Artificial Gas

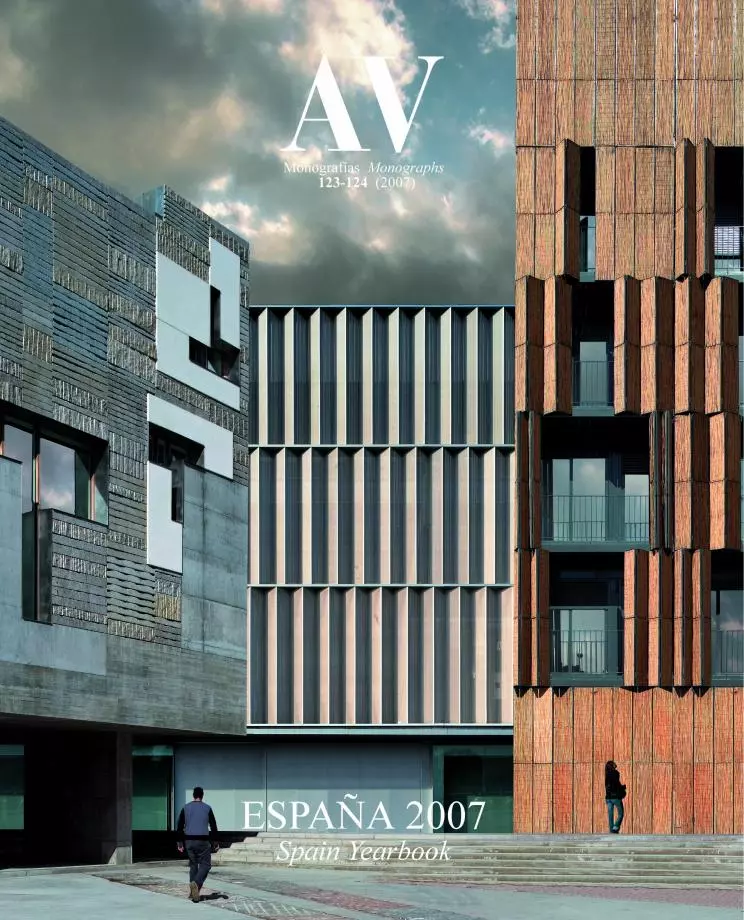

The Gas Natural building, conceived by Miralles, holds up its shaken forms as an urban landmark, a symbol of power and a sign of troubled times.

Rather dead than plain: the headquarters of Gas Natural is a provocatively affected work, what with its random interlockings, implausible projections, and decomposed volumes. Everything about it is forced and excessive, with that mood of irresponsibility that characterizes a cartoon and the playful origami that comes to a peak in an inane corbel molded with folds of glass. The sculptural lyricism of Enric Miralles, who in other posthumous works like the Scottish Parliament or the Santa Caterina market has produced amazing fruits, be-comes sadly arbitrary here, while the calligraphic violence of his drawings seems to be domesticated by the conventional vulgarity of a curtain wall that is barely nuanced by variable fragmentation and random coloring. The building turns out to be an accidental headquarters because its true function is to be an urban landmark, raising its teetering forms over the broad landscape of the Barceloneta quarter, while expressing the transition from the old gas plant’s material and structural clarity to the immaterial and mediatic argument of our own postindustrial times.

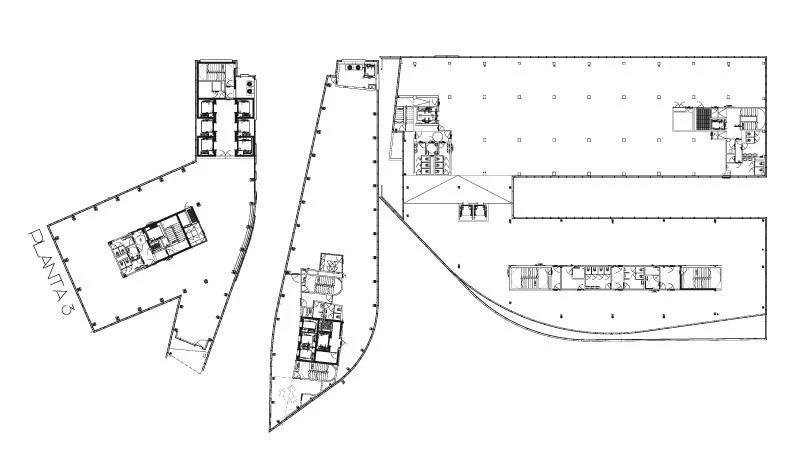

The prematurely deceased Catalan architect left a handful of remarkable works – which are all the more brilliant when most topographical – because his bright choreographies required making dance steps on a territory shaken by the forces of context, and this is perhaps why many judge the dreamlike orography of the Igualada cemetery, where he is buried, as the project where his language of gestures comes forth most eloquently and movingly. In the Barceloneta, however, the effort to bring together adjoining urban tensions in a sculptural piece that crystallizes fluxes with its quiet movement is contradicted first by its vertical formation, which does not manage to connect with the lower volumes in a coherent whole but rather makes the cantilevers mere athletic anecdotes, and second by its vitreous lightness, which abstracts the building from the solidness of ground without which the gym-nastic gravitas of Miralles’s finest moments cannot easily come true. Enric may have had his head in the clouds, but his architecture was great as long as he had his feet firm on the ground.

Opposite the Ciudadela Park, on the grounds of the old gas factory, the building stands out amid the landscape of the city as a symbolic object that marks the territory in the same way as the towers of the Sagrada Familia.

It is probable that in the same way that Barça is more than a soccer club, Gas Natural is more than an energy company. After all, it is one of the Caixa’s industrial jewels, formed by the merger of Catalana de Gas and Gas Madrid, and surely this symbolic circumstance had something to do with the decision to build a unique headquarters, one where corporate needs are subordinated to artistic expression and its role as urban landmark. But we have to resist the temptation to associate Miralles’s dynamic, unstable aesthetic to a Catalanism that would quickly have moved from the seny to the rauxa, as so many recent episodes of the once-upon-a-time ‘oasis’ suggests, from the ill-fated Gas Natural takeover bid on Endesa to the most absurd vicissitudes of Maragall’s tripartite government, from the stunned trip to meet with ETA in France to the soul-searching drafting of the Statute, and through the climate of political intimidation and street violence that has prevailed of late, presenting a distorted image of Catalonia. The disconcerting volumes of Gas Natural should not be the emblem of these troubled times, because the touch of surreal madness that characterizes this land must end up being absorbed by its civil culture of pacts and good sense.

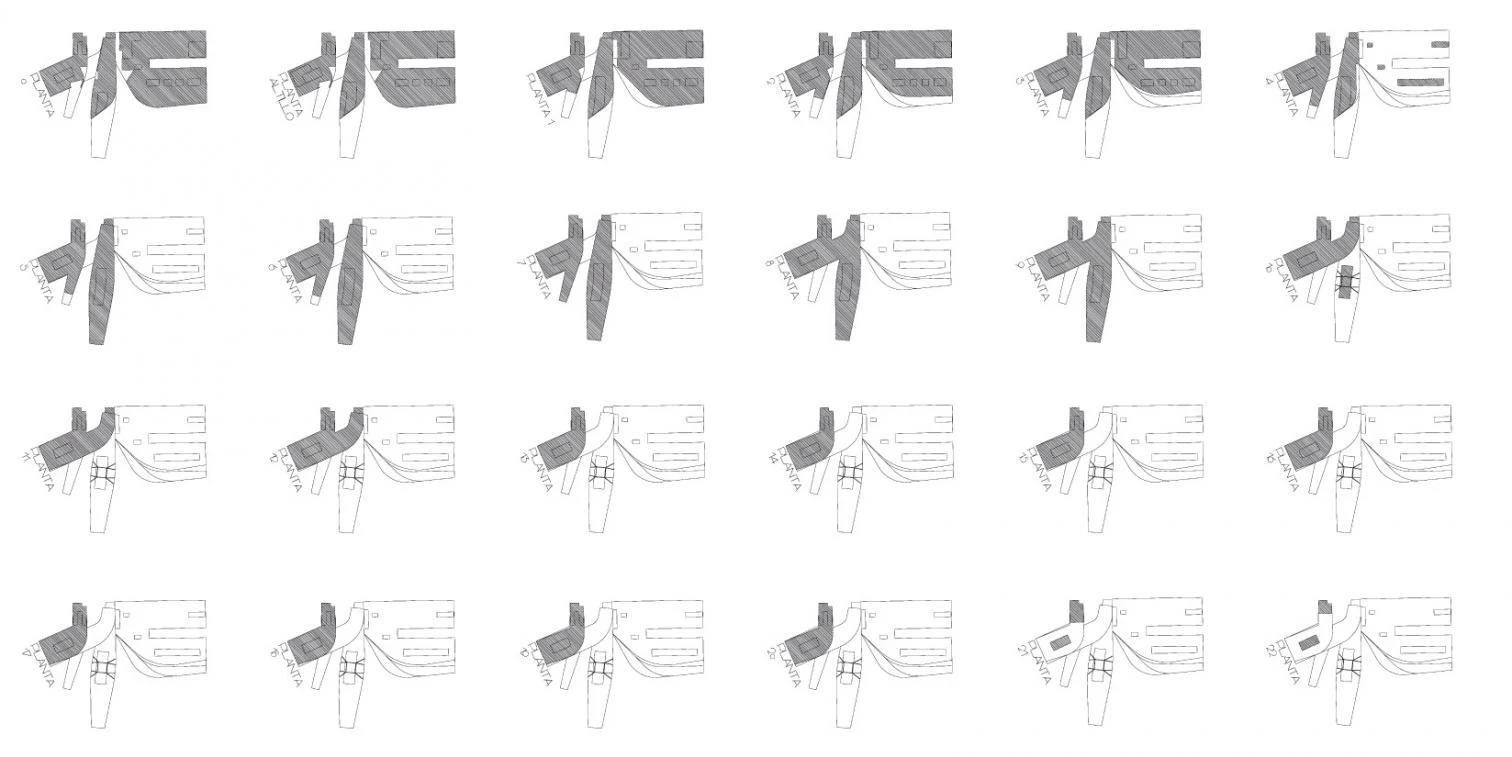

The offices of this firm’s headquarters are housed in sculptural volumes, interlocked in space and extended with cantilevers, endowing the company with a bold corporate image, at once fractured, shaken and dynamic.

Of course the strident polarization of Madrid’s politicians and journalists does not help to alleviate the stormy atmosphere of a Catalan scenario that has slid from its famous calm to the urban guerrilla of okupas that forces to cancel a summit meeting of European ministers or the torch parades that are more evocative of the totalitarian aesthetics of the 1930s than they are of the country’s Gothic roots. But Catalonia (and the Caixa that proudly displays its economic muscle with the Gas Natural building) has more to win with a ‘soft power’ in the Joseph Nye manner, woven with seduction, emulation, and example, than with abrasive confrontations reminiscent of the long gone social panorama of a bomb-ridden Barcelona once known as rosa de fuego.

Exactly a year ago, during the fishermen’s blockade of the main Mediterranean ports, the front page of El País showed a picture of Barcelona as seen from the sea. By doing this it inadvertently threw light on the new landmarks of the city’s profile, which turned out to be the corporate headquarters of two companies controlled by the Caixa, a savings bank that thereby affirms its central position in Catalonia’s social landscape. Both the Agbar shell and the Gas Natural sculptural tower rise over the low profile of the common city as assertive banners: emblems of economic power that do not even turn out to be too costly on the balance sheets of their owners. As the management of one of the Ibex companies disdainfully told the architect of its colossal Madrid headquarters: “In the end, the cost of the building is one billing day.”

The opening of the headquarters of a strategic energy firm ought to serve as pretext to think about the policy of national champions (Spain’s or Catalonia’s?), to discuss in detail the recent entry of construction companies in the sector of utilities (who knows if it is to prepare for the bursting of the real estate bubble by linking up with more stable enterprises, or to prevent foreign firms from coming into the picture), and to warn the public about the risks behind our growing dependence on imported energy (aggravated by the absence of a common European policy and inscribed within the menacing context of climate change). But our tribal conflicts prevent us from separating the urgent from the truly important, and a building that ought to be a model of energy saving and an example of civic responsibility, with the austere laconism that should be the mark of a company that must guarantee supply without being abusive in its prices, ends up being discussed as the failed artistic icon of an electoral and gaseous Catalonia. Mea culpa.