From Silence to Light

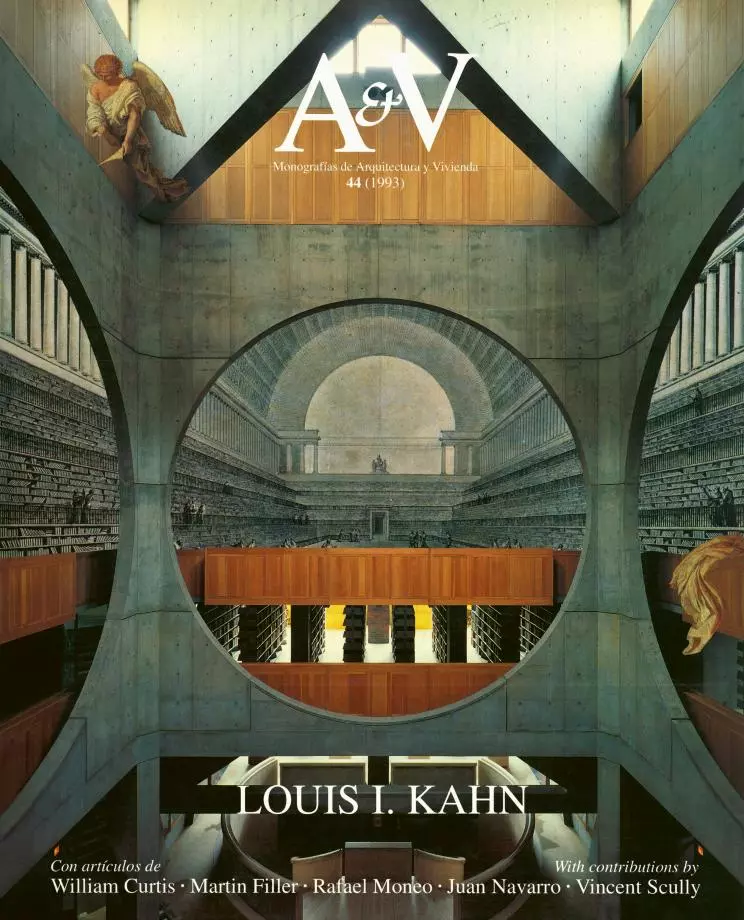

Architecture is made in two rooms. One does not exist in reality, yet a major part of the work occurs within it. In the other room, projects are carried out according to pertinent physical considerations. A work of architecture is a fusion or superposition of figures elaborated in both chambers. Through their image or likeness, this double origin of the works can be deduced. Therefore, when viewed analytically, a materially constructed room opens up and unfolds so that it can be related metaphorically and literally to the two primordial rooms.

Kahn examined this creative swaying and called its extremes ‘silence’ and ‘light’. All human production would be situated at certain thresholds of this chain of comings and goings from one to the other, from silence to light. In any case and in all works, the two states appear to be fused together. The silence and light of Kahn are basic, radical conditions. They are like a blank paper before it is written on, which is both desire and a means of expression. Art is situated in a place close to silence. The artist addresses an individual impulse for expression while responding to natural demands, to the elemental physical laws that allow a work to be incorporated into the world.

All in all, the artistic medium is a variable collective spirit and a variable repertoire of physical articulations of materials, colors, and sounds. Le Corbusier’s L ’Esprit Nouveau pavilion and Mies’s Barcelona pavilion are unfoldable rooms which refract into extreme chambers, well structured and well defined. They are forceful objects, exponents of the means of expression and production on one hand, and also of the urgency of expression, of a collective artistic state and an emerging imaginary universe.

Because of this dual constitution, specific works are prolonged in a continuum that penetrates into a collective impulse and a natural order. Every design emerges and takes root in an imaginary room, which is open and ever changing; at the same time it seeks the approval of the laws of nature and extends into the natural medium. It is against this double background that all the particular figures take shape. Upon immersing a hand inflowing water, whirlpools are felt and the movement of the water becomes evident. At that moment there is a double revelation: our desire to experience and express the nature of water and of its previously unnoticed flow. The Chinese dragon is a mythical image of power, a paradoxical figure of the infinite, a figure made of the same substance as the background, a pleat of air or water. It incorporates itself into the realm of visible and graspable things, but its nature is incommensurable.

Silence and light, form and design, the measurable and the incommensurable: these are notions painstakingly worked out by Kahn in his desire to capture the creative process. Upon examining his work we deduce the place they occupy in an extensive fabric that penetrates the visible and the invisible. Natural order, geometrical order and number, strategic or generic normative obligations show that they belong to a continuous background rich in dimensions. The Form and shapes come together in a connecting line of topological invariants or prototypes. The Form is an ideogram and the shapes refer us to a writing in hieroglyphics.

Likewise, time and the guidelines of its taking over of space are seen as the basis of ornament. Kahn understood ornament as an expression of method: regulated time, linked to the moment when the pencil draws a line associated with the joint of the concrete in the building being designed.

Throughout his life he paved the path for a penetrating and introspective intellectual process, articulating and setting radical conditions in the most distant points of the creative course. Kahn worked arduously in a room where architecture did not yet exist.