León in the sun

The nearly two-thousand-year-old León is rejuvenated with new works and projects, from the iconic MUSAC to the recently judged Trade Fair and Congress Center.

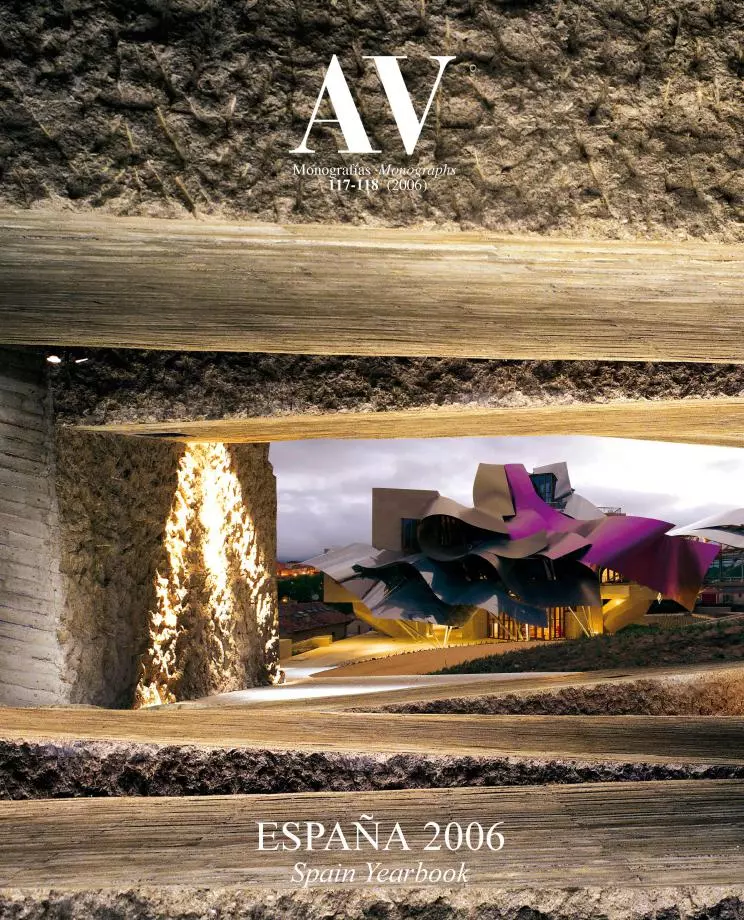

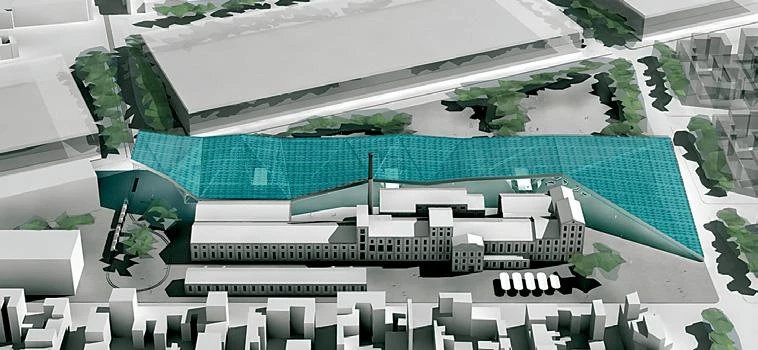

The people of León claim to bask in the sun. Against the frozen image of the Castilian-Leonese winter, the inhabitants of the city founded by the 7th Roman Legion remind the visitor that it is among the Spanish capitals that boast the most hours of sunshine per year. This climatic fact has much to do with Dominque Perrault’s success in the recent competition for the Trade Fair and Congress Center on the spot of the old Santa Elvira sugar plant. Across the future bullet train station, and flanking character-less, preexisting industrial buildings where he plans to put the convention rooms, the French architect arranges the trade fair grounds beneath a colossal photovoltaic and translucent roof that folds weightlessly over the premises, and stretches above the street with a spectacular canopy that serves to announce the center’s presence along the urban axis that, over the railway tracks and the Bernesga River, connects an up to now marginal area to the cathedral and the old quarter. This ‘solar’ precinct, whose huge crystal captures both clean energy and the generous subsidies allocated to renewable sources, and which with the hustle and bustle of conventions will light up anew the impressive and abandoned spaces of the dead factory, won over ten other projects in an international competition where most of the foreign teams were a disappointment.

Dominique Perrault’s project for the new Trade Fair and Congress Center stretches a photovoltaic and translucent roof over the buildings of an old sugar mill, heralding its urban presence with a monumental canopy.

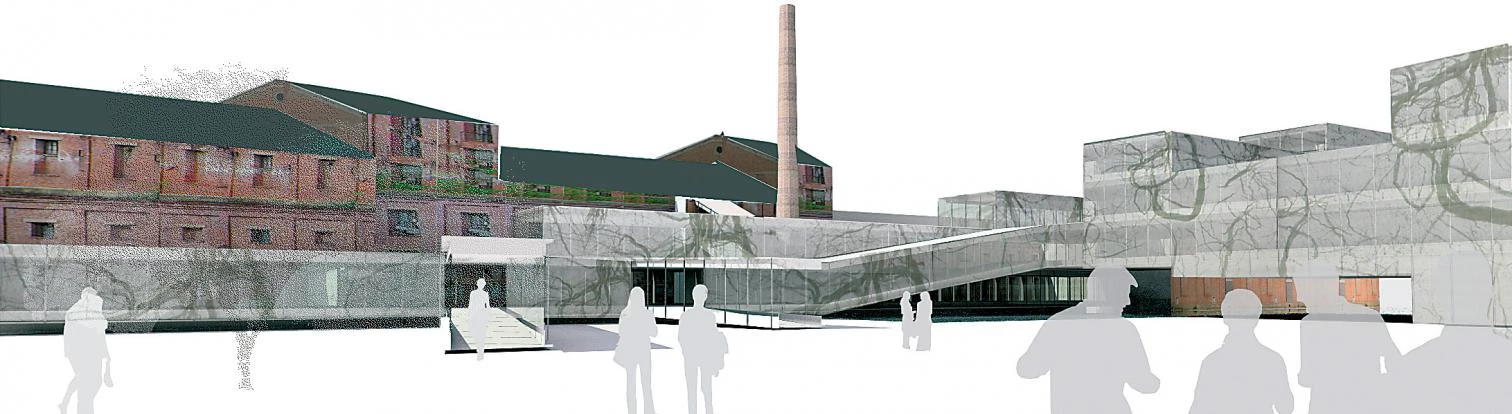

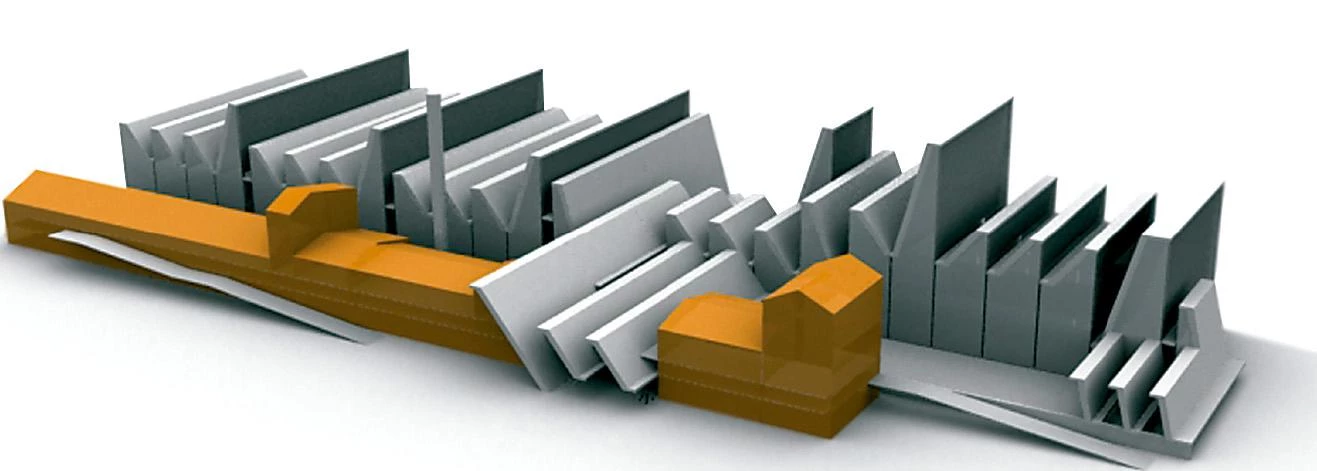

Although the grand prize, after an articulate, eloquent presentation, went to the author of the Grand Bibliothèque of Paris and the Caja Mágica of Madrid, the other awards were given to Spanish studios. The first runner-up was Francisco Mangado, recent winner of the competition for the Congress Center of Palma de Mallorca, who in this case defended a sober and pragmatic proposal, a project based on one hand on adapting the factory’s brick-and-steel sheds to trade fair uses, and on the other hand on a series of convention rooms of new construction that are livened up by footbridges evoking the random order of industrial complexes: a different interpretation of a familiar program for the Navarrese, who in the wake of the Baluarte of Pamplona has the convention centers of Ávila and Palencia under construction, the latter also in an old factory, and who, incidentally, is competing with Perrault, Chipperfield, and three engineering firms for the construction of the nearby station that will bring the bullet train into León. The third prize was shared by two Madrid partnerships: on one hand, Fuensanta Nieto & Enrique Sobejano – authors of the Congress Center of Mérida and winners, just two weeks earlier, of the Convention Center that will be inside the Expo 2008 premises in Zaragoza –, who presented a sculpturally forceful project with a serrated profile that extrudes to form a volume crowned by rows of giant skylights; on the other, Iñaki Ábalos & Juan Herreros – their work currently on display in Madrid–, who formulated a rigorous, rough proposal based on the expansive nature of trade fair programs, and gradually occupied the whole site with a checkerboard of roofs inspired by those of their own sewage treatment plants.

In the competition for the Trade Fair and Congress Center prizes went to the sober proposal livened up by footbridges of Mangado, the huge sawtooth skylights of Nieto & Sobejano and the extendable checkered roofs of Ábalos & Herreros.

The two consolation prizes fell upon projects of other Spanish firms: on one hand, the team led by Andrés Perea, who with a group of brilliant young collaborators presented a utopian and generic ‘umbrella building’ proposal, that with computer tools pushed to the limit the sixties obsession with the isotropic space created by a horizontal roof where structure and services are integrated; and on the other hand, the partnership of Ricardo Aroca & Fernando de Andrés, who proposed inserting the complex in the urban structure with great pedagogical intelligence, and with special sensitivity to the city’s historical evolution and to the aesthetic emotion that provokes the turbulent beauty of the industrial ruins. More disappointing were the three projects drawn up from London, none of which were finally presented by their authors: Alejandro Zaera & Farshid Moussavi’s ceramic, polychrome canopies, David Chipperfield’s still-life of free-standing pieces, and Zaha Hadid’s warped mollusk, – incidentally the only proposal that dispensed with every one of the existing factory structures –, all failed to convince the competition judges of their virtues. Neither did the cheerful entry of Eugenio Aguinaga & Ricardo Legorreta, despite the elegant charm of the veteran Mexican architect, nor the very simple, elementary idea of Carlos Ferrater & Juan Trias de Bes, which the latter presented with little conviction.

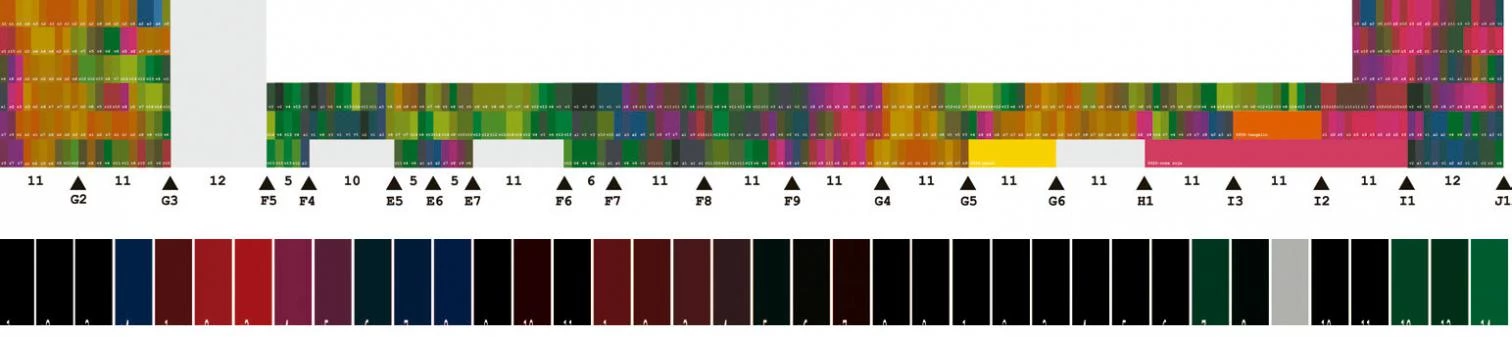

Shortly after its opening, the MUSAC by Mansilla & Tuñón – that pixellates a stained glass window of the cathedral to build a colorful facade –, has become a referent of the art scene and a symbol of the current urban renewal..

The jury gathered in the Auditorium of León, a refined, urbane work of Luis Moreno Mansilla & Emilio Tuñón that theatrically closes the civic space formed by the facade of the Hostal de San Marcos with a screen of syncopated rhythms and Corbusian flavor, and which engages in courteous dialogue with its neighbors to accommodate a concert hall of dark wood, warm and intimate like a ship’s hold, whose clear velvet acoustics we could hear praised by the tenor Jaume Aragall. These same Madrid architects are the authors of another León building, the splendid MUSAC, a museum of contemporary art, where their contextual language becomes structuralist so that it is a geometrical grid of squares and lozenges that generates the plan, whose perimeter is finally shaped more in accordance with its internal law than with the insipid urban environment. All this in what amounts to a critical revival of the Dutch experience of four decades ago, ornamented and monumentalized here by the grand chromatic gesture of the facade (where a titanic pixellation reproduces a fragment of the cathedral’s oldest stained glass window), now no less than a logo of the new and exemplary art institution it houses. Mario Vargas Llosa recently praised the cosmopolitan climate of the Berlin that now exhibits the extraordinary Shirin Neshat. He might have added that the best current exhibition of the film director and photographer is, precisely, in Leon’s MUSAC. At the Hostal de San Marcos we came across the lucid and unsociable Michel Houellebecq, who had come out of his reclusion in Almería to accept an award in León. The implausible coming together of the Iranian artist and the French writer leads us to think of how this city is able to reconcile cultural universes as antithetical as the paths of its two most conspicuous politicians, the conservative Rodolfo Martín Villa and the socialist José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero: polychromatic mysteries of the sun that shatters in the stained glass windows of León.