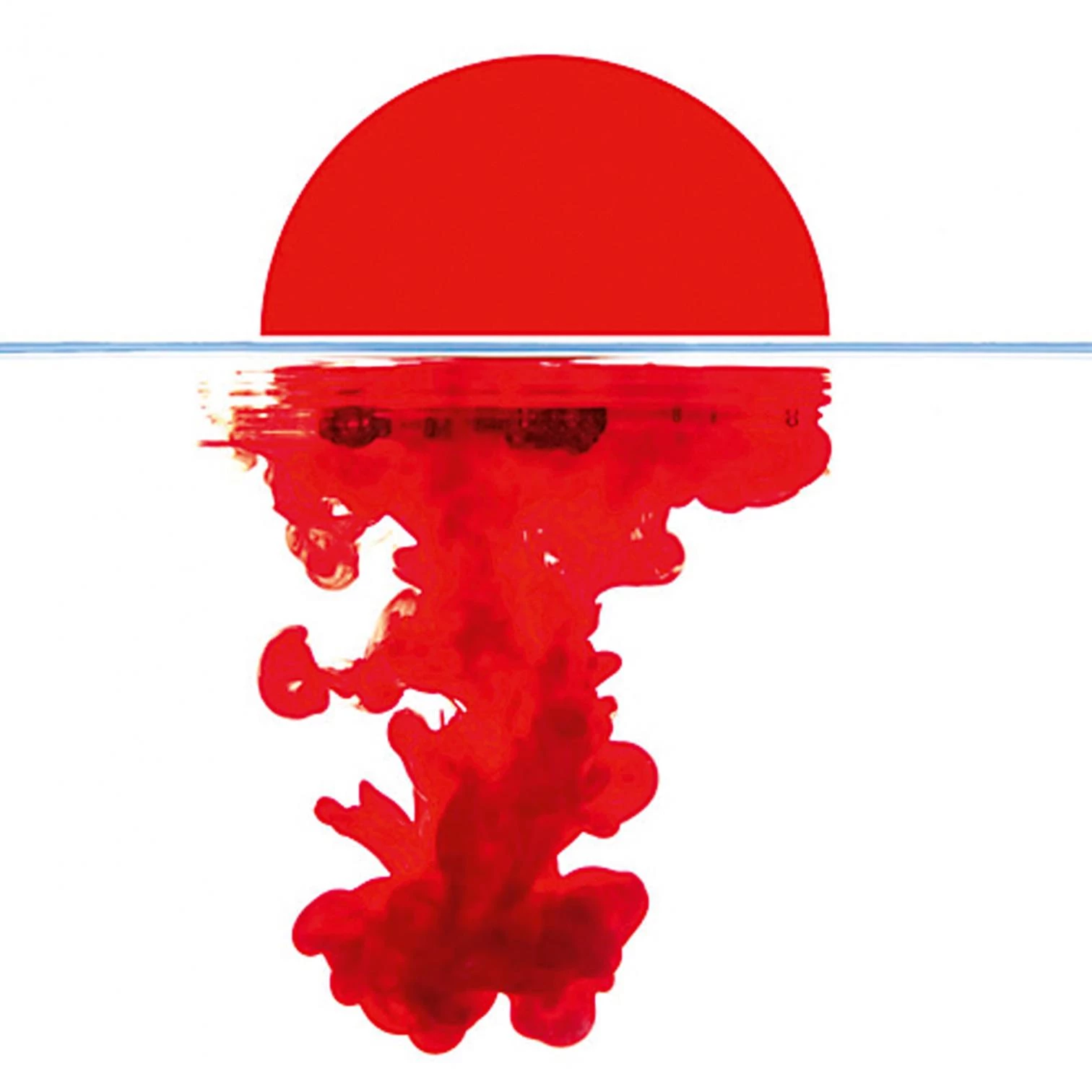

After each catastrophe, Japan reinvents itself. The design by the Israeli Yossi Lemel and the letter by the Swiss Daniel de Roulet are two answers to the tragedy of 11.3.11 whose common title, borrowed here, makes reference to the film by Alain de Resnais which was both a manifesto of the Nouvelle Vague and an exorcism of Hiroshima through an intimate dialogue about peace, memory and forgetting. In 1960, a year after the premiere of Hiroshima mon amour, Japan held the World Design Conference, where Kenzo Tange – who in 1950 had built the Hiroshima Peace Memorial as an emblem of democratic modernity – launched the Metabolist Movement, an architectural avant-garde to reinvent through technology a country defeated in World War II and constrained by a seismic, abrupt territory: a movement that the Dutch Rem Koolhaas, also coming from artificial landscapes, has revisited half a century later to rebuild through conversation the creative imagination of those pioneers, faced with mortality and forgetfulness.

During the three decades following the WoDeCo the country experienced an economic boom, witnessed by the world through the Tokyo Olympic Games of 1964 and the Osaka Expo of 1970, slowed down by the oil crises of 1974 and 1979, and that would reach its peak with the real estate and stock market bubble of the second half of the eighties. The bursting of the bubble in 1990 brought on a period of relative stagnation, which called for another architectural reinvention, this time around figures like Toyo Ito and, above all, his disciple Kazuyo Sejima, with works that pursue fluidity and lightness to represent the instability of the contemporary world. When AV explored the ‘Japanese Generations’ in 1991, the itinerary began with Tange and reached Ito, who in 1995 would win the competition to build his capolavoro, the Sendai Mediatheque, coinciding with another catastrophe, the Kobe earthquake, which fostered emergency architectures like those designed by Shigeru Ban, and that would forever mark the so-called ‘post-bubble generation’.

This generation would find in SANAA – established in the same year 1995 by Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa – its main reference. In 2004 I presided the jury that awarded them the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale; in 2005 Arquitectura Viva organized an exhibition in Tokyo in which SANAA became the most prominent participant; and in 2006 AV published a monograph to document a fascinating oeuvre that would receive the Pritzker Prize in 2010. But the 2011 tsunami, which devastated large areas of the country and brought the Fukushima plant to a stop, putting nuclear energy into question all over the world, has opened a new historical period for Japan, and prompted another reinvention of its architecture and its territory. This is the time for yet another generation, raised in the wake of SANAA but faced now with new challenges and risks. The Metabolists lived in the shadow of Hiroshima, but managed to raise the country’s architecture and self-esteem: no less is expected from the young who begin their career under the ominous shadow of Fukushima.