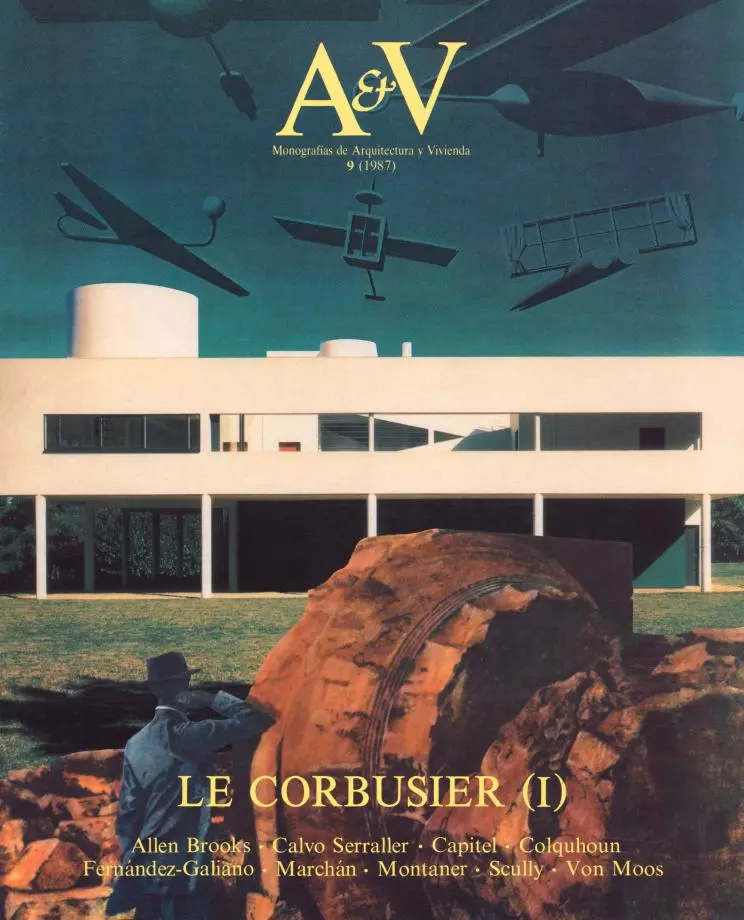

Le Corbusier, the architect who promised us machines á habiter, ended up building machines á emouvoir. The most influential and perhaps the greatest o f 20th-century architects was, above all, a boundless plastic artist, a polyphonic and protean creator of forms.

La clef, c’est: regarder... repeated the man who defined architecture as the wise, correct and magnificent play of volumes in the light. His vision opened his contemporaries eyes to the beauty of machines, ships and planes, but at the same time he was just as sensitive to the poetic eloquence of natural forms and the exact emotions of geometry.

The most modern of architects was also the last great classical architect. He transformed the language of his art with the precision and violence of Picasso or Joyce while proclaiming himself the heir of Michelangelo and Ictinus. He was trained in the sleepless experimentalism o f the vanguard but learned even more from the Acropolis and St. Sofia.

His grandness and his wretchedness are those of modern architecture. He constructed delicate and precise white villas, gigantic and muscular apartment blocks and lyric and rigorous religious buildings. He sought the protection o f a statesman so he could carry out his megalomanic and foreboding urban dreams. He thought he had found his Louis XIV in Petain and he ended up finding him in Nehru, for whom he built a monumental, beautiful, tragic and desolate city in India.

He was a polemicist and a visionary who wrote several dozen books to try to convert his contemporaries to the modern creed. His words have suffered more from age than his forms, but Vers une Architecture, published in 1923, will be remembered as the century most important manifesto. With one eye on the future and the other on history, he oversaw the eight-volume edition o f his complete works, a combined catalogue, authorized biography and apologetic self portrait that turned the discipline upside down.

Since the archives of the Le Corbusier Foundation were opened in the early 1970s, historians and critics have had more that a decade in which to broaden

that portrait and reinterpret the qualities that Le Corbusier attributed to himself and his work. Today the philosopher and the demiurge appear as an intense and insecure artist, a hypersensitive seeker in the dark depths o f irrationality, a penetrating gaze before the coded messages of form. His early purist work is admirable more for its syntax than for its logic, while one can hear archaic voices and surreal echoes in his late expressionism.

In may be that the new critical perspectives that place more importance on the poet than the reformer are merely reproducing the same path travelled by the architect in his long vital journey. The 78 years separating his birth in La Chaux-de-Fonds from his death in the Mediterránea represent, after all, an itinerary of knowledge that led Le Corbusier from fundamentalism to sensuality, from certainty to emotions, from ideas to forms, and from the snow to the sea.