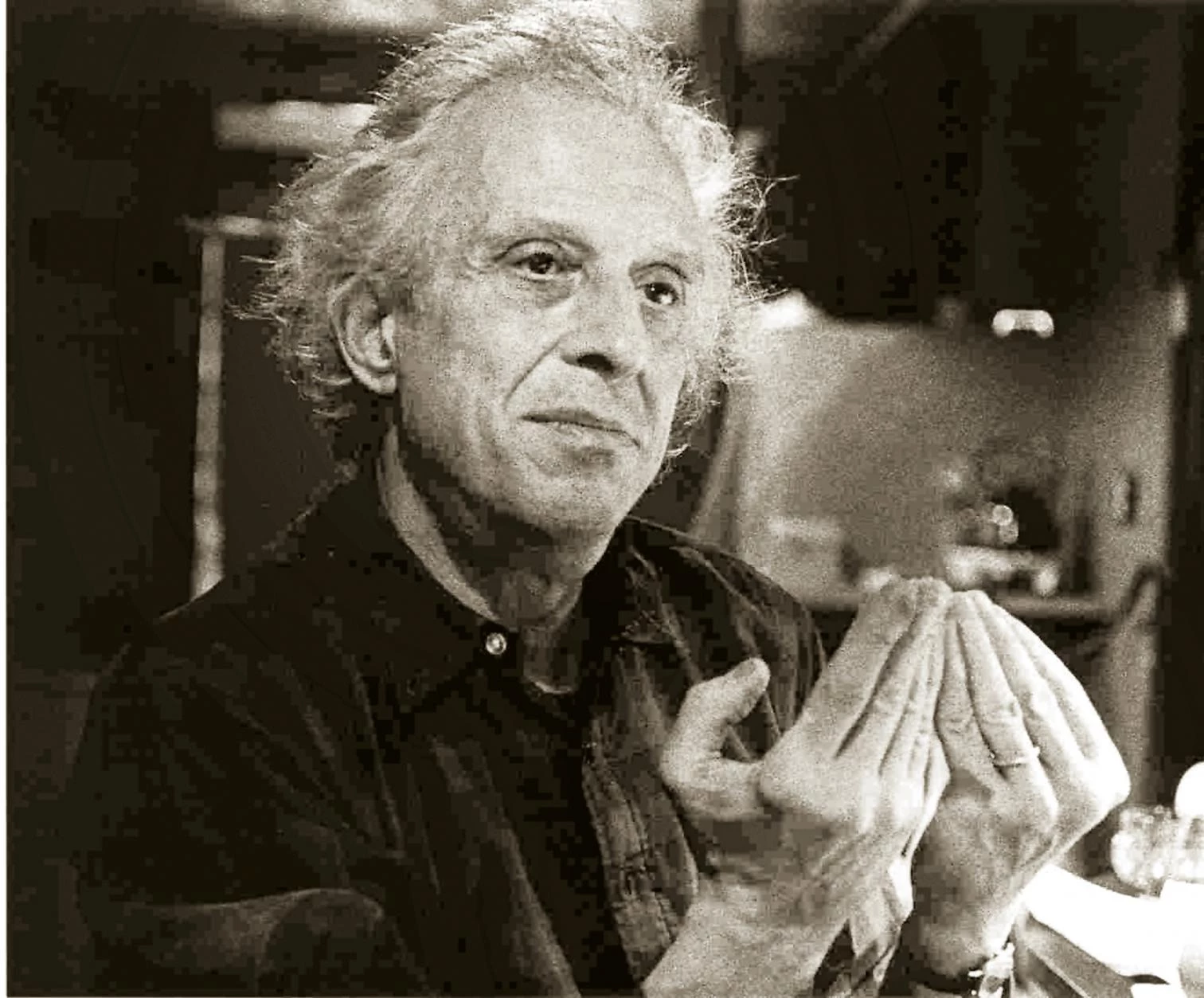

The Rebel Humanist

Aldo van Eyck (1918 - 1999)

Son of a Dutch father and a Dutch-Jewish mother, Van Eyck spent his early years in England, and during World War II he studied in Switzerland, at the ETH of Zurich, away from the Nazi-occupied Netherlands. He received his diploma in 1945, the year the war ended and the year of the beginning of the vast campaign of building for the ‘great number’ of people left homeless by both the war and the political neglect that was a feature of the 1930s.

The drive to reconstruct and construct was massive. However, by the mid-1950s, enthusiasm had much waned and there were signs of discontent, given that progress was now measured by counting ‘objective facts’ like number, volume, and size of new buildings.

Fresh out of university, Van Eyck joined the growing protest in search of less oppressive environments. His opinions emerged out of the exceedingly stimulating environment of Zurich at that time, a city that had been neutral during the war, and thus had becme a multilayered hub of exiled or self-exiled intellectuals, scientists, avant-garde artists, and of course spies.

Having himself changed country several times, Van Eyck thrived in this rich complex cosmopolitan setting, where he encountered people of very diverse origins and identities. Thus, in developing his own individual way of thinking, he sought to ‘reconcile’ diverse points of view in solutions that avoided any kind of reductive dogma. A major driving force in this search were the writings of Martin Buber, an Austrian-born Jewish philosopher he had discovered during his student years in Zurich. Buber was preoccupied with the increasing ‘dehumanizing’ effect of objects, the so-called ‘It,’ which he considered capable of destroying human relations, associated with the expression ‘I-Thou.’ Such dehumanization caused the loss of the ‘between’ (das Zwischen), ‘where I and you meet,’ making possible ‘interhuman’ dialogue (das Zwischenmenschliche) and the reconciliation of differences.

Dialogue and reconciliation became Aldo van Eyck’s overriding objective in all aspects of his intellectual life. As a student at the ETH, he chose to follow the classicist professor Alphonse Laverrière. At the same time, he joined the circle of Carola Giedion-Welcker, the wife of the historian Sigfried Giedion, who introduced him into the world of modern art and modern artists; in fact, in the period between 1944 and 1947, with his own savings, he purchased Picasso’s Glass of Absinthe and Dream and Lie of Franco, along with an Arp, a Tanguy, and a Mondrian. He applied the same approach of dialogue and reconciliation in his professional career when he returned to the Netherlands in 1946, employed at first by the Office for Public Works in Amsterdam, under the direction of one of the most prominent proponents of modern architecture and a CIAM leader before the war, Cornelis van Eesteren.

‘Homo ludens’

From his Amsterdam post, Van Eesteren had undertaken the colossal task of reconstructing the country. True to the vision he had espoused before the war, he applied a top-down ‘total’ planned approach to house ‘the greater number’ most efficiently. Yet he encouraged Van Eyck to follow through his critical ideas about giving more flexible, ground-up, spontaneous, immediate answers to the pressing needs of the moment. One of these answers had to do with children, whom he saw as neglected, when not suppressed and oppressed. Furthermore, he understood ‘childhood’ as having a special approach to society and life in general, in the sense that children, as champions of curiosity, chaos, and dreams, and of resistance to fake rules, were a source of endless creativity.

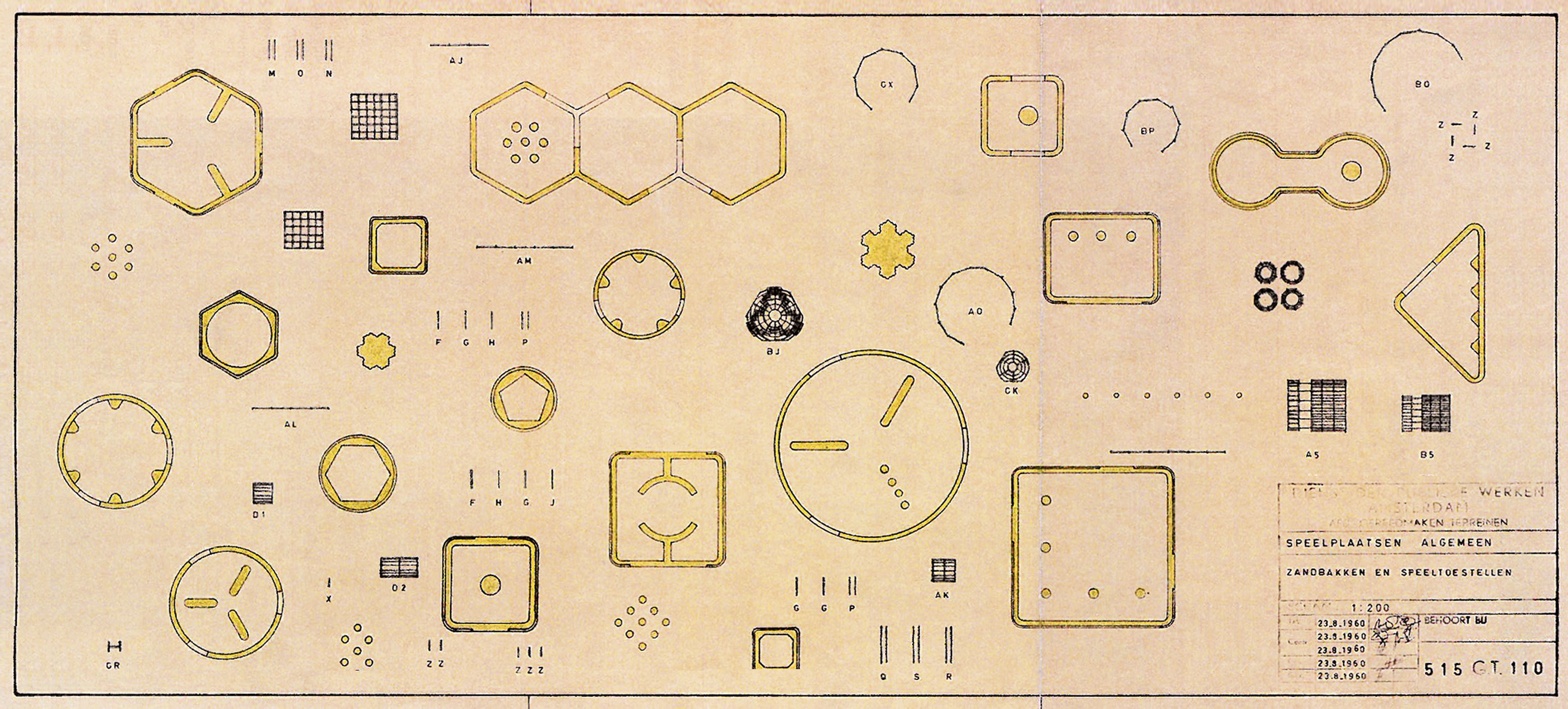

Van Eyck’s answer was the ‘playgrounds’ or ‘left-over places’ series located in voids generated by postwar urban planning; voids which, in words written by John Volker in 1954, were “formless islands left over by the road engineer and the demolition contractor,” but which Van Eyck saw as opportunities. Like the neorealist writers, filmmakers, and photographers of the ‘reconstruction’ period, Van Eyck, rather than pursuing the ‘illusion of immanence’ and abstract formulas, to quote

Sartre, chose to reflect the reality of each given ‘situation,’ alienated but also engaged with the world. Van Eyck saw these playground projects not only as remedial works but also as true avant-garde agents, as part of a ‘ludic’ manifesto for changing how we live in the city, in the same way that “after a heavy snowstorm,” our perception of the city changes altogether, taken over as it is by children, who, interacting with each other spontaneously, become the true lords of urban space.

Children and adults alike loved Van Eyck’s playgrounds or Speelplatsen. No fewer than 700 were built in the city of Amsterdam by the year 1951, most of them in response to neighborhood demands.

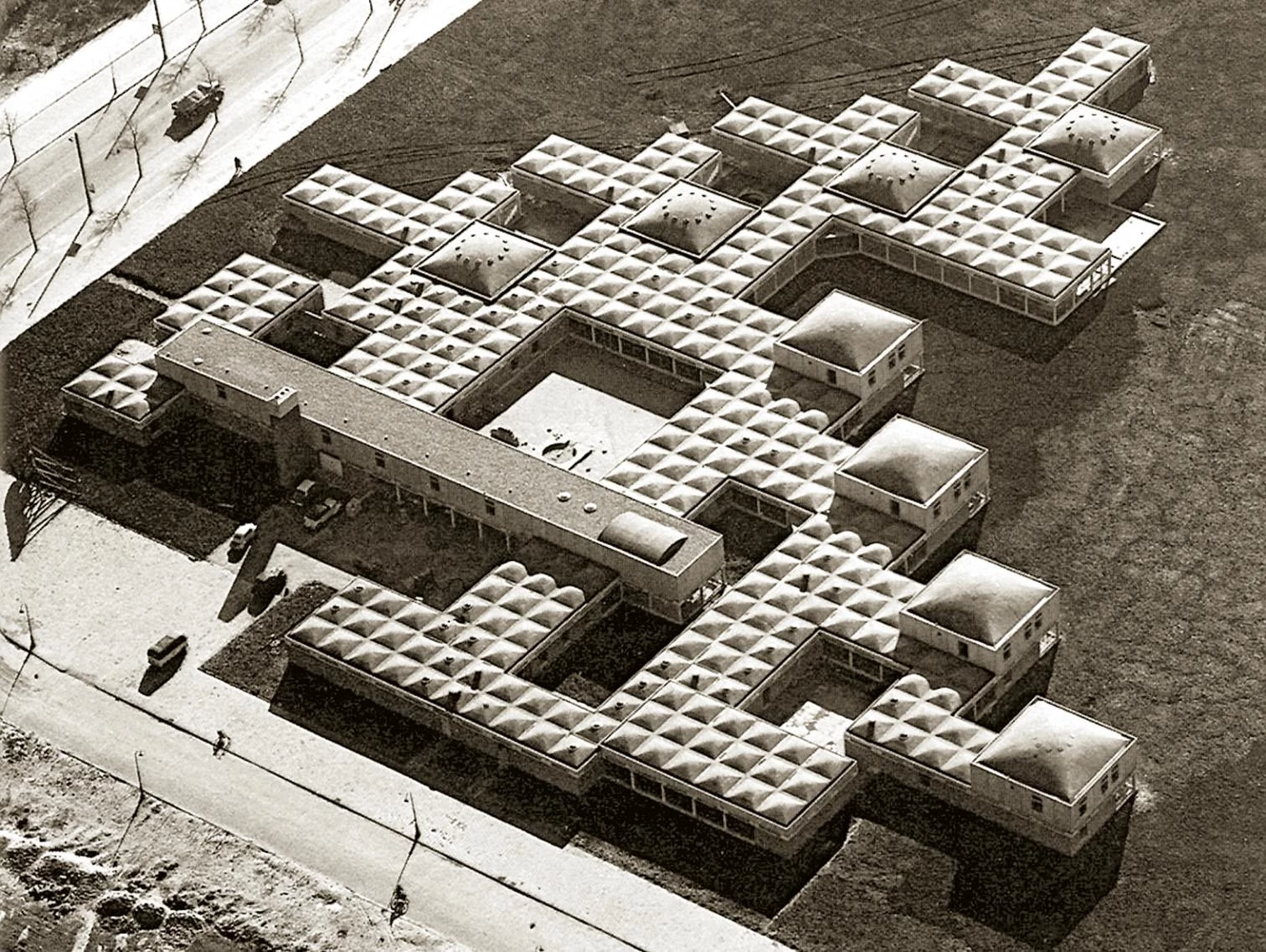

Notwithstanding, beyond the city of Amsterdam, the impact of playgrounds was limited. The project that made Van Eyck world-famous was the Children’s Home, an institution for orphans and children from broken families, outside Amsterdam.

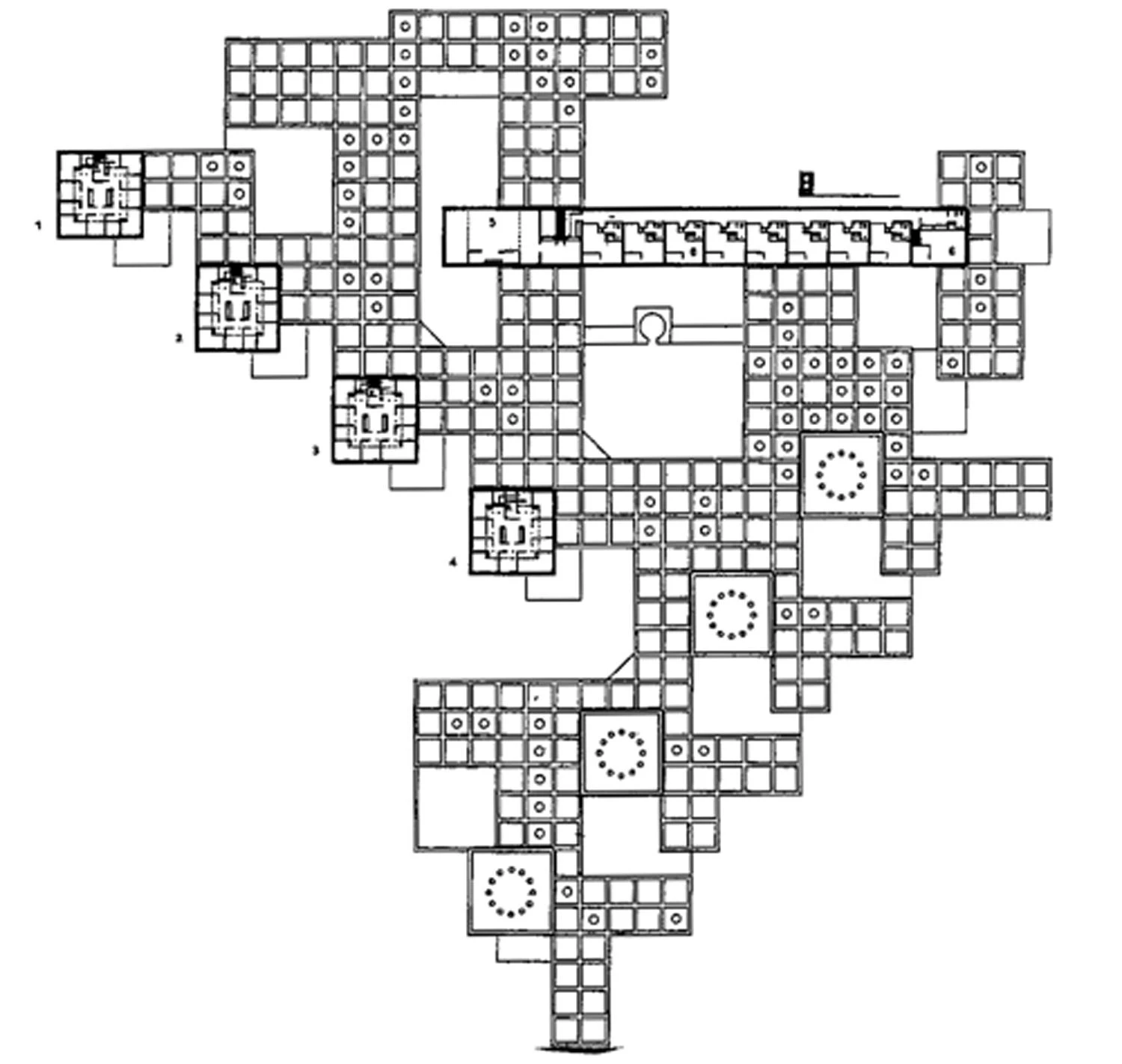

In many respects, the Children’s Home was the opposite of the playgrounds. While the Amsterdam playgrounds were small roofless minimal structures occupying crowded interstitial urban voids, the Children’s Home was a large multifunctional complex under one roof located in a vast open area, beyond the city’s periphery, its closest neighbors a stadium, the open highway, and the national airport.

As with the playgrounds, Van Eyck tried to compose the plan of the Children’s Home as a dialogue reconciling the classical canon of spatial composition with the anticlassical De Stijl system, “joined in a perfect amalgam.” Avoiding the oppressive effect of large-scale institutional buildings, he conceived a scheme consisting of repetitive individual units joined in a cumulative collective pattern.

he idea emerged out of his visit to Dogon communities in Africa, where single homesteads form a remarkable complex of a whole. What gave the project a remarkable sense of ‘unity in multiplicity’ was the use of repetitive individual domes. The ingenious idea in fact was not Van Eyck’s but of his assistant at that time, Joop van Stigt, who also adapted the scale of the interior of the building by reducing it to the dimensions of children. On the other hand, as opposed to the Amsterdam Playgrounds, which presented no functional problems, the ‘inventions’ of the Children’s Home remained symbolic gestures that rendered the building dysfunctional and eventually led to its abandonment.

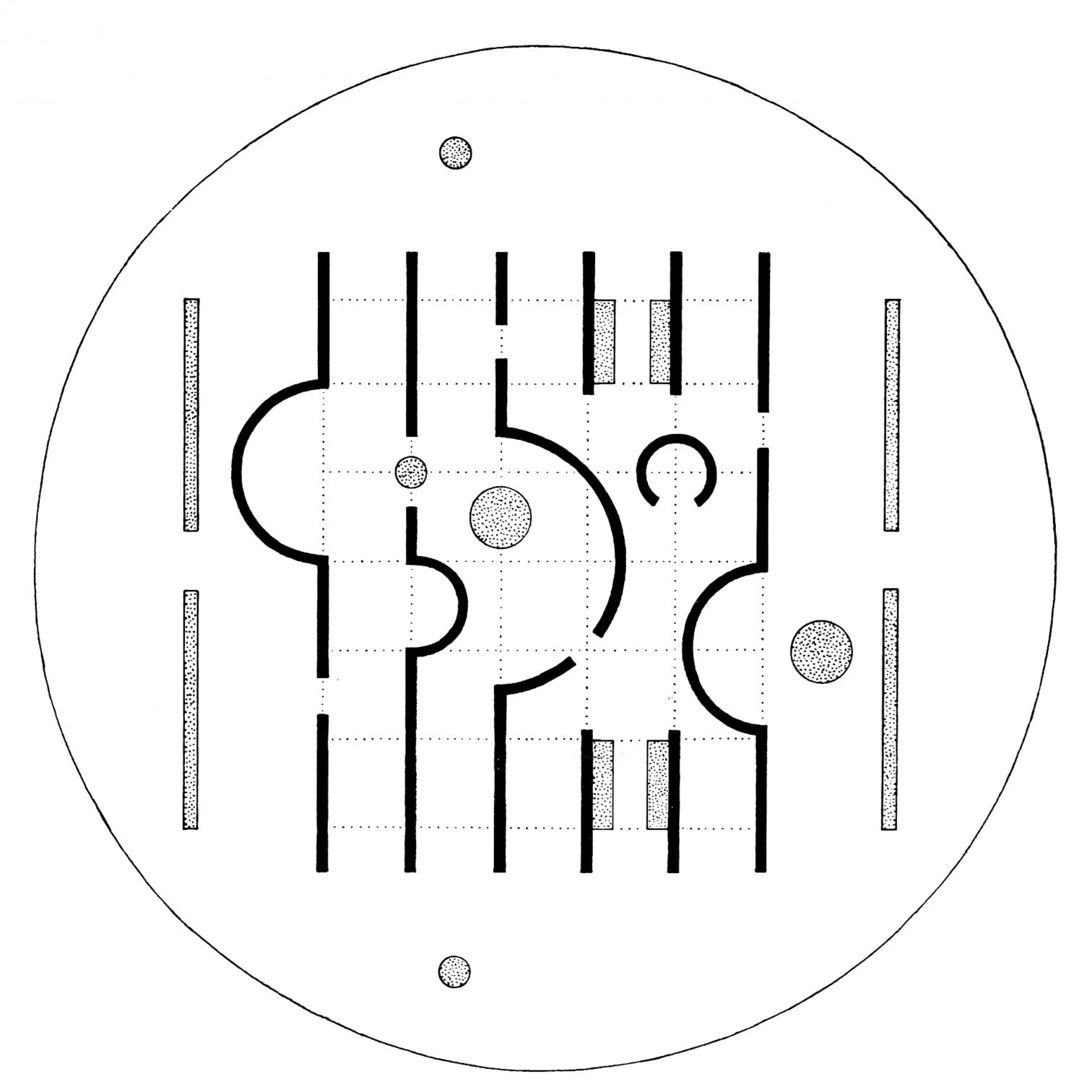

Later in life, a more experienced Van Eyck designed and constructed buildings which excelled equally as cultural manifestos and functional products. In 1965-66 he designed the Sonsbeek garden-pavilion in Arnhem, a shelter and a setting for outdoor sculpture exhibitions. The scheme looks like a twisted, ‘unloosenable’ knot, an endlessly branching out pattern, a succession of turnings and byways, a windowless building resembling a cave, a tangled combination of paths in which it is exceedingly hard to find one’s way, whether to penetrate to the center or, from there, reach the exit. A labyrinth with no declared terminal point, no treasure nor Minotaur, but where what one discovers – or rather unexpectedly rediscovers – is the wilderness of the mind and of the social cosmos when one comes face to face with the other. Van Eyck called it the ‘eureka effect’ or ‘aha! moment.’

Expresada ya en los más de 700 juegos infantiles proyectados por Van Eyck al inicio de su carrera, la voluntad lúdica y orgánica define sus obras mayores: la Casa de los niños en Ámsterdam y el Pabellón de Sonsbeek en Arnhem.

In an urban setting, too, Van Eyck tried to apply the idea of a ground-up incremental urban infill intervention in the existing city. He did this in the Hubertus House, in Amsterdam, a home for single mothers (now for single parents of either sex) and their children. Here the architect did not apply any of his games of juxtaposition and reconciliation of opposites. Instead, on the contrary, he resorted to a metaphorical image: in his own words, a “rainbow bouquet,” an “icon of joy, affection and optimism,” creating what he called a “sense of homecoming”; all through a paradox, making us feel momentarily like strangers in a new world ready for dialogue.

Liane Lefaivre is an emeritus professor at Vienna’s University of Applied Arts, and Alexander Tzonis, at TU Delft. They are the authors of Aldo van Eyck: Humanist Rebel (1999).