Design and Pedagogy

New Learning Environments

Educational Park, Marinilla (Colombia)

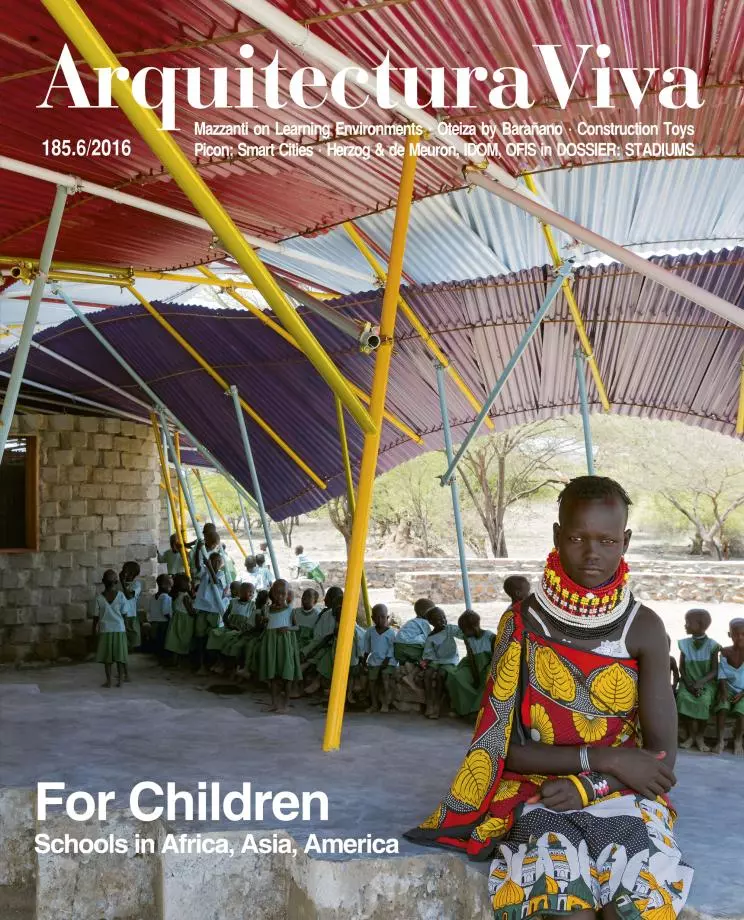

Architecture and design mark the difference in educational projects. Although this affirmation seems to state the obvious, it is not really so, because sometimes architects themselves don’t seem to be sure about their capacity to achieve what, referring back to the words of Cedric Price, we could call the socially beneficial ‘distortion’ of the environment. However, when we see the mechanisms of architecture applied to projects for children or young people included in the following pages (all of them in critical contexts), we understand the potential of design to improve the quality of life through interventions that are ‘modest’ in scale.

Analyzing these projects, most of which are located in what is classified as the ‘global south,’ can be a strategic opportunity to identify and transfer to new contexts solutions that, in a creative manner, procure maximum results with minimum resources. This transfer process is important and above all urgent, bearing in mind that the crisis also affects the so-called ‘first world’ (fast-paced migration flows, economic recession, and global warming).

This approach also calls to reinterpret the architect’s task. The design of memorable and even emotive educational spaces may involve socio-environmental transformation strategies. However, these strategies have the capacity to enrich and strengthen the communities when they manage to align with political initiatives, social programs, or consistent participatory processes. From this perspective, the notion of the architect as a lonely artist moves to the background and leaves way to that of architecture as a necessarily collaborative art. To achieve that adequate ‘distortion’ of context it is essential to articulate the participation of the many actors in the negotiation, a process in which the architect can often take the role of an entrepreneur in search of liaisons and opportunities. Hence, Beatriz Colomina’s invitation to consider architecture closer to a movie production than to the visual arts is still very tempting, and such approach entails examining as much the ‘end result’ as the production process.

Thinking of architecture as a mechanism for environmental transformation poses new challenges and, in the case of education, talking about ‘learning environments’ or about environments that allow ‘extracting’ the best of every one starts from a premise: that this process must extend beyond the classrooms, laboratories or reading rooms and invade our daily routines. It is not the same to ask oneself how to design a school, a kindergarten or a library than to ask oneself how to design a ‘learning environment.’ The first question evokes a specific architectural type; the second one invites to expand architecture’s reach and to establish an appropriate articulation with all the different actors involved in the process.

Designing educational environments means acknowledging that if architecture is the ‘third teacher’ and the environment an integral element of the educational experience – as Loris Malaguzzi suggests –, architects create not just objects and forms but can also develop additional skills to give rise to new behaviors. Rather than a container, architecture can itself be an educational mechanism: a tool with the potential to redefine how we learn.

Action and Communication

Architecture is able to express social and political projects effectively. The España Library, for instance, reflected Medellín’s effort to include marginal neighborhoods in urban life through architecture. The image of the library emerging from the mountains among small houses has become an important element of the area’s identity, as well as a city landmark.

But architecture has other no less important capacities: operational ones. Marinilla Educational Park, inaugurated this year within a broader program of the Antioquia Government, is at once a park, a pedestrian street, a domestic garden, and a learning infrastructure. Instead of developing a specific architectural program, the variety of actions deployed in the project proposes a landscape that opens up to event, to the unpredictable. That is why the design is not just to a matter of formal composition, but a performative issue. Like a game, the proposal prompts discovery and surprise in public life.

The Pinch Library and Community Center designed by Olivier Ottevaere and John Lin in Yunnan province, China, is an example of architecture’s visualization capacities. It was financed by the University of Hong Kong as part of the reconstruction efforts after the 2012 earthquake. The timber roof contains the library, but its accessible structure creates a play space, and its roof becomes a viewing platform. It’s all about layout: architecture does not determine the actions that will take place, but it has a wonderful capacity to favor, trigger (and limit) certain actions. This open architecture is in the end closer to contemporary art installations (which need an active user) than to modern sculptural pieces (requiring a passive observer).

These open projects in which architecture can serve several purposes make things difficult for ‘sustainability,’ an increasingly hackneyed term, mostly because of the ubiquity (and vacuity) of the automatic answers to which the building industry is making us grow accustomed to. The strategies to reduce the environmental footprint, developed in the field of bioclimatic architecture, are obviously positive, but their reach is limited if we leave out architecture’s capacity to promote and stimulate social life. From this point of view we can suggest some provocative elements, which could well be added to the vast repertoire of strengths of socio-environmentally sustainable architectures:

Modules and Systems

As an alternative to closed designs for a specific place or function, the development of open and adaptive systems based on association modules and patterns proposes buildings that are able to adjust to very different circumstances, be they topographical, urban, or programmatic. This approach generates structures that can grow, change, and adapt to circumstances and time, and take on many scales. Projects like Timayui or the modular systems for 21 kindergartens on the Colombian Atlantic reflect another way of working, where instead of designing distinctive forms, architecture organizes protocols and selfgenerative systems: an architecture that admits alterations, accidents, and exchanges, devised as a modular interplay rather than as a permanent structure, and whose value rests precisely on this capacity for change.

Multifunctional Platforms

The design of educational infrastructures is a perfect platform to test how the number of functions can increase beyond the initial architectural brief. Architecture contributes to social sustainability when it is able to multiply its functions by increasing the hours of use or the number of users initially foreseen. The coexistence of contradictory actions, the unfinished character, indefinition, and anomaly propose alternatives to the traditional idea of function as productive and univocal efficiency. These practices multiply the possibilities for change and adaptation, revalue public investment, and propose new ways of using the learning environments, undermining the idea of efficiency as the only driving force behind the modern architectural space.

The Value of Play

Play is an essential part of learning. Rethinking traditional school architecture of corridors and closed classrooms (an architecture based above all on functional efficiency and on Prussian educational models) through play can bring about new behaviors, events, and interactions. So conceived, the design of learning environments seeks to stimulate the creative capacity of users, so that situations like ‘skateboarding in a library,’ as Bernard Tschumi proposed, can actually happen. The value of play and anomaly resides in the construction of interaction moments able to foster human relationships that are different from those predetermined in the functional space. For those involved, playing in this way is significant because of the lessons learnt from sailing through the rules and traps, and because of the alteration of the moment lived. Besides, approaching play as a complex event is key to reflecting upon the value of the ‘void’ in the construction of social life and friendship, as well as the rise of affinities and disagreements within a learning community. We could say that in this program-less void we learn to ‘be-in-community.’

Learning ‘about’ and ‘in’ Context

Designing educational environments means that, through the experience of the built environment, a child should be able to learn. For instance, when building a school, the way in which materials are used can teach children concepts such as tall or short, soft and hard, dark and bright. A courtyard can help to understand how different materials heat up or cool down differently, or how they change in shape or color. Children can in this way learn ‘about’ and ‘in’ the environment. The courtyard, in this case, is not there just to fulfill the need of creating outdoor spaces, but also to organize an environment based on learning from experience. We can in this way talk about a school architecture that acts and contains, and about the creation of multisensory learning environments that draw on experience and multiplicity. An architecture, ultimately, that is defined by what it does, not by its appearance, and by what it prompts to do, not by what it looks like.