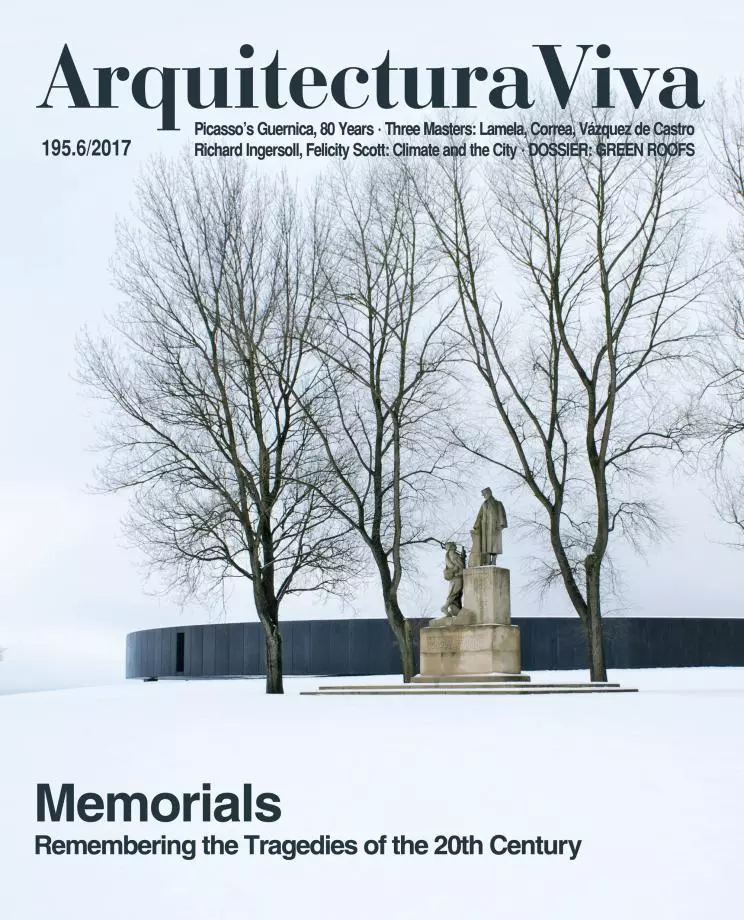

The Past is Never Dead

Memory and Memorials in Modernity

If the past is never dead (if, as Faulkner wrote, its continuity is the only certainty against the chimera of the future and the evanescence of the present), then monuments are redundances, yet since time inmemorial (suffice it to mention the Egyptian pyramids) leaving mementos of the past has been one of the greatest obsessions of humankind. Still, architecture’s powerful old commemorative function has been fading, to the point of becoming a rarity.

The reason for this is that the meaning of monuments has changed. Superstitious reverence to history is bygone. We regard them no longer as commemorative artifacts, but as objects whose value rests on their very antiquity; a change of perspective that Alois Riegl knew to detect back in 1902: “When we speak of modern cult of monuments or historic preservation, and the preservation of monuments, we rarely have deliberate monuments in mind. Rather, we think of artistic and historical monuments.” Added to such mutation of meaning is the bad press that the monument had among the moderns, who looked upon it as the materialization of the patriotically inclined rhetoric of the 19th century (the rhetoric of the arch of triumph or of the statue of the eminent citizen) and the sum of the evils of eclecticism, including excess in size or language and empty solemnity, which the iconoclasm and the ‘less is more’ tone of the so-called International Style endeavored to oppose. In this way, the ‘monumental’ was progressively pushed away from the discipline, becoming a thing of anachronistic or conservative architects, when not of outright fascist or Nazi ones.

Threatened during the dark years of the avant-gardes, the monument took a turn for the better when the apologists of modernity realized that to vituperate the past was to sacrifice something very important: it was a renouncement of architecture’s symbolic power. In 1943 Sigfried Giedion prophesied that in order not to succumb to that substitute for the civic that sporting events were, modernity had to create a new kind of monumentality, one which could express the values of community life and “pass them on to succeeding generations,” without falling back on old rhetorical vices. Incapable of offering some contemporary example of such civic monumentality, Giedion had no choice but to search in the Zeitgeist, the ‘spirit of the times,’ the same one that was then blowing and stoking up the flame of war and which, in the Swiss historian’s view, had materialized in Picasso’s Guernica, a work in whose terribilità he found the password of a new monumental language, conceived, like the old one, to ‘incite fear.’

Time proved Giedion right in the sense that, more than as civic celebrations, modern monuments have served as tragic symbols of their epoch, reviving an age-old function, perhaps architecture’s primordial one: remembering the dead. This return to origins has involved transformations in both the ideology that justifies monuments and in the forms used to raise them. Ideological transformations have affected what are remembered, which are no longer the achievements of a monarch, a hero, or a notable citizen, but the wars, genocides, and other barbarities instigated by the anonymous but powerful machineries of the banality of evil. For their part, formal changes have injected the monument with strategies that are the stuff of contemporary art and with aesthetic categories of a romantic bent, such as the picturesque or the sublime, in principle far removed from the language of this building type (the monumentum was always classical) but useful for evoking character. The consequence of all this is that funerary monuments, the only feasible alternative for the old celebratory monument, have become a modern type on their own right.

White Crosses, Green Hills

The history of modern memorials begins with the first massacre of the 20th century, the Great War which left 20 million dead in the fields of the European continent. On these fields, horribly disfigured by the explosions of thousands of shells, the winning powers raised an infinity of ‘monuments to the fallen’ or the ‘unknown soldier,’ from 1920 onward, as a way to remind the world of the terrible sacrifice of lives. The most refined among these were those designed by Edwin Lutyens, which, though late examples of eclecticism, adopted strategies suggesting a new, different kind of sensitivity.

A case in point is the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing, on the site of the Battle of the Somme, which is traditional in that it takes the form of a large triumphal arch, punctuates a long compositional axis, and presents the conventional iconography associated with the funerary (the temple, the pyramid, the cross, the flame), but novel in that it is free of pompous rhetoric, thanks to the manner in which Lutyens controls scale. So the triumphal arch and the symmetrical pavilions were not ends in themselves, but ways of marking the vast meadow they were built on, accompanied by another motif that would be oft repeated in later memorials: the abstract field of white crosses. Completing the funeral repertoire is the exquisite attention that Lutyens pays to the inscription, a traditional element of the classical monument but reinterpreted by printing the names of the fallen (72,246), one after another, on a gigantic plaque of marble that covers a plinth of modest scale; an inscription impossible to grasp in its totality but which, precisely because it is incommensurable, strikes a sublimely disturbing chord on account of the sheer magnitude of the tragedy the building commemorates.

Less about patriotic victories than about anonymous massacres, the memorials of Lutyens were forebears of constructions devoted to other, subsequent wars – of both the very representational and partisan kind (suffice it to name the Valle de los Caídos in San Lorenzo de El Escorial) and the more abstract and decorous type exemplified by the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial overlooking Omaha Beach, dedicated to all those who perished in the Allied invasion of the French north coast, or the Arlington National Cemetery across the Potomac River from Washginton, D.C., to the casualties of all the wars fought by the United States in the course of the 20th century. In both these cases, eclecticism gives way to an exacerbated picturesqueness that results from the opposition between white crosses and green hills, and which is complemented by the at once sublime and ‘minimalist’ motif of the cross repeated practically as far as the eye can see, up to the horizon.

The memorials at Thiepval, Omaha Beach, and Arlington honor those who perished in the two world wars by means of electic variations of a picturesque motif: that of white crosses and green fields.

Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia (USA)

Theaters of Memory

The German philosopher and sociologist Theodor W. Adorno said, “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” This declaration could well apply to monuments built in memory of the most cruel acts committed during World War II: nuclear destruction and the Holocaust. How can the memory of something unspeakable be given posterity? What is the right vocabulary and tone to use for the inexpressible?

One of the first responses was the Monument to the Fosse Ardeatine’s Martyrs, which commemorates the killing of 335 Italian civilians by German occupation troops, outside Rome, on 24 March 1944. It was built in 1949 by a young team committed to modernity (Giuseppe Perugini, Nello Aprile, and Mario Fiorentini, in collaboration with the sculptors Mirko Basaldella and Francesco Coccia) but able to reinterpret tradition while capitalizing on the symbolic power of the location: the quarry where the terrible events actually happened. The effect of this monument is created by a series of overwhelming atmospheres which give the visitor varied corporeal experiences along a route that starts within the quarry and ends at a group of sculptures, passing through the complex’s most powerful feature: the mausoleum, covered by a huge slab of concrete – conceived like the lid of a sepulcher – which in separating from the ground forms a dramatic crack around the edge, letting light seep in, besides protecting the 335 identical tombs carpeting the sloping ground. Like the memorials of white crosses and green hills, the Monument to the Fosse Ardeatine’s Martyrs appropriates the exact spot of the tragedy, but with a much higher degree of abstraction, in a treble clef that is picturesque (the cave motif), sublime (the gravitas of the funereal atmosphere), and minimalist (the graves of raw stone arranged in series and personalized by inscriptions).

A similar fusion of the picturesque, sublime, and minimalist is discerned in evocations of other ‘unspeakable’ events. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial, which recalls how 140,000 people were killed by the atomic bomb on 6 August 1945, is perhaps the best known example of a category of monuments, that of theaters of memory, which are based on the partial or total preservation of the scene of the tragedy. Preserved in this case are what were left of the Genbaku Dome, located right at the epicenter of the explosion, and the remains are activated by means of a sublime sentiment invoked no longer by confirmation of the destructive power of time – as in the olden days, when ancient ruins were contemplated – but by the boundless power of technological war.

Very similar is the strategy followed in an even more ominous place: the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, scene of the industrialized annihilation of a million people. Here the theater of memory is not a ruin, but a huge machinery of destruction (cremation ovens included) left practically intact and presented like an empty stage. The aseptic presentation of this theater is complemented by the no less aseptic presentation of photographs and belongings of the slain – all arranged in the manner of minimalist series – and by the sober arrangement of the inscriptions (including the sinister ‘Arbeit macht Frei’ crowning the gate into the camp). The terseness, far from leaving visitors cold, impressed upon them a disturbing and sometimes distressing sublimity; a feeling borne out of their incapacity to fathom what they are perceiving – absolute evil – and reinforced by the fact that, however necessary it may be, the very act of recalling barbarity is in itself an act of barbarity.

Monuments like those at the Ardeatine Caves, Hiroshima, and Auschwitz work as theaters of memory based on the faithful preservation of scenes of tragedy and with the aim of creating cathartic atmospheres.

Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp, Poland (1940)

Minimalisms of Horror

The efficiency of these theaters of memory, compared to other monuments that evoke tragedies through abstractions, is evident in the memorial most talked about in recent years, as much because of the way it looks as on account of the controversies it has generated: the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, built in Berlin by Peter Eisenman. It’s radical thanks to the author’s wish to “not symbolize anything,” to let geometry alone take care of producing in visitors the catharsis expected of monuments of this kind. Over a hidden crypt, 2,711 concrete stelas measuring 2.38 x 0.95 meters rise from the ground in a deformed grid, varying in height between 0.2 and 4.8 meters to form a laconic warp. The grid seems to evoke the uncertain nature of Jewish identity, and the warps, the linguistic games Eisenman is so inclined towards, but beyond pedantic exegesis, the monument does end up relying on a not very sophisticated symbolism – the image of stelas emerging from the underworld as an oppressive labyrinth – and ultimately becomes a landscape which, however much the author’s intentions to create an atmosphere of strangeness, is familiar, recalling Richard Serra’s sculptural ensembles or Carl Andre’s minimalist series. Nevertheless, the cold intellectuality and sober materiality of the memorial is compensated for by the empathic experience of the visitor, who is oppressed by the concrete prisms and disoriented from wandering amid the stelas in the maze.

That it is no easy job to express remembrance of horror exclusively with the powers of geometry, shunning symbolism and any chilling presence of ruins, is well demonstrated in Eisenman’s memorial, time and again tainted by polemics that in one way or another have called into question its effectiveness as a monument. The most recent one was sparked by collages of the Israeli artist Shahak Shapira, where snapshots of tourists carefreely posing at the monument are juxtaposed with raw, shocking pictures of corpses in extermination camps. Artworks of this kind may seem sensationalist, but the questions they raise are not trivial: up to what point can geometry and minimalism provide what is expected of a monument to the dead?

Peter Eisenman, Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Berlin (2005)

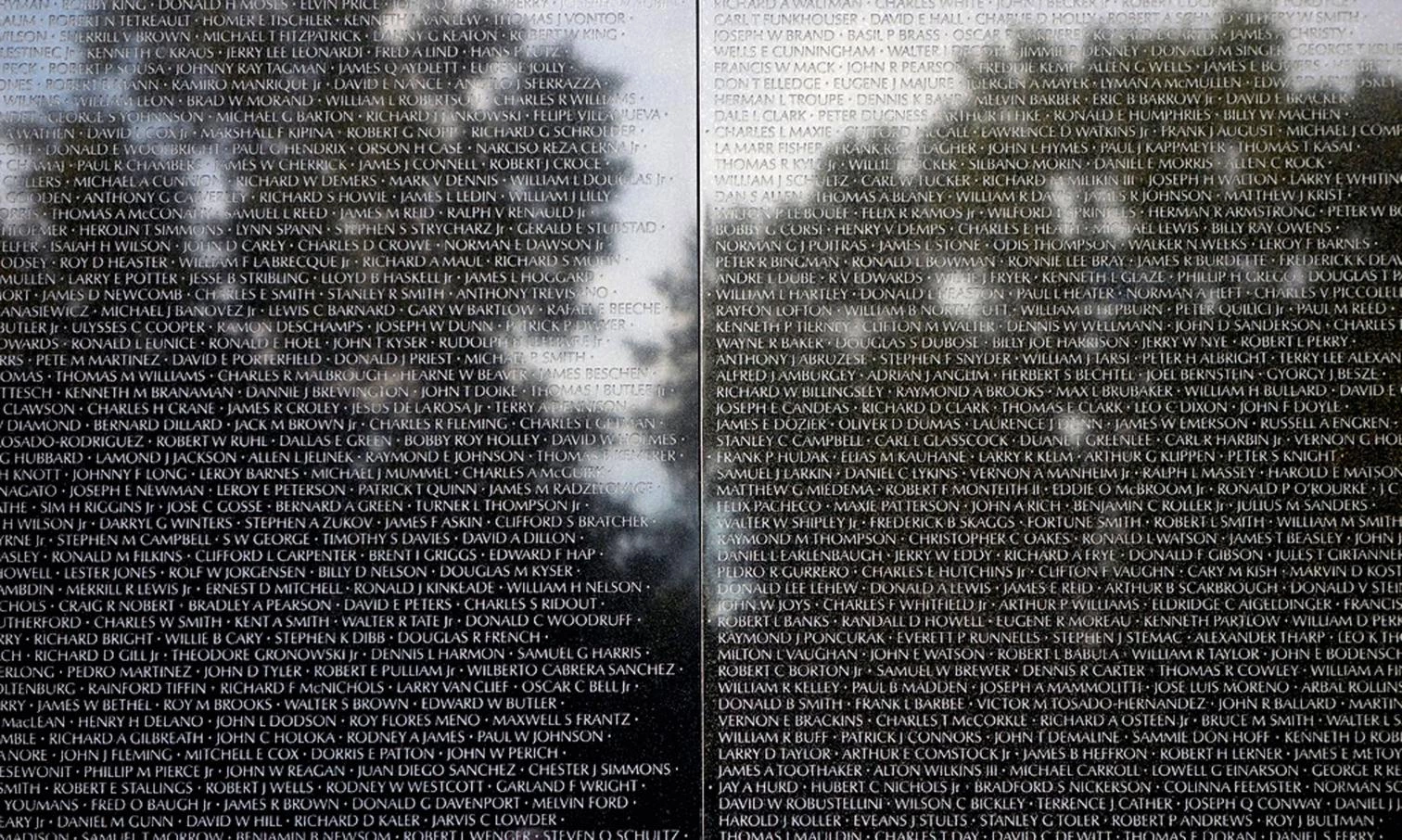

The question is also relevant to two other ‘minimalist’ examples, these in the United States, cradle of contemporary memorials. Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. is an elegant work whose effect lies in the careful selection and extreme simplification of symbolic motifs. The main one is the crack in the ground, picked out from the picturesque repertoire of Land Art but turned into a broken and sloping itinerary that gently cuts through the green field, scraping the flesh off a wedge-shaped side that features a second, no less powerful motif: a wall of black granite, main feature of what’s called the Commemorative Walk, on which are engraved, in a classic font, the names of the 58,307 killed in combat or missing, in the manner of a huge gravestone. The symbolic (the idea of the funerary stela), the picturesque (the contrast between green field and black wall), and the sublime (the immense inscription) combine in an at once silent and screaming monument, based on the less-is-more tone that the architects of modernity wanted, but not at the expense of character.

Maya Lin, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington D.C. (1982)

No less minimalist and refined but equally powerful is Michael Arad’s 9/11 Memorial in New York, a theater of memory that preserves the scene of the tragedy. But, more than actual remains of the World Trade Center Twin Towers (fragments of which are displayed in the annexed museum), what the monument harbors is the void they left, the objet trouvé formed by the two enormous squares in the ground, like a work of Michael Heizer transferred to an urban enclave or a scaled-up installation by Donald Judd. What’s interesting is that these minimalist references, in principle rather frivolous, are ultimately defused by the sublime power of two unfailingly romantic motifs: the forest on the public square, and especially the cascade which, falling on all four sides of each of the two squares, ends up swallowed by a huge geological drain leading, it seems, to Avernus. This effect combines with the interminable plaque bearing the names of those who perished, a dark perimetral parapet meant for both the eye and the touch, from which to take in the devastating presence of the monument.

The building of symbols is always a difficult task, and at a moment in time when there is nothing to celebrate, finding ourselves doomed to preserve the memory of genocides, nuclear destructions, and terrorist attacks seems like a morbid legacy. The ancients said that history is the master of life; Walter Benjamin, that there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. The question is whether to pay homage to memory by aestheticizing tragedy, or whether preserving the aura of horror would do us more good.

9/11 Memorial, New York (2011)