The critical intelligence of Diller Scofidio + Renfro is expressed through a lyrical language. Though in the first installations and videos of Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio – from Para-site in 1989 at the MoMA to Overexposed in 1995 at the Getty Center – vision underwent an abrasive scrutiny, their view of the world was already both analytical and poetic, as the never built Slow House rhetorically sums up. In 1997 Charles Renfro joined an office that with the turn of the century moved from concept to construction, with works as influential as The Blur pavilion on Lake Neuchâtel, finished in 2002, or The High Line in New York, whose different sections have been completed over the course of the past two decades. At the same time, the commissions of Boston’s ICA and of the renovation of The Juilliard School at Lincoln Center, both in 2003, brought a change in scale that led to strengthening the team in 2004 with a new member who would become the fourth partner, Benjamin Gilmartin.

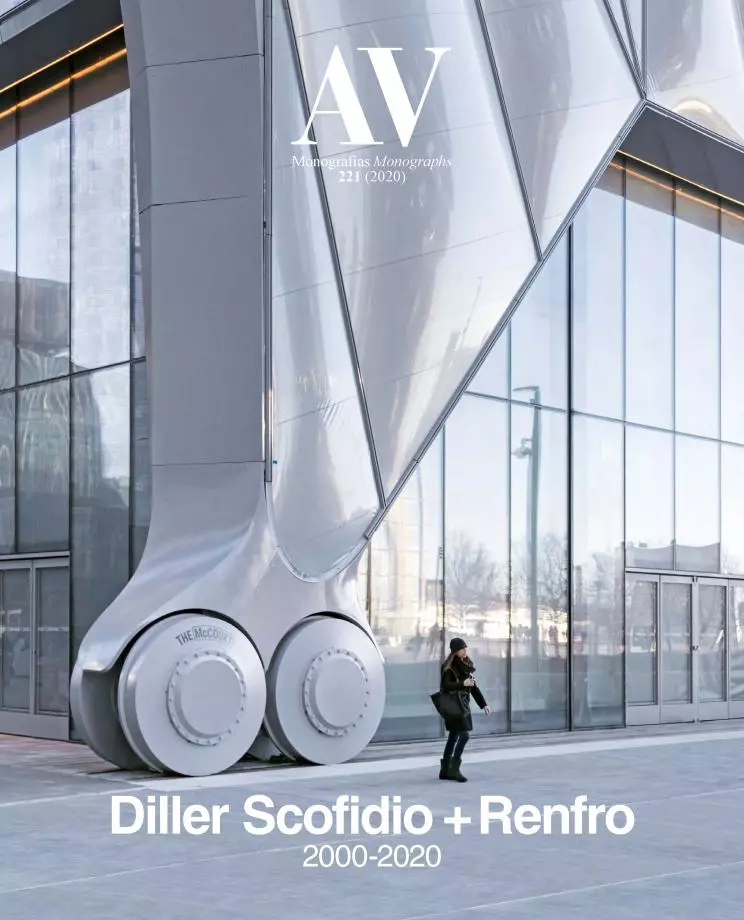

This formidable process of growth, which has taken the studio to build in Brazil, Russia, Great Britain, and China, has also materialized with works on both coasts of the United States, from Los Angeles, Berkeley or Palo Alto to Providence and, of course, New York – their professional, personal, and academic base –, where in 2019 they have inaugurated the last stretch of the mythical High Line, the impressive center The Shed, and the colossal extension of the Museum of Modern Art, rounding off a year of unique achievements and visibility. But perhaps what is most important about this growth, which in thirty years has led these intellectual artists from exhibiting at the MoMA to building it, is that in the process their critical edge has been tempered by the pragmatism of a large office, without affecting their visual talent or their poetic drive, which still draw on the atmospheric appeal of the Swiss lake pavilion or the wild beauty of the elevated New York park, joining mist and nature through geometry.

Trying to orchestrate their prolific production since 2000, here we propose a triptych of interests, strengths, and intentions, introducing each section with an installation that shows the vigor and resilience of their critical project: the desire to create new landscapes, introduced by ‘American Lawn,’ their splendid exhibition at the Canadian Centre for Architecture of Montreal, which unveils the meaning of a botanical artifice present in both the private realm and in public space; the determination to make knowledge visible, evident in many of their projects for education, and masterly expressed in Exit, the installation on demographic movements inaugurated at the Fondation Cartier in Paris and shown later at several other venues; and the goal of making the arts accessible to broader audiences, pursued in their many museum projects, and expressed with unique emotion in the extraordinary and ephemeral Mile-Long Opera, which brought 1,000 singers to the High Line for six nights during a lyrical autumn.