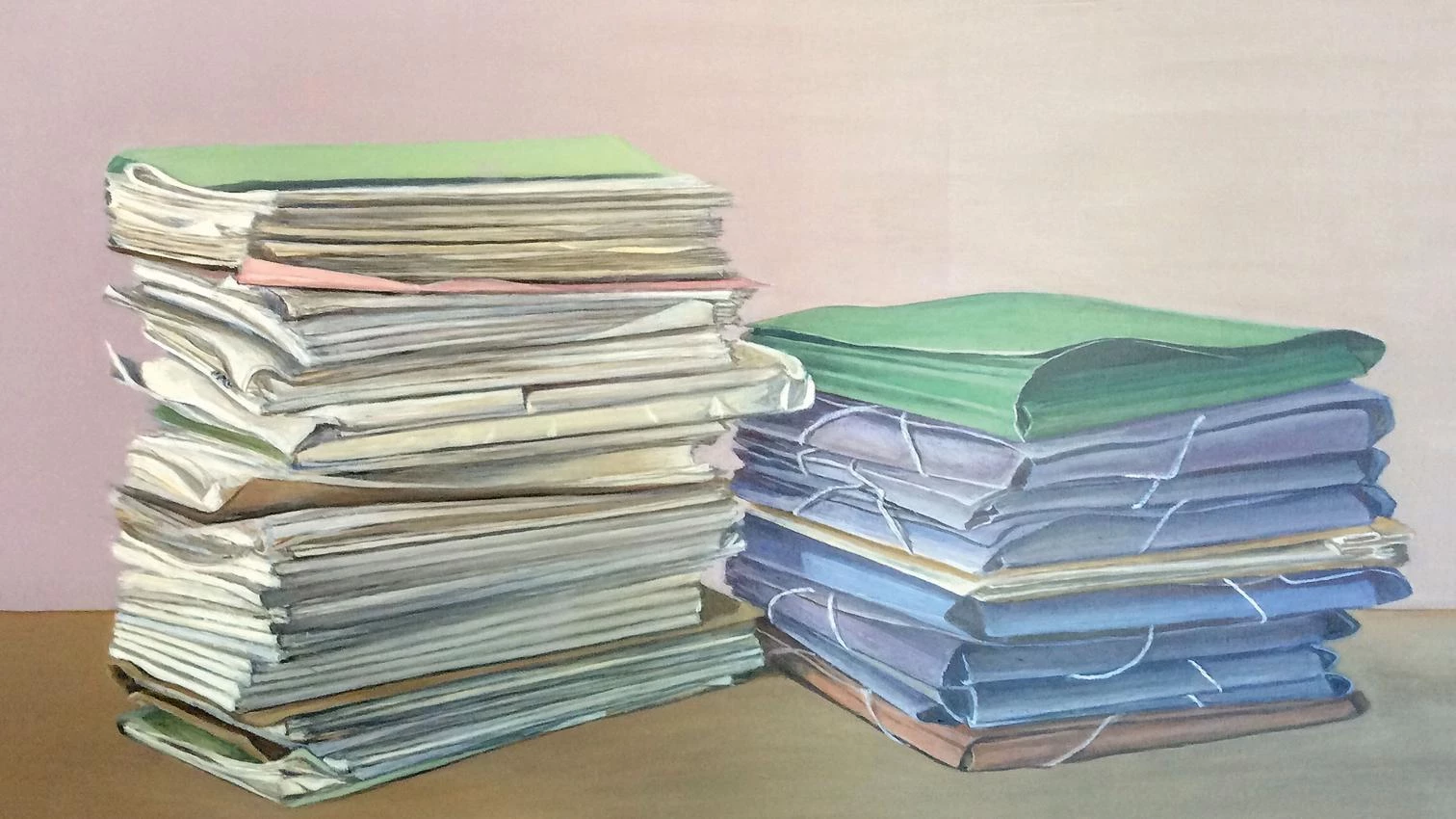

Late in the 1960s we submitted a design for stamping at the Murcia Institute of Architects, which was beginning to worry about the liabilities that could befall it if any project it approved was found not to comply with building codes then in force, and thus requested the inclusion in the project text of a line stating that “this project meets all regulations in force.” Since we were at it, I added: “and all those which might be in force in the future.”

We are not so far from my prophecy now that our project descriptions include several pages of obligatory clauses, reading (let alone comprehension) of which can take a few months.

Fortunately, not all the clauses involve prior administrative verification procedures. Those that do condemn one to months of discussions and corrections which, in general, have more to do with bad writing and wrong interpretation by the functionary on duty, than with meticulous work.

Then there is the interminable formality of codes affecting building services where what matters is not how things ought to be for them to function, but what is written on paper, sometimes since years ago and which no one has bothered to update.

A phenomenon as widespread as the proliferation of regulations logically has a reason behind it, none other than the general aversion to risks.

In the past, citizens were capable of making their own decisions, consciously or unconsciously assessing the risks they were taking, and in matters beyond their reach, such as health, they would put their trust in a professional of the field in question, who in turn took the risk of making mistakes, a risk that came with the territory.

The responsible citizen has given way to the ‘consumer,’ who has no responsibility over anything, and administrations watch over the welfare and safety of consumers by dictating rules without assuming the consequences in terms of time and money.

On the other hand, those responsible minimize consequences through insurance firms, which need objective criteria by which to delimit them.

Then one has to write the codes, and this is where the ‘experts’ come in.

I don’t know how things work in other fields (although I know that in medicine, the ‘clinical eye’ has been replaced by ‘protocols’ that include interminable analyses), but I have witnessed firsthand the formulation of the Technical Building Code.

My timid suggestion of the need for an objective analysis of real, existing problems (it’s enough of a tall order to avoid problems that arise, why complicate life with problems that someone thinks might arise) fell on deaf ears.

The building process was cut into pieces, each assigned to an ‘expert.’ Hardly any of the experts had ever built (or they wouldn’t be experts), and they were alike in not having a view of the whole, in not knowing how to write, and in hating simplicity.

The result has at the least served the real end: to limit the voracity for codes of local governments intent on protecting their ‘consumers’ with subtly distinct regulations; the tide of useless paperwork is at least more uniform.