Window

The publishing house Siruela, which placed the philologist Irene Vallejo on the bestseller lists with her marvelous Papyrus: The Invention of Books in the Ancient World (a work based on her dissertation, which also brought her Spain’s National Essay Award), has again tried to reach a broad public with Umbrales (‘Thresholds’), written during the pandemic by Óscar Martínez, who teaches at Escola d’Art i Superior de Disseny de València. A journey through western culture using its doors, which albeit not exactly of the literary quality of Vallejo’s has also been widely acclaimed, and was reviewed in Arquitectura Viva 236. Very different in nature but likewise devoted to thresholds is La beauté du seuil (‘The Beauty of Boundaries’), an exquisite text on the Japanese aesthetic of limits, first published in 1966 by the architect and professor Itō Teiji (1920-1970) under the title Kekkai no bi, and translated into French in a critical edition carried out by the architect and anthropologist Philippe Bonnin, emeritus research director at the same CNRS (Centre national de la recherche scientifique) that has given us this erudite and fascinating book.

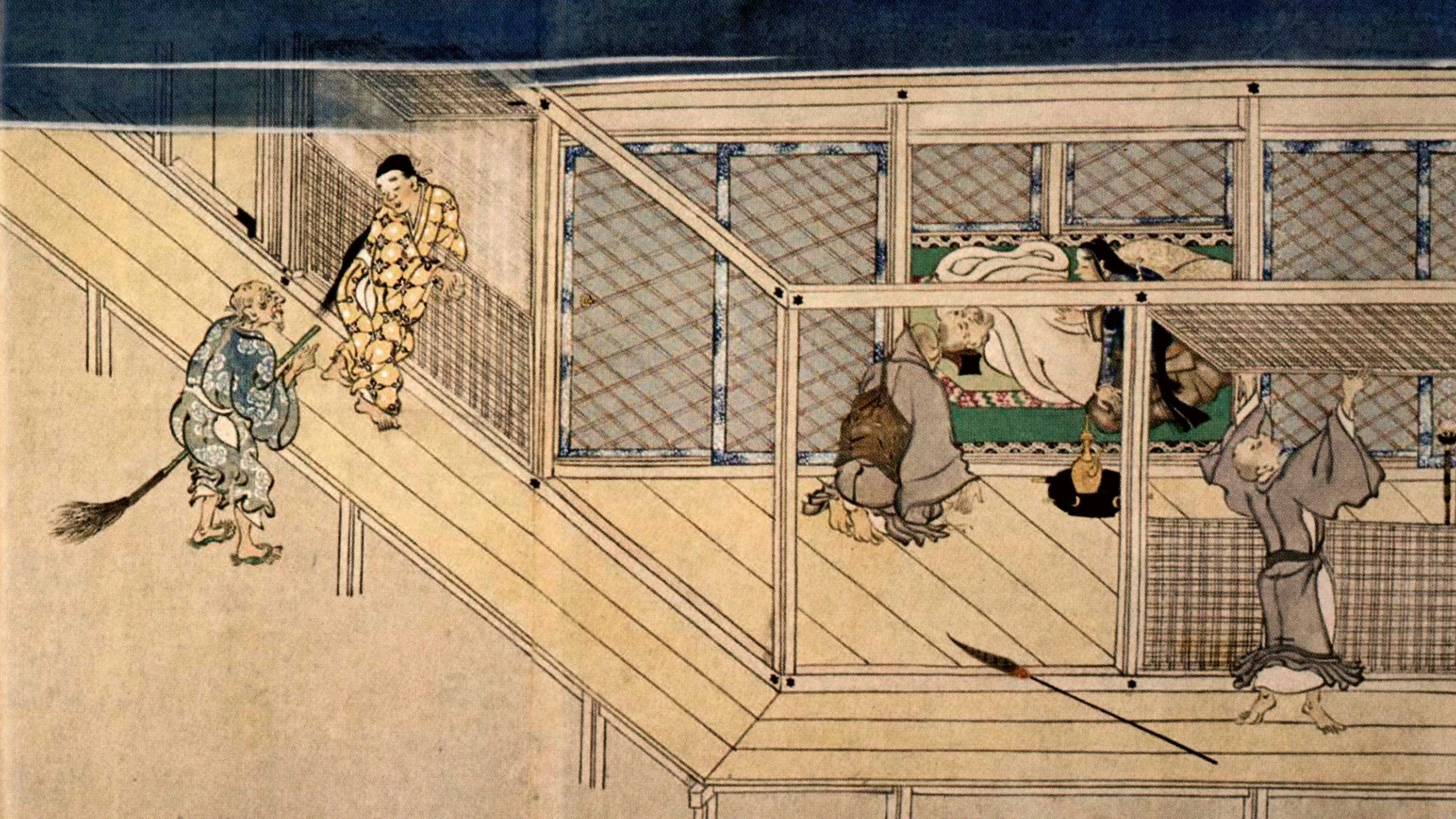

The concept of the boundary, which is also present in landscapes, poetry, and painting, is indispensable to an understanding of the traditional Japanese architecture of houses and temples, and is explored here in four chapters that successively tackle the threshold, the window, the enclosure, and the door: the threshold or kekkai marks borders with lattices, curtains, rice paper, or silk, giving an inkling of the interior through transparencies; the window, usually with laths, ranges from the generous apertures of the Zen monk’s study-library to the triangular openings of the gable end on the roof, passing through those designed ritually in the shape of a flower; the enclosure includes walls, partitions, and palisades that separate the domestic space from the landscape, “preferring charm and melancholy to security”; and the door allows the pride of ‘appearing in majesty,’ whether that of the aristocrat, that of the samurai, or that which closes the fortress. This historical and literary journey shows us the constructive materiality and the symbolic dimension of Japanese architecture, but it is above all an indispensable introduction to its aesthetic.

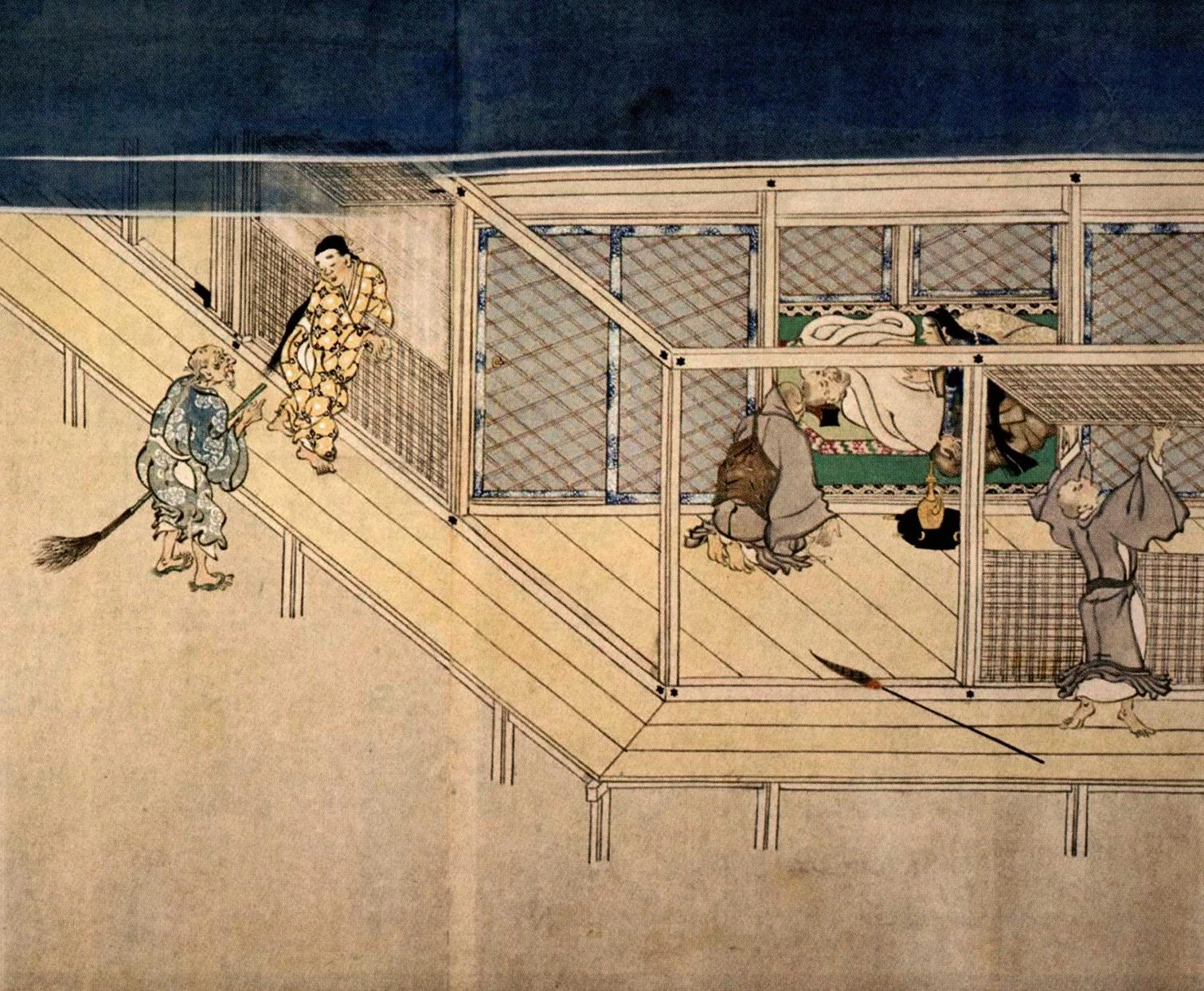

The original Japanese book is illustrated with extraordinary black-and-white images by Iwamiya Takeji (1920-1989), a photographer who was part of the 1960s movement of revival of Japanese culture, along with Tange Kenzo, Isozaki Arata, or Noguchi Isamu, all the names written here in the order that is customary in the country, so as to respect the convention followed by the book itself. In the current French edition the photos are re-takes in the same places, painstakingly located and visited to capture them in their current state, and in several cases adding color images that rigorously document the architectures losing some of the extreme abstraction of the originals, which by cropping out the curved roofs and other elements then considered parasitic, managed to make the historical works look like Mondrian canvases. Provided with numerous indexes, chronologies, and notes, in addition to an excellent bibliography, the book is a gem that fuses research with poetry and rigor with pleasure.

The dossier of color photographs of each of the book’s four parts begins with an illustration taken from the Scrolls of miracles at the Kasuga shrine, while the black-and-white images contrast the originals in the 1966 volume – which through cropping emphasize the abstract character of Japanese architecture – with recent pictures presenting the buildings more conventionally and faithfully.