Louvre Museum, Abu Dhabi

Shape of Arabesques- Architect Jean Nouvel

- Type Culture / Leisure Museum

- Material Steel Aluminum

- Date 2018

- City Abu Dabhi

- Country United Arab Emirates

- Photograph Fatima Al Shamsi Abu Dhabi Tourism & Culture Authority Mohamed Somji

Oliver Wainwright

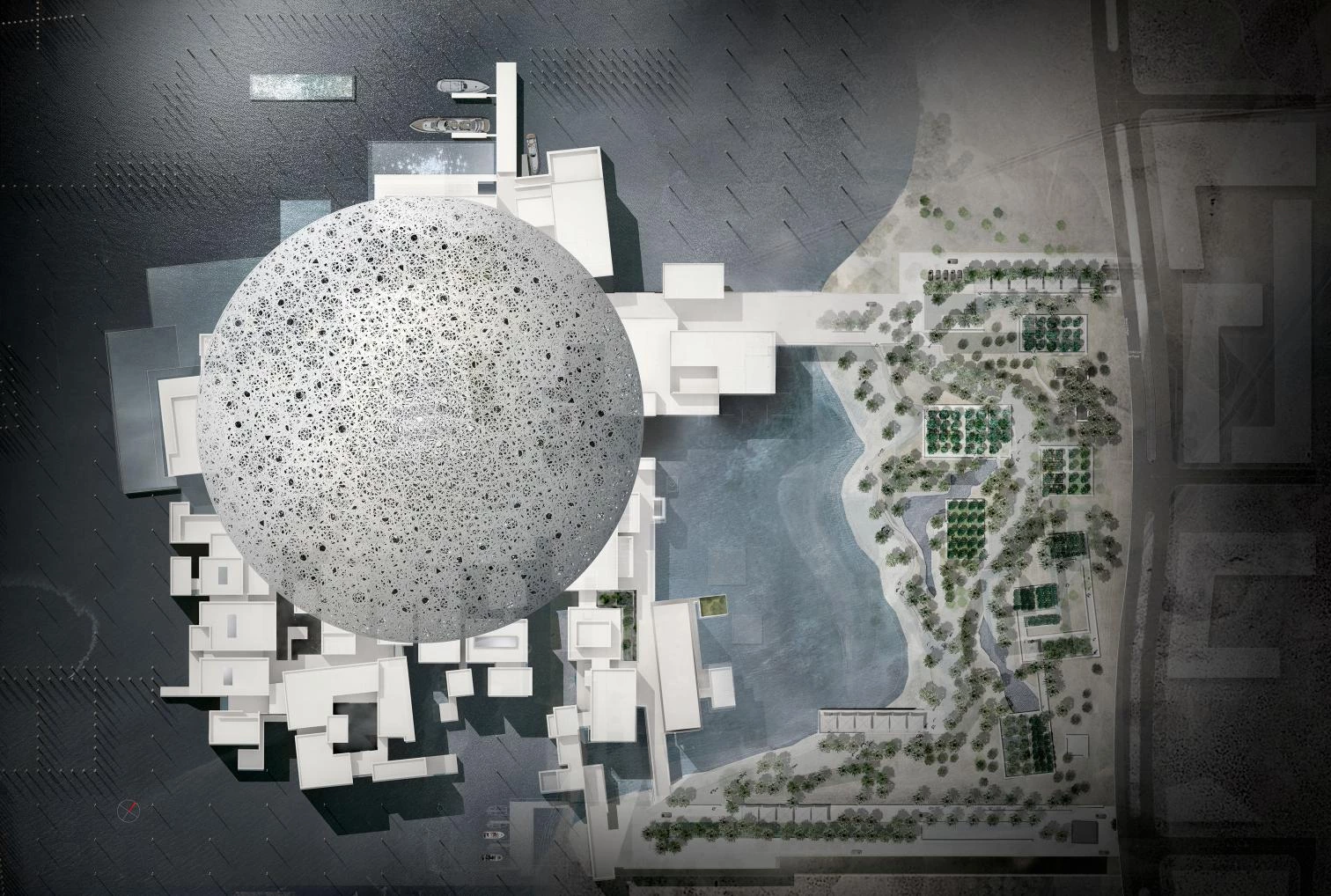

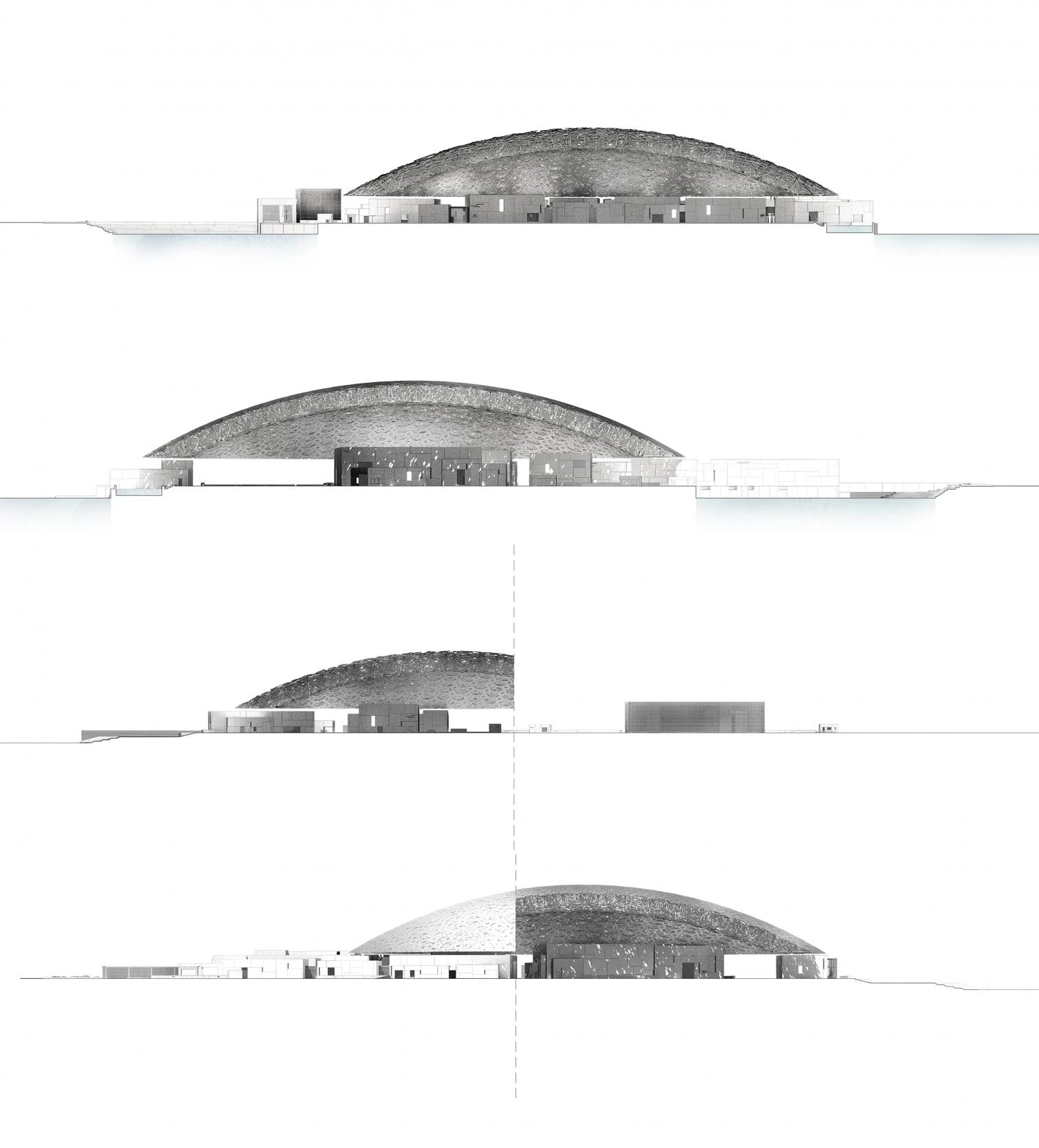

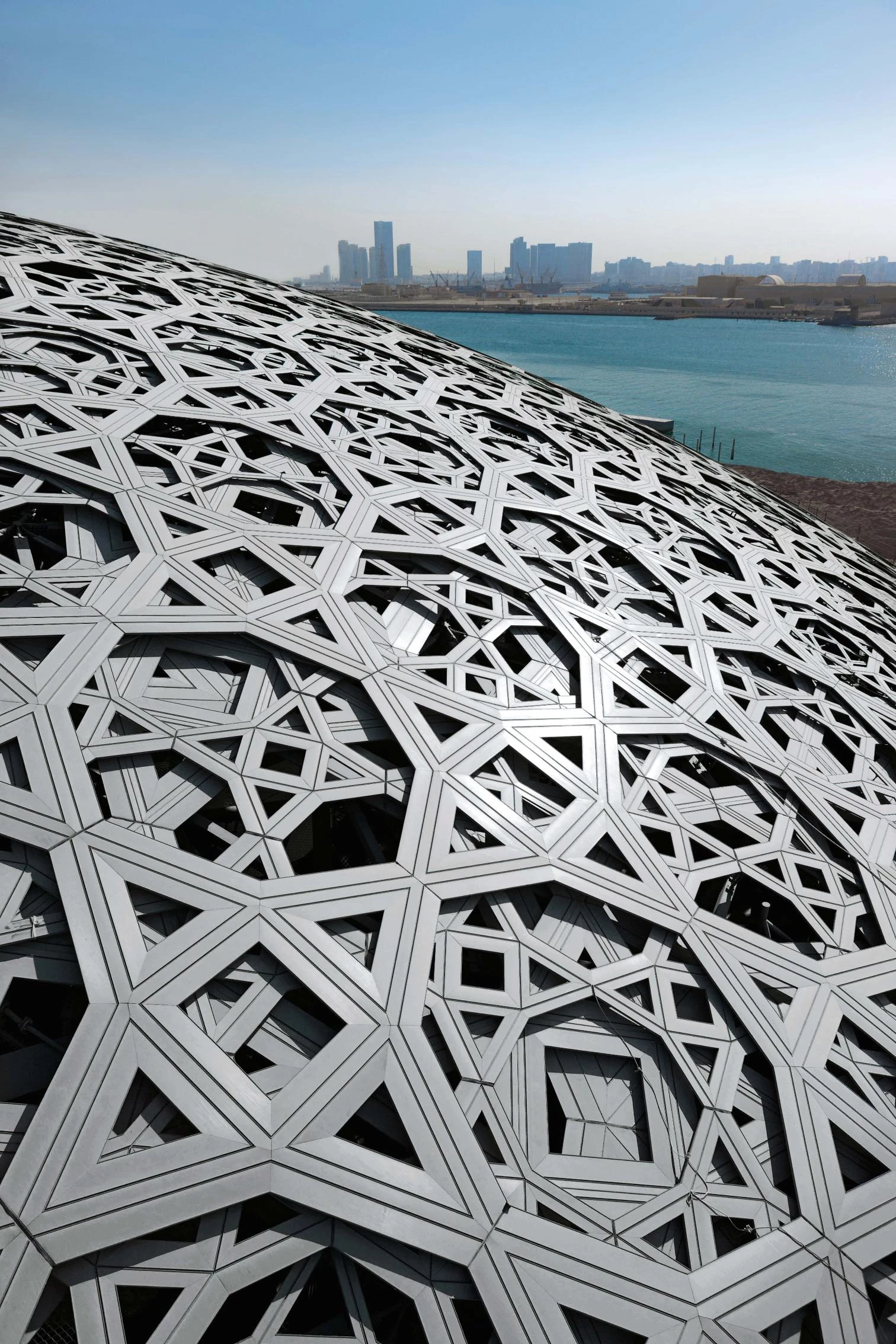

Hovering above the sandy shores of Saadiyat Island like an upturned colander washed up on the beach, the metal-domed roof of the Louvre Abu Dhabi doesn't give much away from the outside. A cluster of white blocks spreads out from beneath the great cupola like scattered sugar cubes, forming little streets and squares, like a village in the desert. And compared with the garish mirror-glass towers of the city's seafront corniche across the water, this multimillion-pound palace of culture seems modest.

"I wanted to create a neighbourhood of art, rather than a building," says Jean Nouvel, the French architect of the new Louvre, which opened to the public on 11 November, and enjoys the use of the venerable Parisian institution's name in a 30-year deal worth over £663m - a first for a museum outside France.

"It is conceived as something between an Arab medina and a Greek agora, a place to meet and talk about art and life in total serenity." Standing beneath his vast cosmic dome, with rays of light piercing through its layers of star-shaped latticework, casting dapples across the facades of the white concrete buildings, you feel transported to another realm.

Water laps at the base of the stone platform, flowing beneath the canopy in reflecting pools that cool the air and bounce ripples of light back into the space. Architects are fond of talking of painting with light. Here it rings true. The effect is mesmerising.

Inside, works by Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko hang a few steps away from others by Henri Matisse and Vincent van Gogh. Highlights include a Grecian sphinx from the 6th century BC, Leonardo da Vinci's Portrait of an Unknown Woman, and Ai Weiwei's crystal-encrusted recreation of Tatlin’s Tower, which could have been plucked from the ceiling of an Emirati palace.

The Prestige of Culture

The Louvre Abu Dhabi is the first completed building in the oil-rich emirate’s long-delayed $18 billion plan for a cultural island, dreamed up over a decade ago in the days before the global financial crisis.

It was to be a prestige destination, aimed at luring visitors with cultural cachet, in the continuing competition with its more glamorous neighbour, Dubai. Alongside the acres of luxury villas and golf courses (which were the first things to be built), there was to be a gargantuan new Guggenheim Museum by Frank Gehry, seven times the size of its New York home, designed as a topsy-turvy heap of cones.

The program is distributed in a total of 55 pavilions the size of a room, placed on sheets of water and built with white concrete; set over them is the dome whose powergul exterior image characterizes the museum.

It was to be joined by the Sheikh Zayed National Museum by Norman Foster, in the shape of a racing falcon's wing (for the sheikh's favourite pastime); a maritime museum by Tadao Ando, as an angular vault rising out of the sea; and a performing arts centre by Zaha Hadid, modelled on a writhing tangle of ectoplasm. None of these has yet broken ground.

"It can be catastrophic when buildings are parachuted in by international offices, without any roots in a place," says Nouvel, whose design was the most refined of this supercharged architectural petting zoo. He knew his high-octane neighbours would rise to over 80 metres, so he wanted to hunker down and speak more softly; his dome floats less than 30 metres above the shore. "We must always be sensitive and contextual, even where there is no apparent context," he adds, describing finding an empty patch of sand when he first visited by helicopter, long before there was a bridge to the mainland.

Medina for Art

His starting point of a loose-fit medina was a canny response to the vaguest of briefs, which came out of the blue, without specifics. "A classical museum of civilisation," is what the sheikh asked for in 2006, before the Louvre had been identified as the preferred partner to fill the building’s halls. But the built-in flexibility has had the benefit of making a place that feels like a historic museum that might have grown organically over time, as if taking over existing spaces that have been adapted and retrofitted.

Comprised of 55 room-sized buildings, organised in a carefully organised jumble, no two galleries are alike. Ceiling heights vary from the intimate to the lofty, materials range from dark bronze to silvery marble, while atmospheres oscillate from the sepulchral to the light-flooded, depending on whether it is Qur'ans or Mondrians on display.

The as-found quality extends into the sea too, where random rows of mooring posts rise out of the water like ruins of something that once stood here - or the foundations for an expansion to come. In a James Bond-ish touch, VIP guests will arrive by boat, gliding in to dock beneath the sparkling dome.

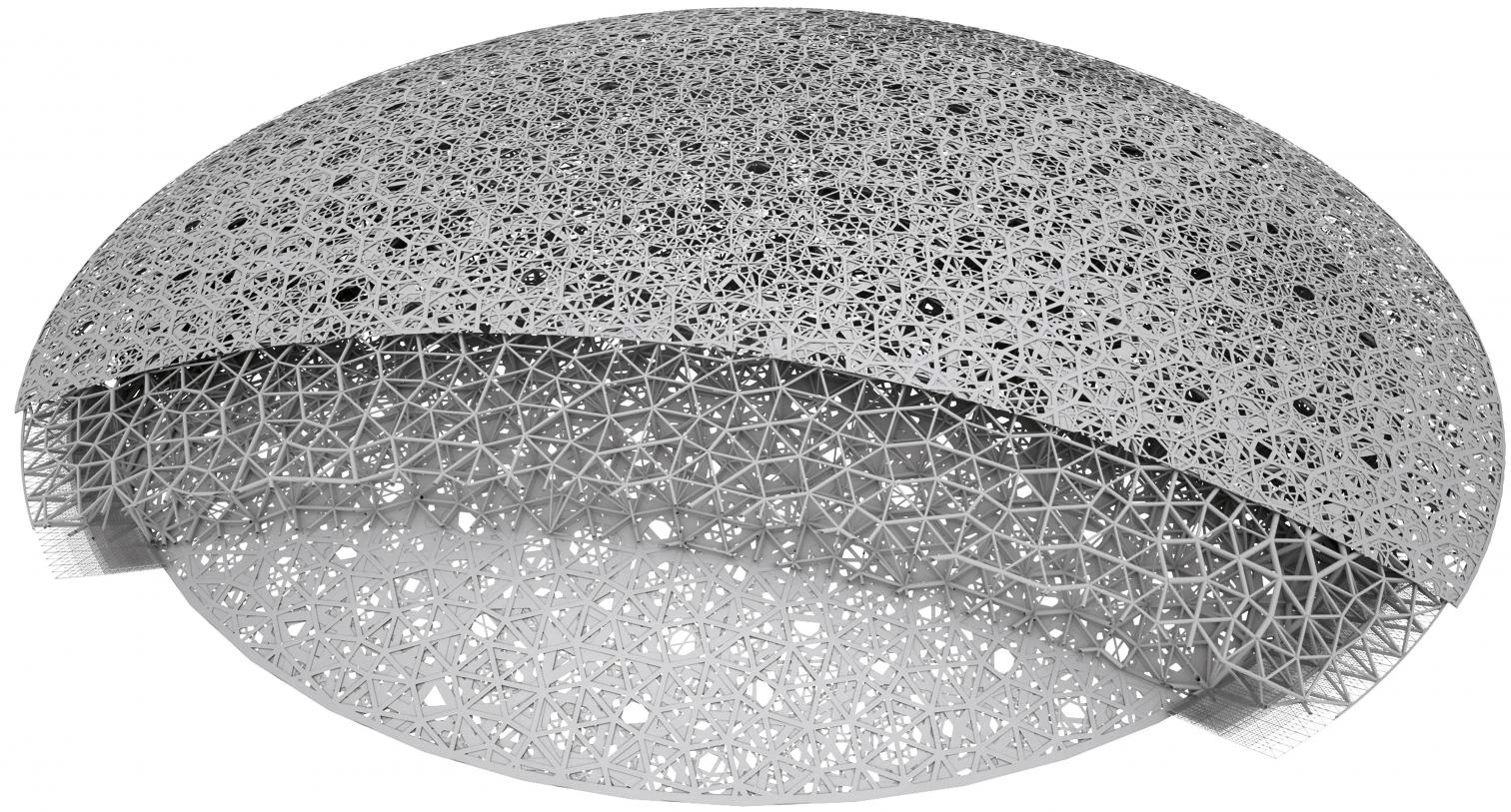

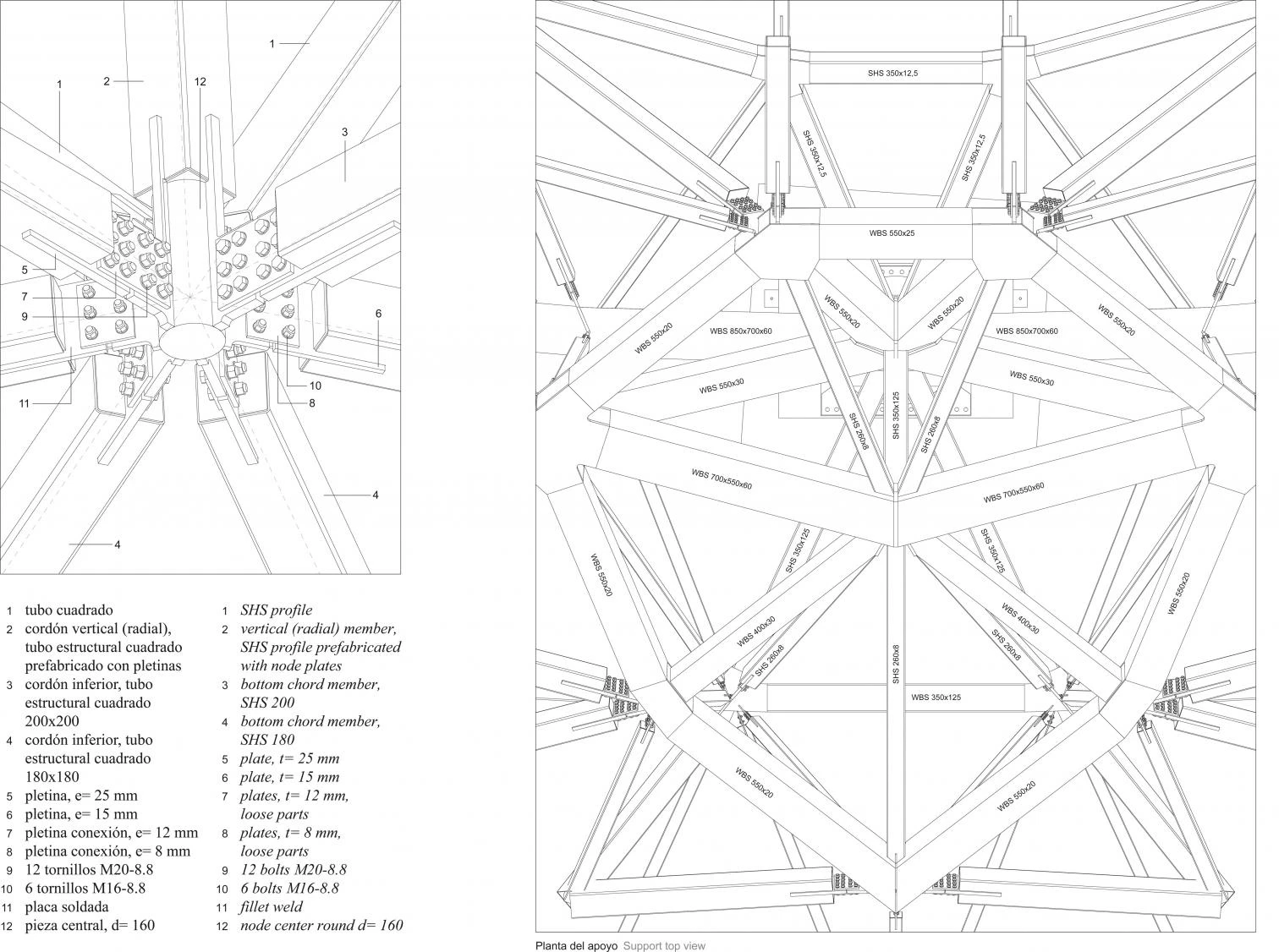

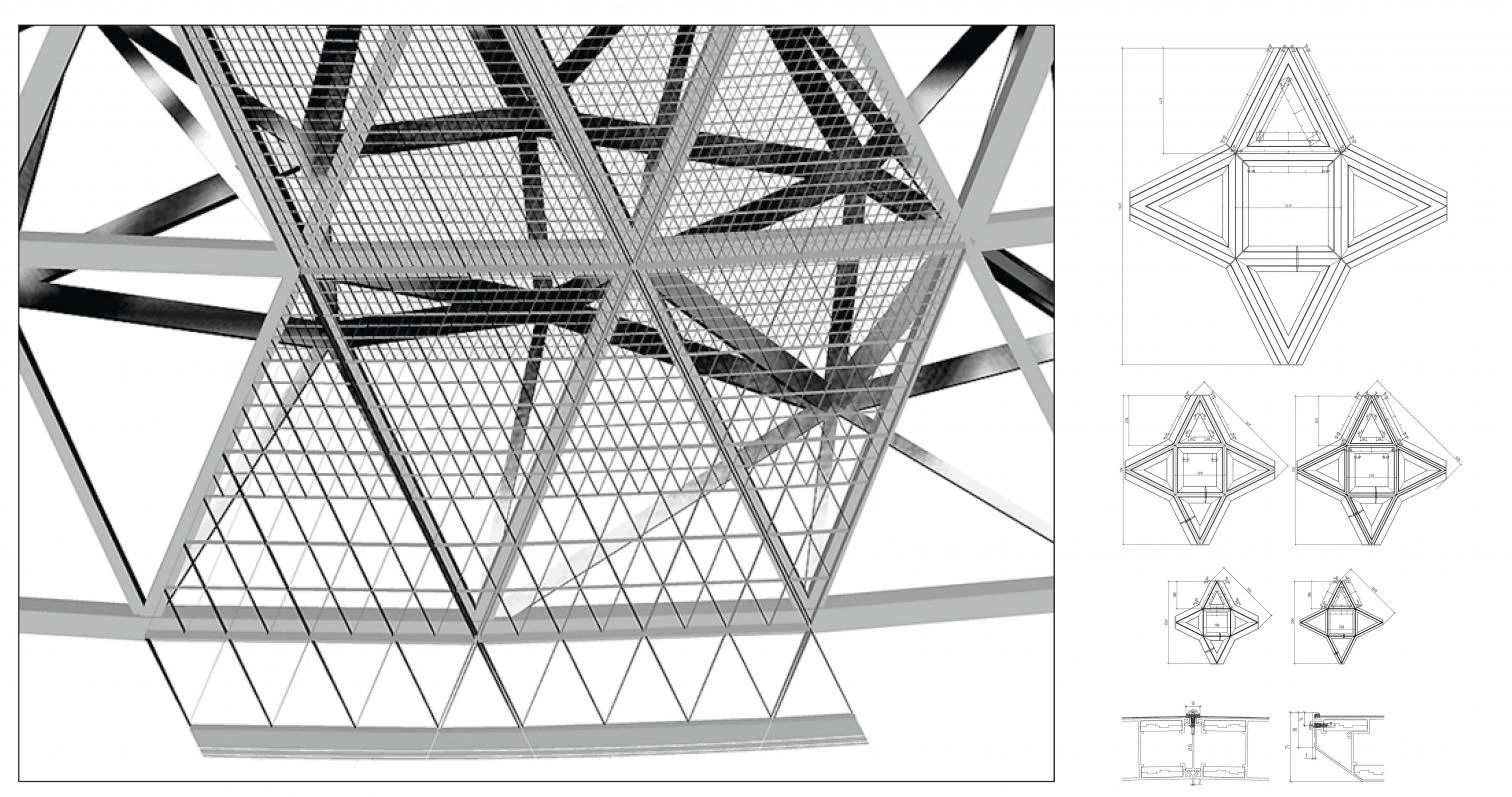

The enormous dome, with a diameter of 180 meters, is formed by eight layers of lattices that filter incoming daylight, generating variable effects, and it rests on four points hidden in the exhibition pavilions.

There is an air of 'sheikh chic' to it all and, in places, it feels like they had too much money to spend. Nouvel had the luxury of designing everything in sight, from leather furniture to light fittings, and some finishes betray his penchant for a touch of bling.

Light filters into the galleries through glass ceiling panels moulded in 17 patterns; each room has its own 'stone carpet', mined from a different exotic part of the world and inlaid with bronze edging. It verges on the tacky, although by the standards of petrodollar glitz familiar to the region it is a model of restraint. In one surreal moment, it looks as though the architect has gone full Art Déco, until you realise you have entered newspaper magnate Lord Rothermere's 1920s apartment, transported from the Champs Élysées.

The Paradigm of the Artifact

As a "universal museum for the 21st century", the galleries take visitors on a global journey through 12 chapters, arranged from prehistory to the present day; a radical hang intended to reveal threads between cultures and regions through the ages.

"It is the first time we not only have the decompartmentalisation of museum departments, but a means of reflecting on unexpected dialogues between artefacts," says Jean-François Charnier, scientific director of Agence France-Museums , the organisation charged with coordinating the 300 loans from 13 French museums, which will decrease over time as the museum builds up its own collection.

The cladding of the Louvre Abu Dhabi museum's dome involves 7,850 aluminum stars of different sizes, arranged in four inner layers and as may outer ones; in the latter, the pieces are coated with steel.

The alliance makes a fitting partnership, given that Abu Dhabi is about as old as the Louvre itself - the Bani Yas Bedouins settled here in the 1790s, as the museum opened its doors in Paris - but an unsettling undercurrent remains, with a sense that some things haven't moved on. Outside the press opening, south Asian construction workers put finishing touches to the landscaping in scorching midday sun, a reminder of the controversy over working conditions that has dogged the project from the outset.

A 2015 Human Rights Watch report found that, despite the construction of a spotless workers' village, many labourers on the Louvre project were still being kept in conditions akin to indentured servitude, forced to work for months without pay until their illegal recruitment fees were repaid, and subject to summary arrest and deportation if they complained.

"See humanity in a new light," trumpets the billboards leading to the new Louvre, and that is what this project forces you to do. Like many of the priceless objects on show, commissioned by despots and dictators throughout the ages, the nature of how the building was made is all part of the story, a troubling facet to this spectacular cultural artefact of our time.

Oliver Wainwright is the architecture critic of the British newspaper The Guardian, where this text first appeared.

Obra Work

Museo Louvre Abu Dabi, Emiratos Árabes Unidos Louvre Museum Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Arquitectos Architects

Ateliers Jean Nouvel

Fotos Photos

Fatima Al Shamsi, Abu Dhabi Tourism & Culture Authority, Mohamed Somji, Roland Halbe, Danica O. Kus