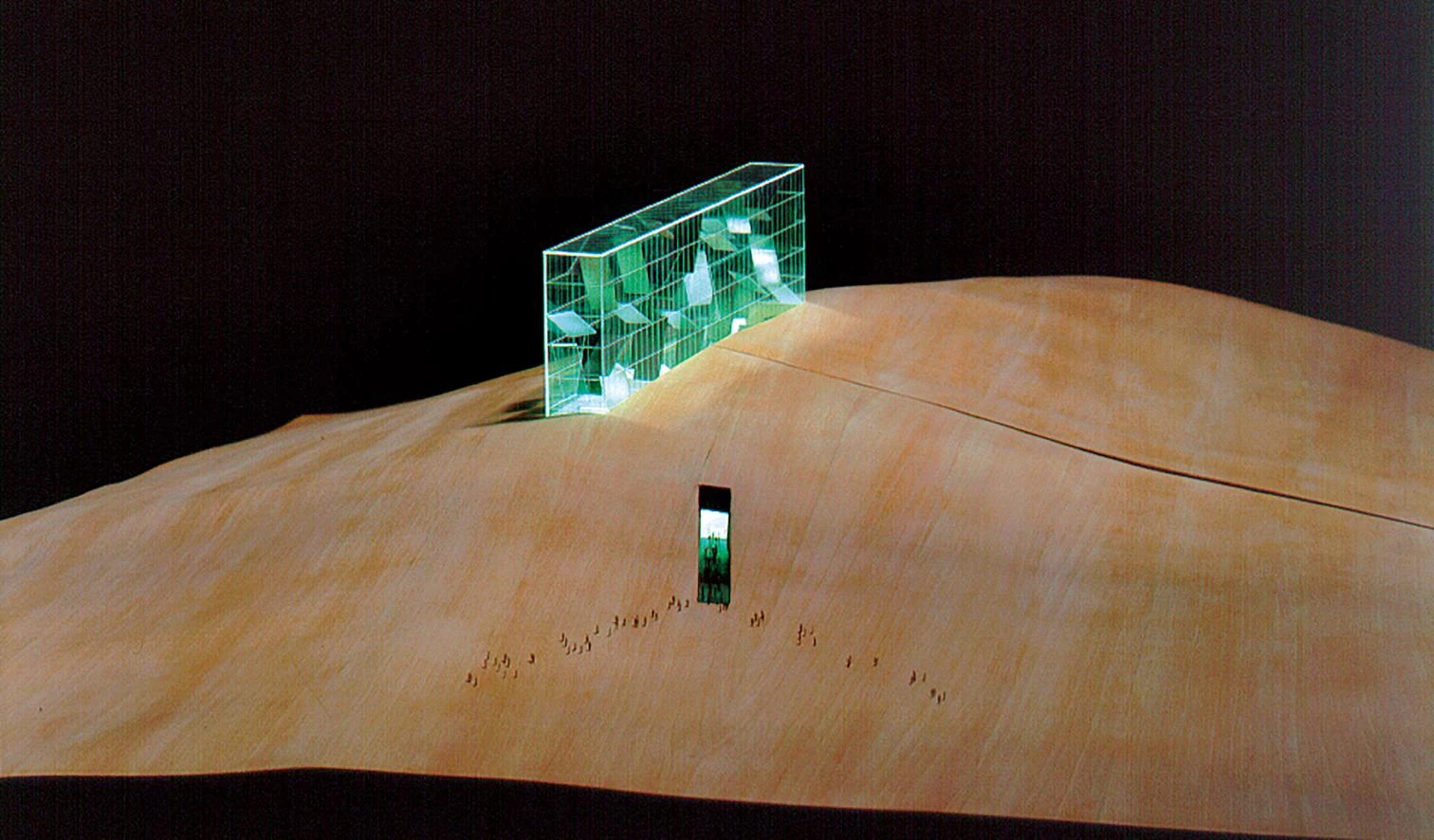

Dominique Perrault joins geometry and geography in a new architectural place, sparsely inhabited by families of hermetic objects, all built with exact logic, and which face the environment with metaphysical aplomb. Instead of seamlessly merging with the topographical curves, the volumes rise over the terrain or pierce it with the violent precision of the structure or the scalpel. More architecture of the territory than generic city – more Gregotti than Koolhaas –, these prisms of minimum expression and maximum discipline reach their selfabsorbed monumentality through scale, developing their discourse of disappearance through the absence of design or even contact, and offer the clean rigor of their extreme simplicity as a neutral background for social choreographies.

Classical buildings after all, carried out in intimate dialogue with industry and self-referential in the careful syntax of details, the material results of the Perrault method achieve a unique independence from the urban and natural context, but also from the ups and downs of their time, justifying their condition of being geography without history, and attaining at once the rare privilege of timeless appearance. Since leaving behind every postmodern temptation with the Hôtel Berlier of 1986, and up to the last five years, when his projects begin to explore more sculptural paths – perhaps in the wake of the non nata series of wrapped stacks initiated at Tenerife’s Playa de las Teresitas –, at least two decades of the architect’s career can be duly described in these concise terms.

This transition from abstraction to gesture – nuanced by the survival of material inventiveness and sensibility towards landscape, but also by the guiding thread of artistic action, that links many episodes of his oeuvre – is clear in the sequence of competitions carried out by Perrault in Spain during the last ten years, from the City of Culture of Galicia or the Reina Sofía Museum in 1999 to the most recent project entries for Soria or Granada. Competitions some of them lost, and others won like the Tenerife project – later sadly cancelled –, the Léon Congress Center – whose construction is due to begin this year –, or the very successfully completed Magic Box in Madrid, the colossal indoor facility for tennis that is also the symbol of the olympic vie of Spain’s capital.

In all of these competitions in our country – setting aside the changes in strategy or the degree of success of the proposals –, Perrault has always shown a will to take concepts to an extreme, an approach that urges him to undertake each occasion as a double or nothing bet. This impassioned and essentially artistic audacity, that makes him play always on the offensive, scorning the lukewarm compromise of the draw – and which he has also shown when on juries like those of the Mies Award or the Ciudad del Flamenco –, is perhaps behind the last crop of projects, where the confident consistency of his prisms and cuts is replaced with a flurry of impatient forms, testing the skill of the builder with the artistic drive beating beneath his geographical matter.

Luis Fernández-Galiano