A few months before he died on January 13, Aldo van Eyck celebrated his eightieth birthday with the publication in English of the biography written by Francis Strauven. For many of us, the Dutch master could be summed up through a handful of telegraphic references: CIAM, Team X, Forum, Dogon, Orphanage, Sonsbeek, Hubertus, ESTEC. This apocopated resumé takes stock of his participation in the final editions of the CIAM, which he helped dissolve; of his membership in Team X, which he had founded with the Smithsons, Candilis and his compatriot Bakema; of his editorship in the journal Forum, which became the voice of the rebellious spirit of the sixties; of his passion for vernacular African architecture, particularly for that of Mali’s Dogon tribe; of his masterful orphanage in Amsterdam, which was to be the most characteristic work of Dutch structuralism; of the torn down Sonsbeek sculpture pavilion, emblem of the ‘labyrinthine clarity’ of his humanist structuralism; of the Hubertus home for mothers and children with problems, so disconcerting in the unclear labyrinth of its geometries; and of the headquarters for the European space agency, whose multicolor hendecagonal order would be his final provocation. Strauven’s book enriches these biographical milestones with a constellation of personalities that gives us a better understanding of Van Eyck’s ideas and oeuvre, ranging from the extraordinary duo formed by his parents (a poet-philosopher divided between diplomacy and literature, and a passionate woman born in Surinam for whom the old Dutch Guiana remained a lost eden) to his sensitive and devoted wife, Hannie, who be-came his professional colleague at an age when others retire, and from the charismatic Carola Giedion-Welcker in a Zürich removed from the war, to the artists of the CoBrA group in experimental postwar Amsterdam.

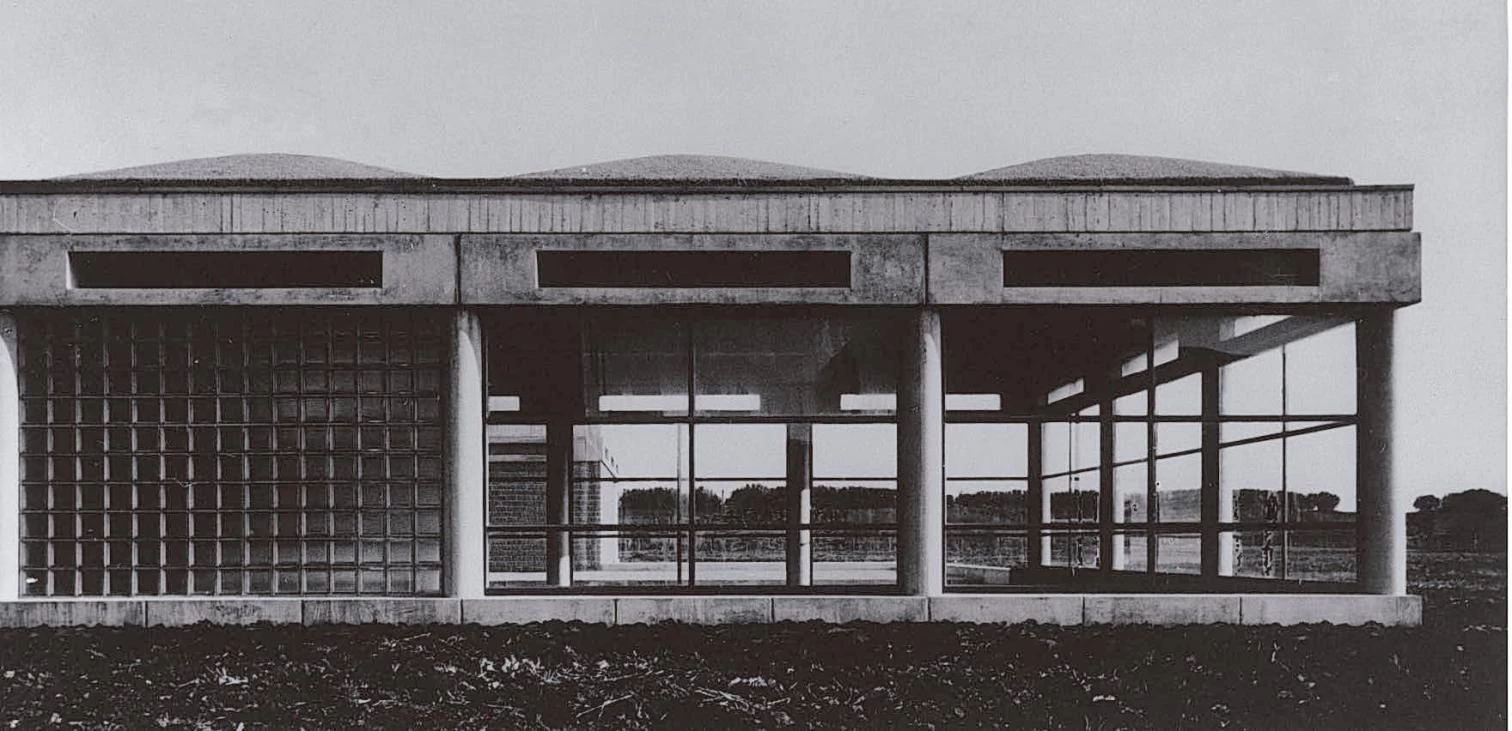

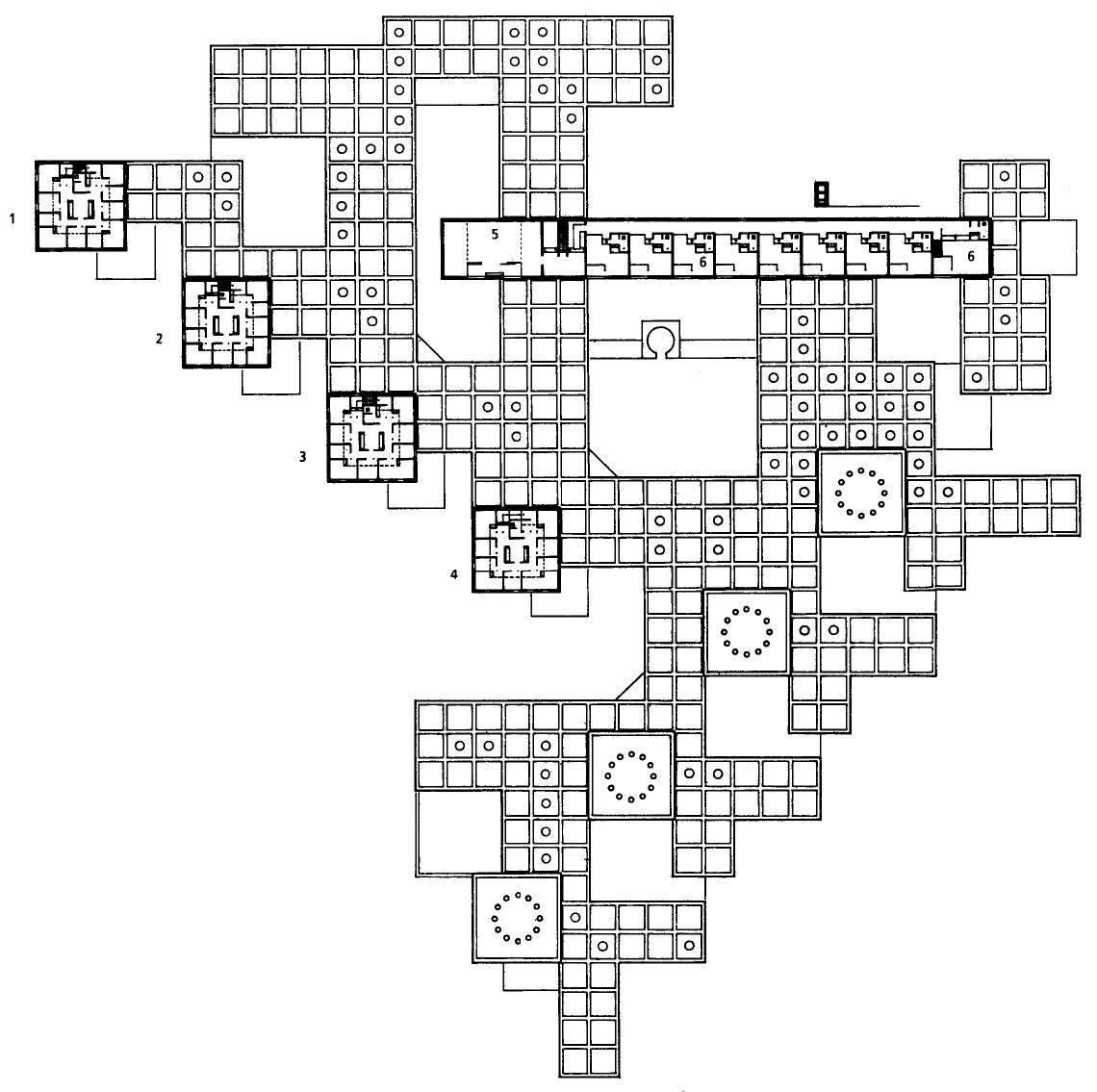

Following his revision of modern architecture, undertaken from a humanist point of view, Aldo Van Eyck designed the Amsterdam orphanage, which became the key work of Dutch structuralism.

When the biography was first published in Dutch in 1994, Van Eyck and Strauven presented it in the orphanage, which then housed the Berlage Institute of Architecture, with Herman Hertzberger as director. The venue selected for the event was especially appropriate, for here was a masterwork of Van Eyck which, having ceased to serve its original purpose, had been spared demolition through the ex profeso creation of an institution for architectural education and research, named in honor of the greatest of Dutch architects. The building’s at once domestic and public scale had proven so apt for a children’s home, and now perfectly accommodated the combination of seminar facilities, workshops, classrooms and assembly halls that an academic center requires (a paradoxical and melancholic proof of such flexibility is that, unable to pay the high rent and forced to move elsewhere, the Berlage Institute – created to save the building! – has given way to corporate offices whose layout adapts just as comfortably to its random alveolar structure). Likewise fitting was the Institute’s being headed by Hertzberger, surely the architect who had best expressed Van Eyck’s anthropological and artistic convictions, not only in the friendly field of housing and schools but also in the thornier realm of the work space, having erected precisely the Central Beheer headquarters, an office building that came to emblematize the reconciliation of necessity and freedom that the structuralism of the Netherlands so adamantly preached (the current director of the Institute is the architect Wiel Arets, and this is again another sign of the times).

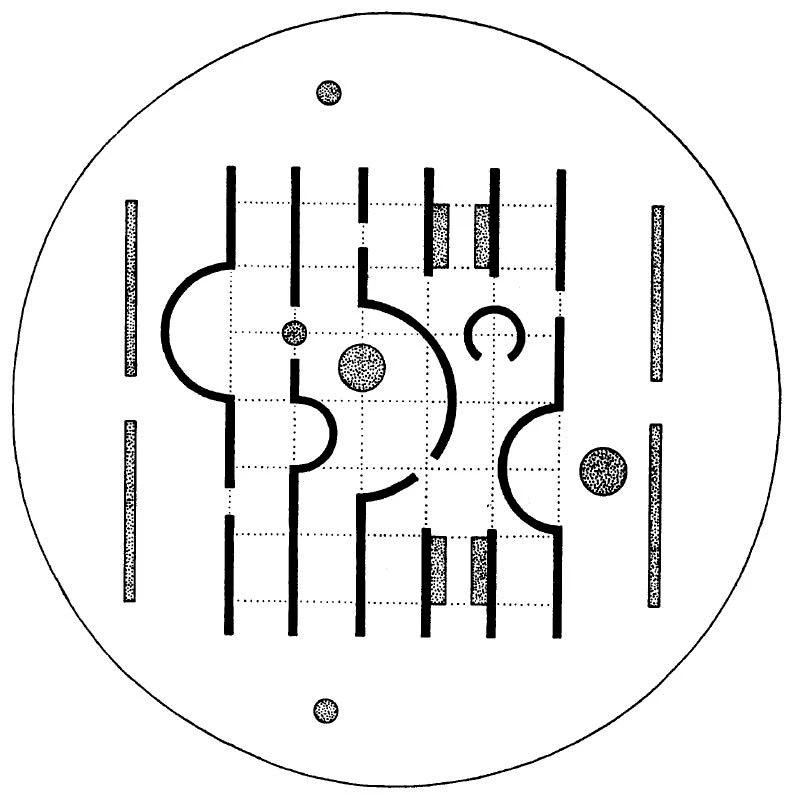

An emblem of ‘labyrinthine clarity,’ the sculpture pavilion in Arnhem bathes with even light its galleries, open to the Sonsbeek park, favoring the casual encounter between works of art and passersby.

Though the book was written in Dutch, the ceremony was conducted entirely in English, official language of the Berlage Institute, whose international vocation – evident in the recruiting of teachers and students from all over – imposes the use of this lingua franca, in refreshing contrast to the shortsighted chauvinism of other European schools. Van Eyck spoke the admirable English inevitable in one who lived his childhood and early youth in Great Britain, adorned his speech with several bullfighter’s passes, and wrapped up the faena by drawing the back curtain for the audience to contemplate, through the large windows, the neighboring office building, colossal and abominable, which the architect boasted having known how to ‘tame’. With this theatrical coup in the presentation of his biography, the charismatic master inexorably welded the more acknowledged part of his life’s work to its least appreciated: the egalitarian, optimistic isotropy of the sixties and the capricious, coloristic geometries of the nineties; the orderly tapestries and the unexpected grids; the articulated, tectonic concrete and the glazed panels with rainbow frames. There is some continuity, to be sure, between the communal, countercultural Utopias of the sixties – when all the world’s schools of architecture paid more heed to Eskimo igloos than to Palladio villas – and the ‘socially responsible’ mask that aspires to give a human countenance to the large bureaucratic corporations; but in the old Dutch master one did not know whether to look for it in the desire to join the homo faber to the homo ludens, or in a Peter Pan syndrome that had him reproducing an eternal childcare center with sandboxes and colorful toys.

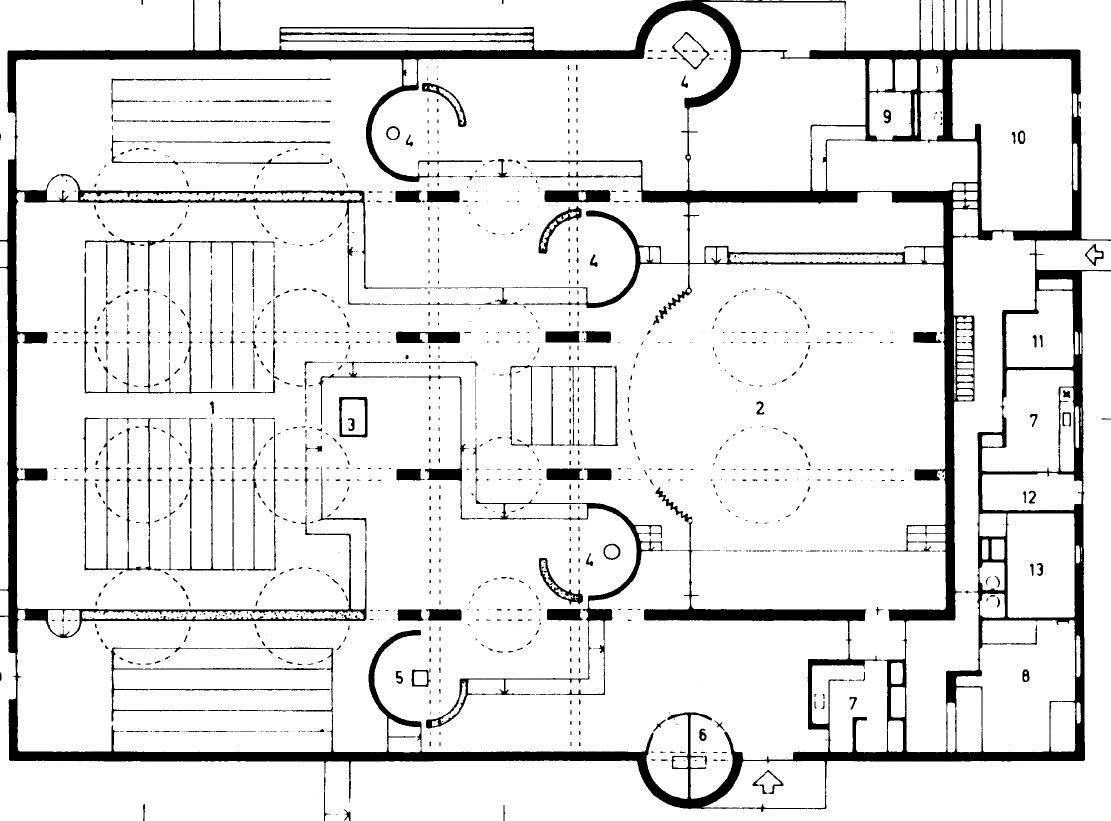

The Pastoor van Arskerk Church in The Hague undermines with its proliferation of chapels and cylindrical skylights the hierarchical direction of the traditional liturgical space, bringing the altar closer to the faithful.

Readers of this abundantly documented, confusing biography will not enjoy Strauven’s limited narrative skill, but it nevertheless offers a wealth of suggestive information and a stimulating quarry of images. Some will take an interest in what is most original about the book, which is its exploration of the roots of the anthropological thought of a Dutchman who wandered both physically and emotionally from his native country – so long contemplated from the British or Swiss prism, and so often perceived in terms of the tropical nostalgia of his mother and grandparents, or of the African fascination of his travels. Many will find particularly important van Eyck’s relations with two artistic circles of fertile creative experimentalism, that which revolved around Carola and Sigfried Giedion in Zürich, and that of the CoBrA group in Amsterdam, whose most influential exhibition he himself set up (incidentally it was also he who introduced the painter Constant into the building world, and the very earliest sources of the latter’s situationist New Babylon were the ideas of Team X and van Eyck’s children’s playgrounds). Others, finally, will reencounter in this biography of the late Dutch master the muscular dynamism of the architectural debate that characterized the Netherlands in the course of this century, the extraordinary innovative vigor and no less admirable adaptability of its built culture, and the apparently inexhaustible capacity of neoplasticism to fertilize the apparently remotest intellectual adventures of its premises. Aldo van Eyck is dead, but his work remains as alive as the orthodox modernity it sought to eliminate.