Spirits and Specters

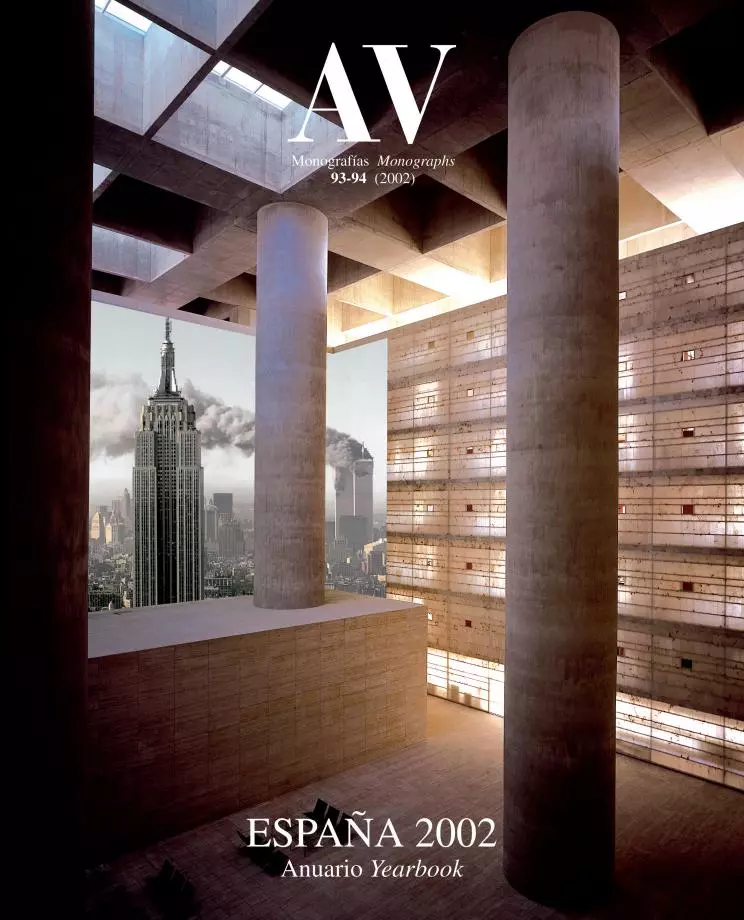

The Towers of Light on New York’s Ground Zero are proposed as a symbol of strength and hope, but could also be perceived as a ghostly presence

They wish to be spirits, but could instead be-come specters. The towers of light that artists and architects have conceived to rise skyward from the rubble of Ground Zero are well-intentioned and laudable in their aim of filling the painful void of the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers with an immaterial sign of resurrection and resistance. However, this luminous gesture on the Manhattan skyline brings to mind the columns of light that were created for the mass rallies orchestrated by the Nazi party in Nürnberg. It is therefore likely to draw ghostly, ominous connotations of totalitarian power. At a moment in which we are torn between the protagonism of terror and a desire for security, these pillars of light are not the best symbol of democratic fortitude and the solidity of civic liberties that form the tenacious spirit of societies threatened by the heinous specter of fear.

El carácter virtual de las primeras propuestas para ocupar el vacío de las Torres Gemelas contrasta con la presencia devastadora del bombardero B-2 Spirit o el cañonero AC-130 Spectre en la campaña norteamericana contra Afganistán.

The idea came from two architects, named Paul Myoda and Julian LaVerdiere, who had spent six months working on the 91st floor of the north tower, preparing a luminous sculpture that would have been put up the next year on the building’s anten-na. Moved by the tragedy of 9-11, they set about transforming their modest bioluminiscent project into plans for a colossal installation they called Phantom Towers, two shafts of light rising above Manhattan’s skyline, widely publicized since its ap-pearance on 23 September on the cover of the Sun-day supplement of The New York Times. Two ar-chitects (John Bennett and Gustavo Bonevardi) who happened to have been working on a similar idea joined in, and the final result shows two beams of white light projected by laser generators from the docks of the Hudson, rising slightly off the exact spots of the ill-fated towers so as not to interfere with the clearing work still to go on at Ground Zero. It is this proposal, rebaptized as Towers of Light, that New Yorkers are now debating on.

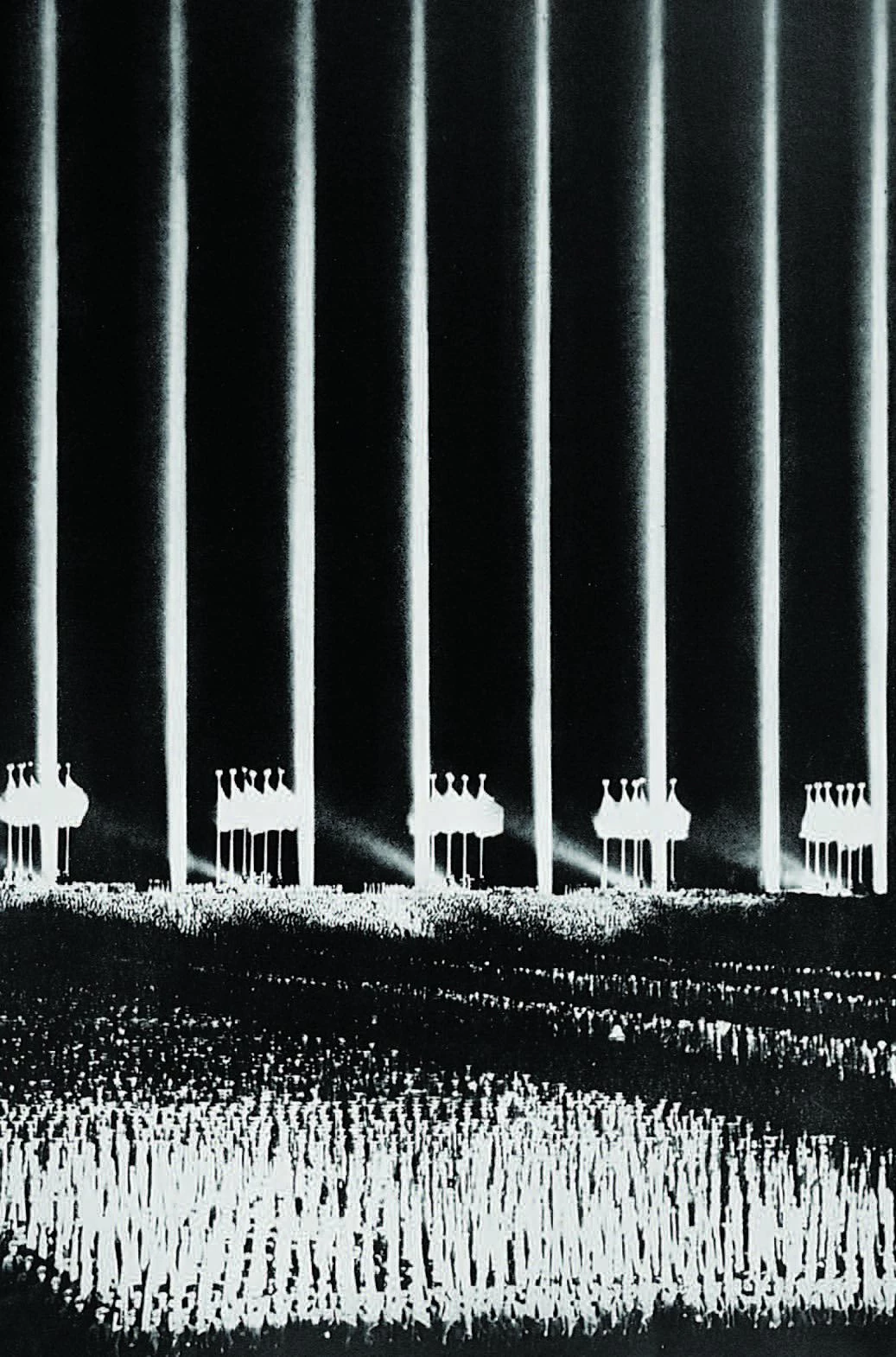

To a European, the image of reflectors conjuring solemn architectures is irrevocably associated with the Cathedral of Light erected by Albert Speer in Nuremberg’s Zeppelinfeld, a phantasmagorical and titanic nocturnal installation consisting of a pleiad of heaven-pointing parallel spotlights delimiting the scene of parades and rallies of up to a million people that were part of the paraphernalia of the congresses organized by the German Nazi party. Like hypnotic music and the choreography of masses inspired by the Wagnerian pageants of Bayreuth, these immaterial and unanimous archi-tectures were at the core of the fascist conception of politics as spectacle, and such grandiose dramawhere delirium takes the place of dialogue is now the pet vehicle of a religious or romantic messian-ism that utilizes the media with astounding skill. Bin Laden uses videoclips of Al Yazira the way Hitler did movies of Leni Riefenstahl, and the Saudi’s truc-ulent theater of terror sweeps from the screen the coverage of CNN or Fox with its tedious patriotic slogans and narcotic telegraphic crawls.

The appearance on cover of The New York Times Sunday supplement of the ‘Towers of Light’, designed by the artists Paul Myoda and Julian LaVerdiere with the architects John Bennet and Gustavo Bonevardi, made the idea very popular.

The people of Germany, who for obvious reasons are especially sensitive to social symptoms that may indicate an incubation of the totalitarian disease, already showed their indignation when someone proposed for Berlin’s turn-of-millennium festivities a luminous scenography reminiscent of Nazi cele-brations, and they have now in Nuremberg inaugurated a documentation and exhibition center that, under the title ‘Fascination and Terror’, seeks to explain the mechanisms of propaganda and media manipulation that served the National Socialist German Workers’Party. The chief designer of this communication strategy was, precisely, the author of the Cathedral of Light, the architect Albert Speer, in whose grave and rhetorical congress palace the above-mentioned center is located. Designed by the Austrian Günther Domenig on the basis of fractured geometries of steel and glass, it aims to deconstruct the perpendicular, severe solemnity of the building of the Third Reich.We Europeans were rescued from that iniquitous empire by the United States, so what a deplorable paradox of history if theAmerican peo-ple, in the wake of 11 September, were now to choose to express their strength and resolve through sym-bols stained by totalitarianism.

In any case, the controversy about the future of Ground Zero, in which hundreds of New York architects have participated, is not as important as that concerning the prospects of skyscrapers and emblematic buildings in the current climate of security paranoia. As the ashes cool, some now dare to state in public what many have already said in whispers, and thus a voice with the authority of Harry Seidler – the Australia-based Viennese architect who has designed some of the planet’s tallest buildings – has reminded us that the extraordinary fragility of the WTC had its origins in the fact that many security measures were uncomplied with for economic reasons, and this was possible only be-cause the developer and the supervisor of the complex were the same public organism. As has been suggested, this vulnerability of the towers may have been known to Osama bin Laden, who made his fortune in building, or by Mohamed Atta, who studied architecture. But these denunciations hardly alleviate the growing distrust of the highrise, no matter how much architects insist that to renounce the skyscraper is to surrender to terror.

The ghostly shafts of light over the sky of Manhattan convene other specters of a sinister past: Albert Speer’s ‘Cathedral of Light’ for Nuremberg, designed in 1934 as the stage for the Nazi Party mass parades and rallies.

Meanwhile, in the ‘McWorld against Yihad’war that is having its first episode in Afghanistan, the West hammers against a swarm of wasps without yet understanding the nature of the new conflicts and the new enemies, whom we could try to defeat without demonizing them or characterizing them as cartoon villains, perverse Lex Luthors or sinister Darth Vaders in possession of the dark side of force. The destruction of New York’s Twin Towers was an act of violence so extreme and exact that we insensitively liken it to a simulation in virtual reality, or even to a demolition of a symbolic purity as horrifying as that of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, forgetting the killing of thousands of people which we would be shocked to consider a collateral damage of the spectacle of politics.

We also thus perhaps imagined the Afghan war as a confrontation that would be fought in the immaterial field of screens, one where the protagonists would be intelligent bombs launched by uncrewed aircraft like the Predator, or by the invisible fighters and bombers of the Gulf and Balkan wars, the origami-like F-117 Nighthawk and the undulating B-2 Spirit. But entrance into Kabul has been possible only thanks to the cruel fragmentation bombs and the devastating Daisy Cutter, the crude carpet-bombing of the B-52s which have reached there 50 years in service, and the overwhelming fire of the AC-130 Spectre, the artillery version of the veteran Hercules. We expected a subtle war of spirits, and have had instead a terrible war of specters.And now the phantoms threaten to rise over the heart of Manhattan, evoking ominous presences.We have always feared and fought the others; it would be tragic to discover that the others are ourselves.