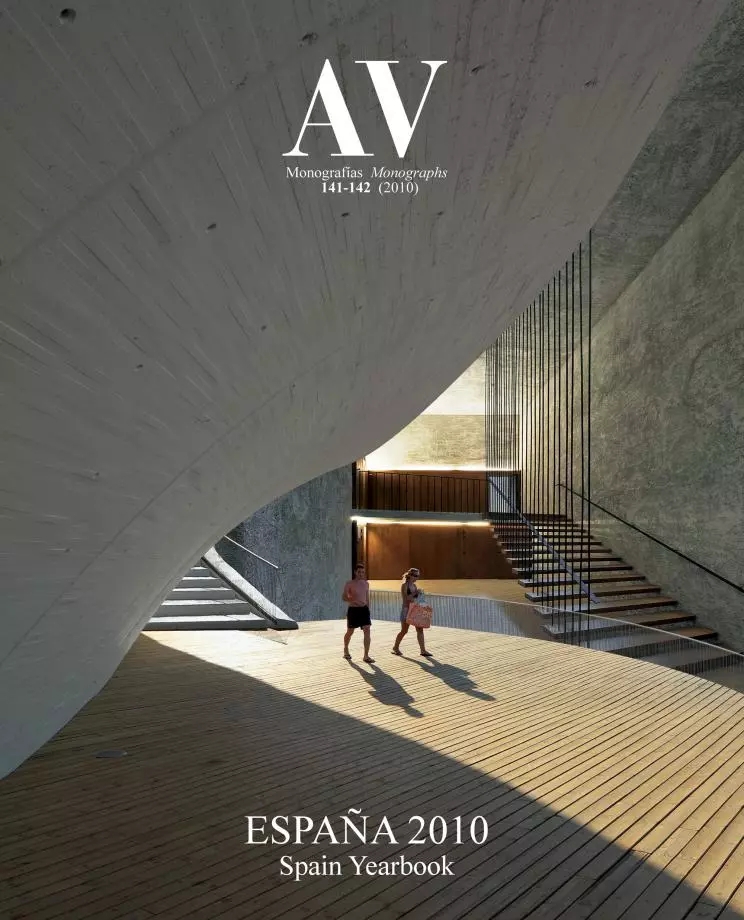

Criticism and Crisis

The different crises of the planet – related to climate change, the economy, terror or catastrophes–, prompt to redefine the bases of architectural criticism.

The crisis of criticism has been washed out by the crisis of the world. In the first essay of Paul de Man’s Blindness and Insight – whose title has been borrowed for this text – the literary theorist argues that “all true criticism occurs in the mode of crisis”. Quoting the 1894 Mallarmé lecture at Oxford (“They have tam- pered with the rules of verse... On a touché au vers”), de Man applies the words of the French poet to the literary criticism of 1970: “On a touché à la critique... Well-established rules and conventions that governed the discipline of criticism and made it a cornerstone of the intellectual establishment have been so badly tampered with that the entire edifice threatens to collapse”. But this mode of crisis, which does not necessarily affect historical or philological approaches, is indeed inseparable from criticism: “to speak of a crisis of criticism is then, to some degree, redundant”.

When de Man was writing, his commentary could be easily applied to the discipline of architecture. After the 1966 books by Venturi and Rossi, the intellectual situation of this field could be described with the same words: “On a touché à la architecture... Well-established rules and conventions have been so badly tampered with that the entire edifice threatens to collapse”. The rules and conventions were of course those of modernism, adopted after World War II as the canonical mode of building, and this first postmodern refusal would be followed by the unstable, fractured forms of deconstructivist architecture and by the warped, shapeless constructions of computer-designed bubbles and blobs. Now, four decades after the crisis of modernity which shattered architecture and criticism, the material crisis of the world – from global warming or financial melt-down to human catastrophes or widespread terror – brings forth the awareness that the edifice in threat of collapse is the planet itself.

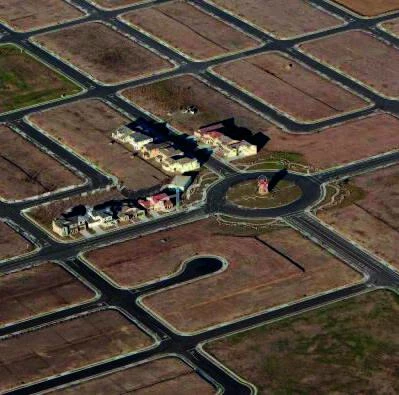

The site of a residential development awaiting to be occupied in the US or the roads covered by desert sand in Dubai illustrate the real estate crash that made banks stumble and has devastated real economies worldwide.

Before the grim reality of the collapse of global governance, the task of architecture becomes the very dumb one of providing some order in the midst of disorder, and the task of criticism ends up being the even duller of offering support and encouragement for the constructions that hope to heal rather than to those that attempt to replicate the chaos of the world. So expressed, the purpose of criticism seems intellectually shallow, or downright trivial, but perhaps our historical time demands the humility of simplicity, not only in our lives, but in our very thoughts. Being stupid is a way of being wise in times of distress, and shedding the elaborate cloak of intellectual pretence is akin to denuding architecture of superficial ornament, going to the root of things and claiming for architects a role of service which has been forgotten in the unholy liaison with celebrity and glamor.

Architects have been very successful delivering built icons for cities and countries, but much less so addressing the current predicaments of a world torn by pain and anxiety. Their most influential intellectual figures have embraced a caricature of commerce as their almost single ideological reference, and the utopian aspirations of modernity have all but vanished in a climate of extreme cynicism. The discipline of architecture, for so long the province of monarchs or tycoons, blurred its connection with power in the first decades of the 20th century, and clinched a deal with the social realm that placed the everyday lives of ordinary people at the center of its attention, but this pact has since been erased by the emergence of spectacle as the dominant trait of contemporary societies.

The current awareness of the fragility of our political and economic structures – which renders the cult of spectacle both obscene and obsolete – demands a renewal, a hundred years later, of the social contract of modern architecture: a renewal that cannot be innocent and guiltless, but a renewal that cannot either indulge in skepticism. It is indeed a steep road, one that demands constant attention, and one that may in the end lead nowhere. But it is the only road that offers a glimpse of hope, and the only one that it seems decent to follow. This is our meek and stupid way forward: creating islands of order in a sea of disorder, and offering shelter from the pain of chaos. Italo Calvino described movingly this path in the closing sentences of his 1972 Invisible Cities: “seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space”.

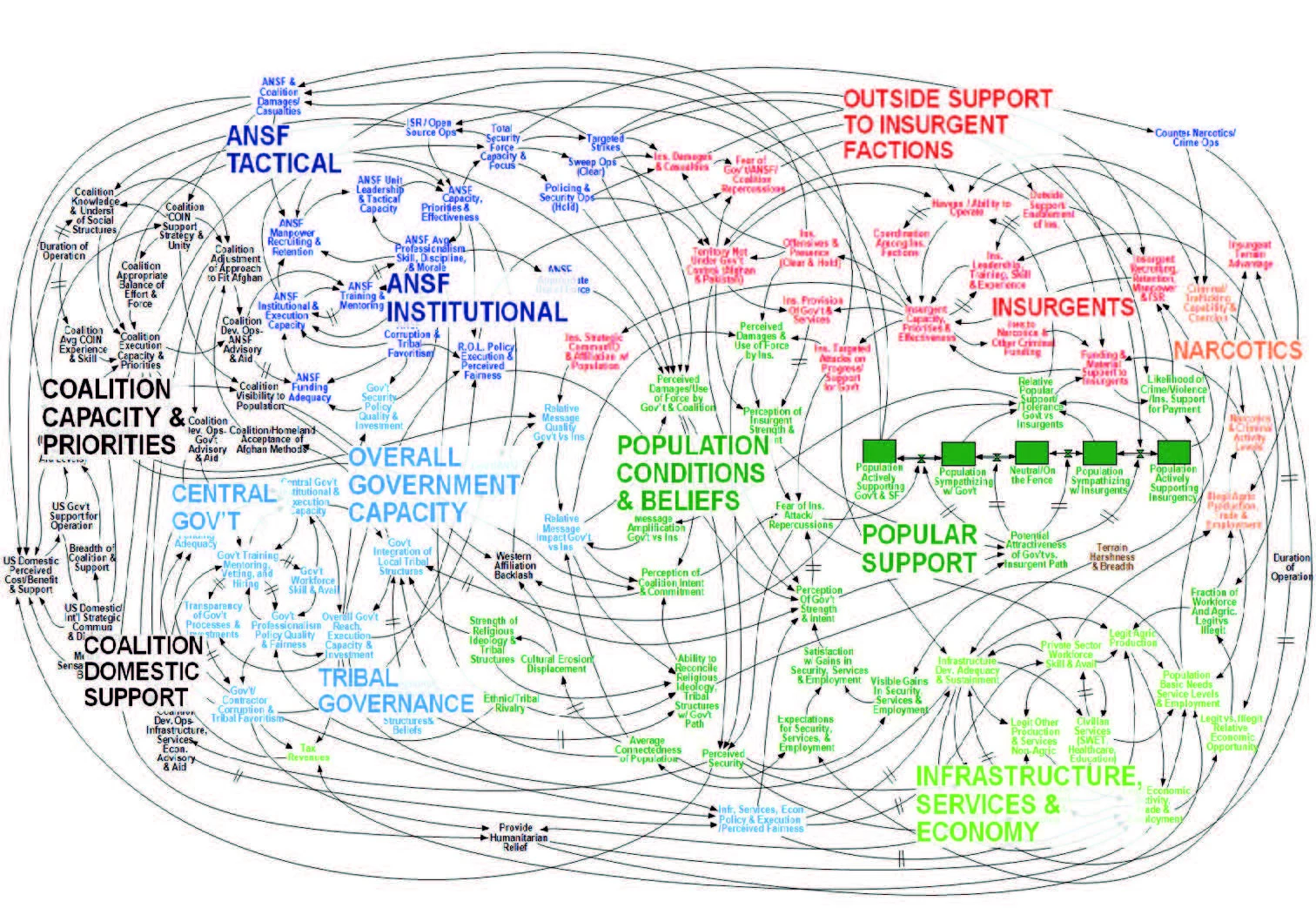

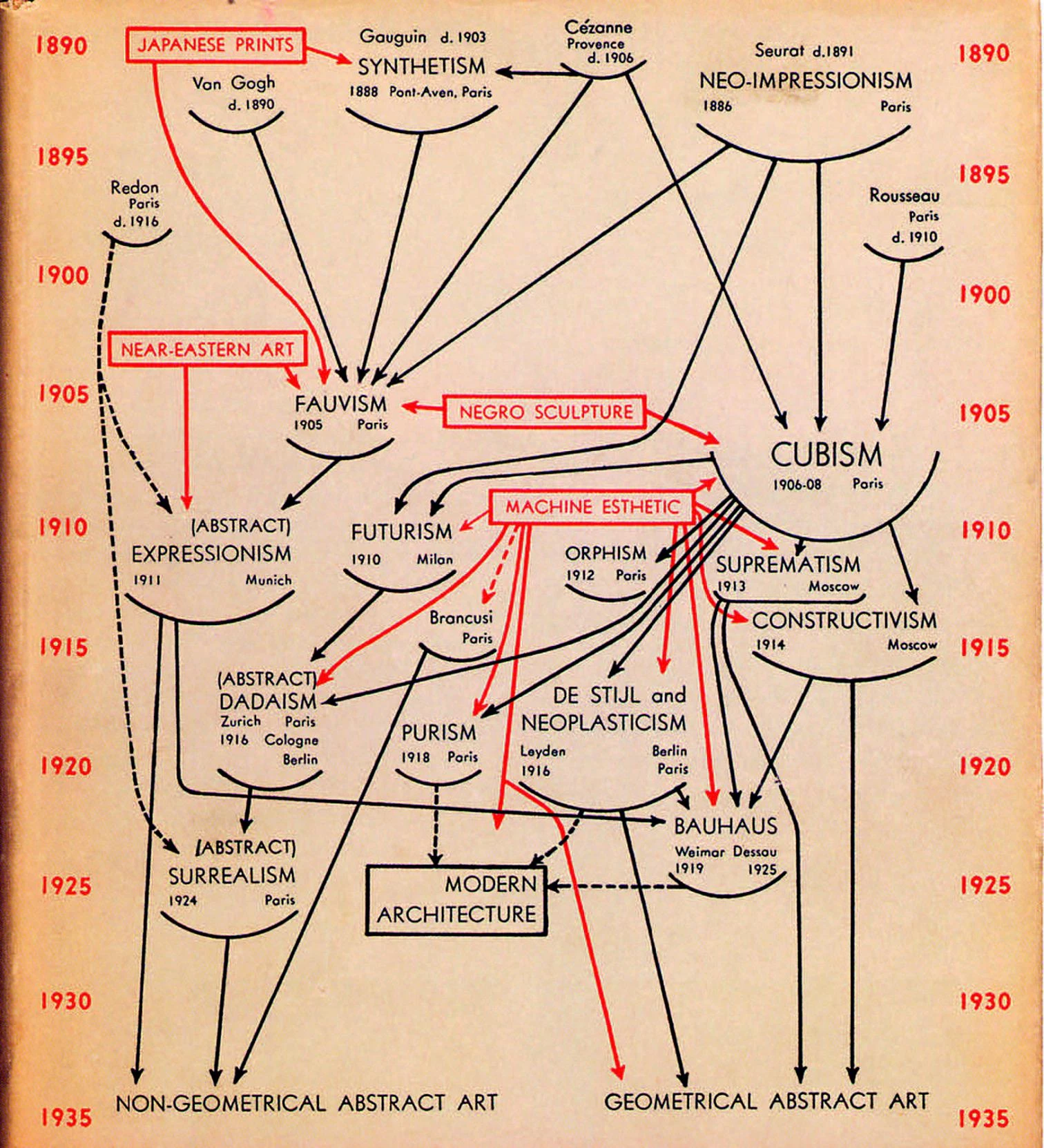

Between the intricate chart summing up in 2009 the US strategy in Afghanistan and the elegant diagram used byAlfred Barr in 1936 to explain the development of abstract art there is less than a century, but a true conceptual abyss.

If this sounds like a halfhearted attempt to give breathing space to a sadly jaded humanism, it is probably because, as Mark Lilla has suggested, too many of us followed “a false messiah into the desert of deconstruction”, and the intellectual backlash has an element of despair that grabs on to the more unexpected holds. In Les voix du silence of 1951, André Malraux wrote that “nous voulons retrouver l’homme partout où nous avons trouvé ce qui l’écrase”, and this will to rediscover humanity in hardship has an ethical value that cannot be allowed to fade. The crisis of the world demands that criticism give voice to silence, and make visible both invisible cities and invisible architectures.