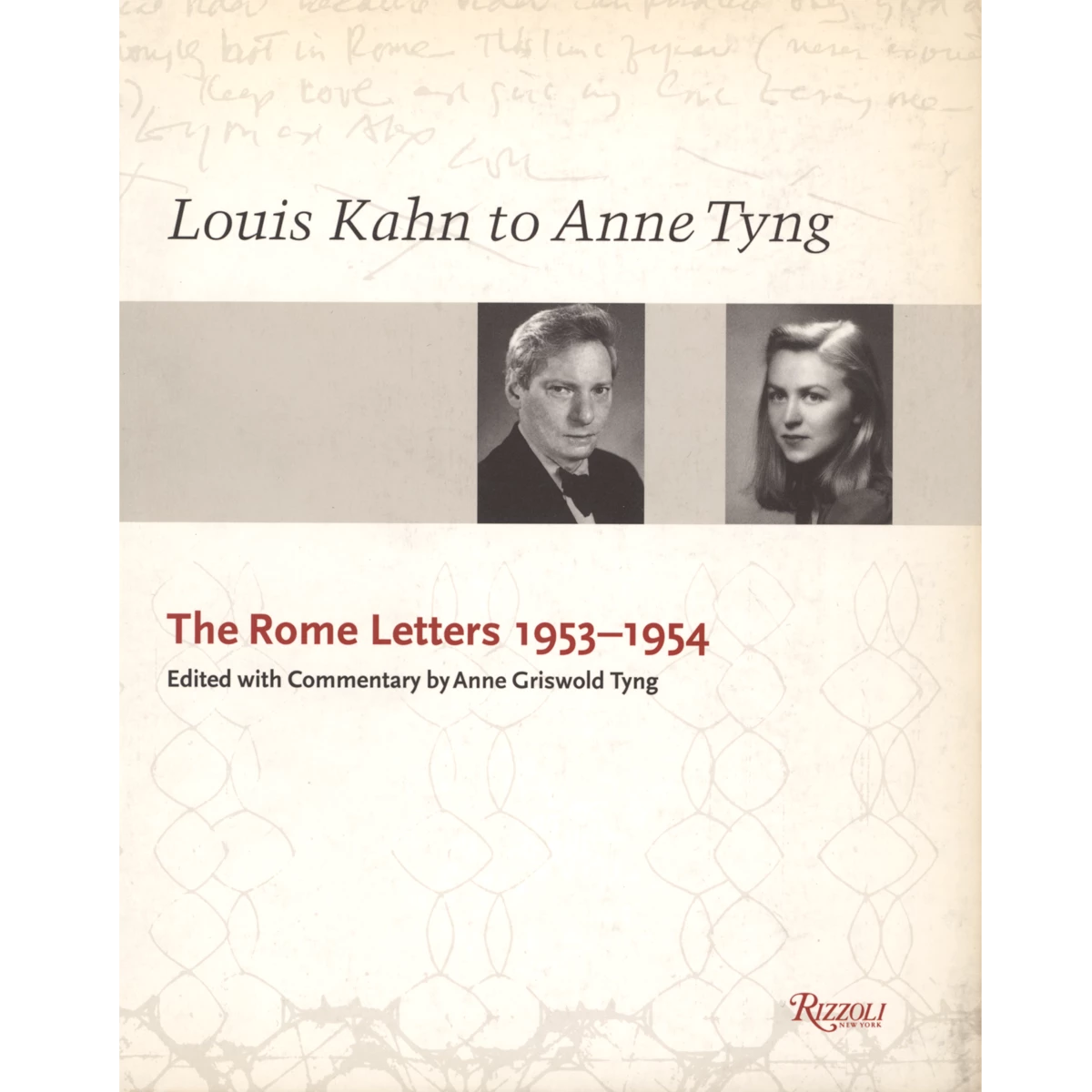

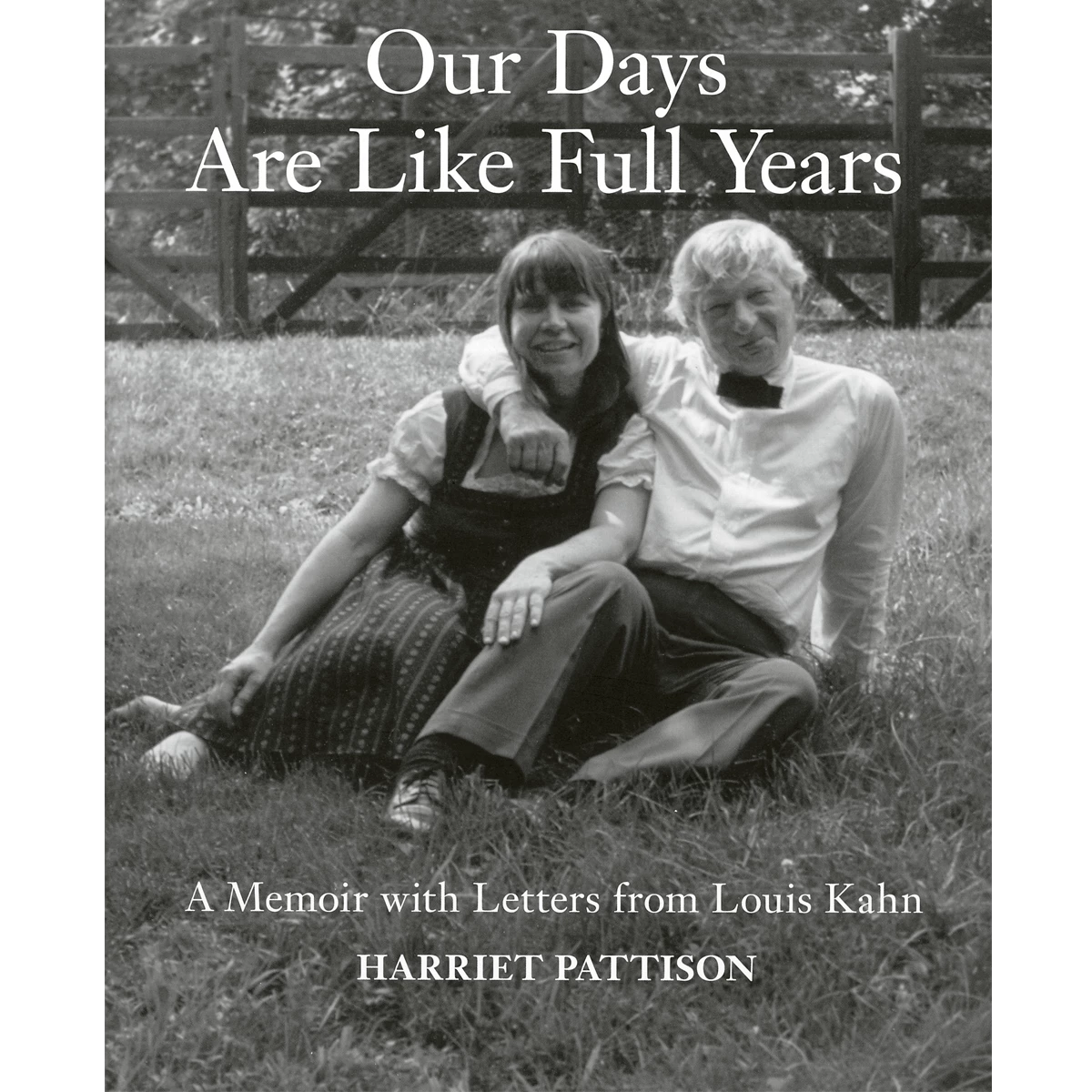

Aphoristic in his teachings, Louis Kahn was torrential in his letters. Those he wrote to Anne Tyng, his collaborator and lover, mother of his daughter Alexandra, were published in 1997 under a title (The Rome Letters 1953-1954) that alludes to the time she left for Italy to give birth far from Kahn, who was married to and economically dependent on his wife, Esther, mother of his first daughter, Sue Ann. For their part, the postcards and missives sent to Harriet Pattison in the period between the start of their romance in 1959 to Kahn’s death in 1974 are seeing the light now, with the melancholy title Our Days Are Like Full Years, interspersed with her own memories, where a special part is played by their son, Nathaniel, who in 2003 would pay tribute to his father through the endearing documentary My Architect.

Anne Tyng, whose centenary we celebrated in Arquitectura Viva 224, was an architect of great talent who brought into the practice of Kahn – then still undecided between his Beaux-Arts training and the International Style of his housing projects – structural and geometrical concepts without which the Yale Art Gallery, the Trenton Bath House, or the City Tower scheme would not be understandable. When she published his letters, it was also an apologia pro vita sua, for after 19 years in the office and 15 of sentimental attachment, Kahn forced her to leave the firm by giving her no work to do, and even trying to deny her credit in projects they had signed together. But Tyng always rejected the role of muse, “a shadow figure, an empty vessel,” and claimed the recognition that history has ultimately given her.

Very different is the book released by Harriet Pattison, whose relationship with Kahn was one of devout subordination. Like Tyng, she was excluded from festive events or the architect’s funeral, but her case was worse, reduced to the status of intermittent lover, even though her love of gardens eventually gave her landscaping credentials and the chance to collaborate in some late projects, such as the Kimbell or the FDR Memorial. Very insecure yet capable of standing up to her own family, which in view of the shame of pregnancy tried to make her choose between abortion, adoption, or a marriage of convenience (even to Bob Venturi, her first boyfriend), Pattison admired Tyng’s determination and talent, and their respective children, siblings after all, became close. In the story also appears another lover of Kahn, the architect Marie Kuo; or the Catalan Carles Vallhonrat, the master’s right-hand man in the 1960s and founder of his archive, where Tyng’s and Pattison’s letters to him, absent in these books, are perhaps kept.

At the start of her warm and elegant account – splendidly illustrated with drawings, photographs, and facsimiles of correspondence – Pattison fears becoming an Edith Wharton character, “the lover of a man who showed up at his convenience, living in the quiet desperation of an unkind city”; and at the end, in the wake of Kahn’s death, unemployed and nearly penniless, she feels cast into the shadows “like a Chekhov character banished to the provinces.” Between Wharton and Chekhov, Nathaniel Kahn’s mother has left us a testimony that is as moving as the documentary of her son.