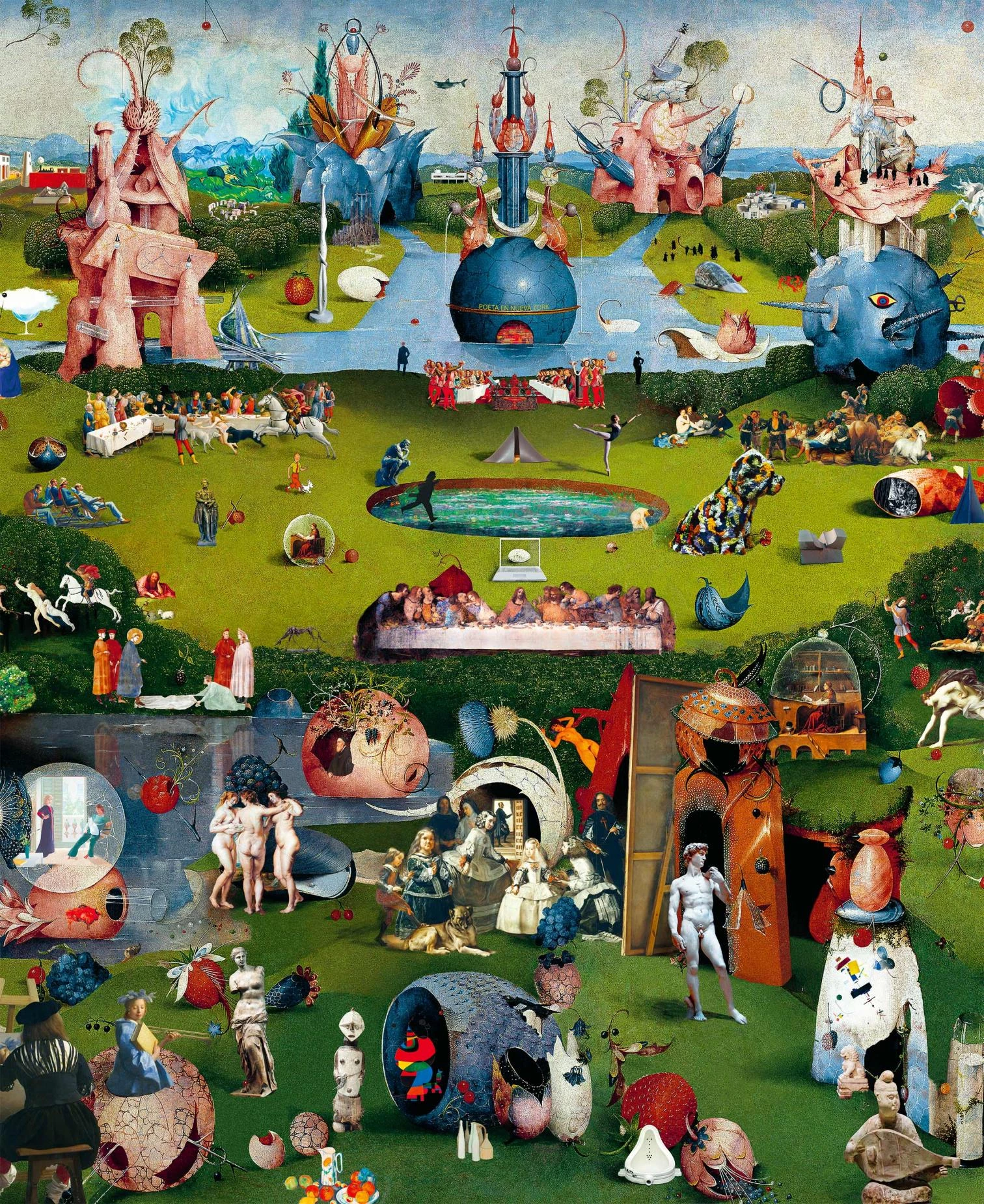

José Manuel Ballester, Garden of art, 2021 (fragment)

The dream of Utopia gets enmeshed with the shadow of the Apocalypse. Arriving at this point of our journey, reaching issue 250, we wish to throw the light of useful utopias on a landscape dimmed by economic decline, epidemic threats, and the devastation of war, all this in the context of a climate emergency. But the oneiric component of utopias can engender monsters, and here we have added the adjective ‘useful’ in order to push them toward the domain of the everyday and thus try to keep reason awake, and dreams reasonable. In the course of history, many projects for ideal communities resulted in totalitarian nightmares, and in fact many dystopian fictions are born out of disappointment or frustration with social utopias, be it Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World or George Orwell’s 1984, dystopias of 1932 and 1949, respectively, that denounce industrial capitalism, communism, and fascism, or the Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, a novel published in 1924 that inspired both of the above with its portrayal of a future society completely subjected to the State.

In our time, books and films compete in presenting post-apocalyptic narratives, and techno-totalitarian dystopias like Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou’s Metropolis, Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville, or Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 have given way to the violent chaos that ensued from the catastrophe, where the authority of The Benefactor in We or of Big Brother in 1984 no longer exists. The dangerous and desolate ash-filled world depicted in The Road, the novel by Cormac McCarthy that hit the big screen in 2009, marks the freezing temperature of these depictions of a devastated Earth; and the impotent paralysis of the characters in Melancholia, the 2011 picture where Lars von Trier tells of the anguished wait for a rogue planet to collide with Earth, provides a metaphor of our incapacity to fight climate change and prevent environmental disaster. Post-apocalyptic or pre-apocalyptic, these stories have made it easier to imagine the end of the world, and doomers are colonizing literature, cinema, theater, the arts, and even video games.

Amid so much gloom, in Arquitectura Viva 237 we reviewed books of hope in ‘Against the Apocalypse’ – a text which also closed The Age of Discontent – and now we explore those ‘useful utopias’ with an article about the ideal city that does not forget Babylon’s warning; a presentation of artistic brotherhoods that underlines its contemporary pertinence; an essay that endeavors to root domestic alternatives in the common sphere; and a prologue that presents the thesis of a long 20th century during which humanity pursued its utopia in freedom and prosperity. This zoom of history is complemented by eight pieces by masters being asked which architecture should be upheld in the current context of crisis, plus a lecture that uses the late style of writers and artists to suggest the challenges involving heritage, landscape, and the planet. Finally, using the Hippocratic oath as model, this issue closes with a possible Vitruvian code, summarizing architecture’s ethical obligations in the face of both the dream of Utopia and the shadow of the Apocalypse.

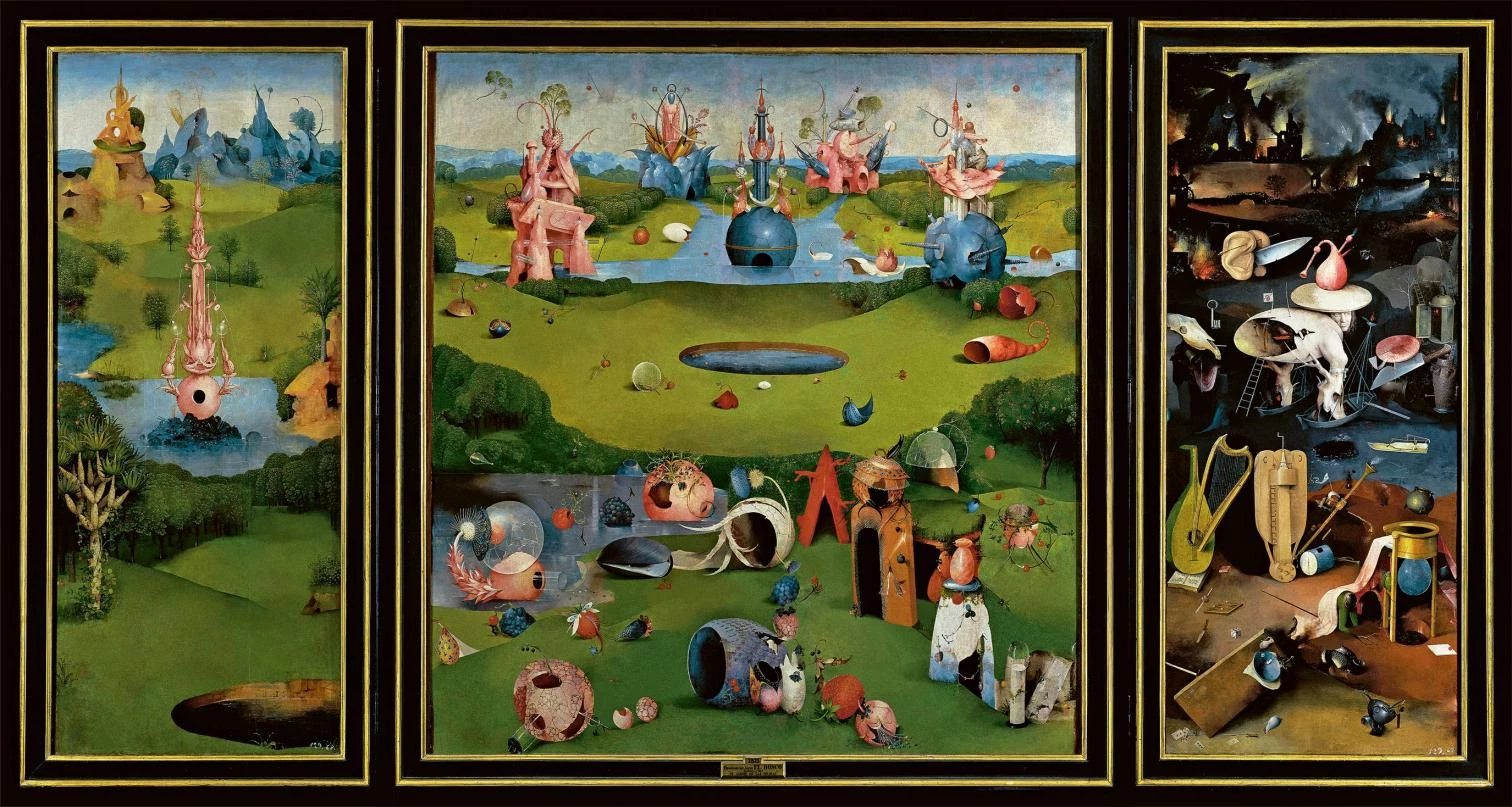

José Manuel Ballester, The uninhabited garden, 2008