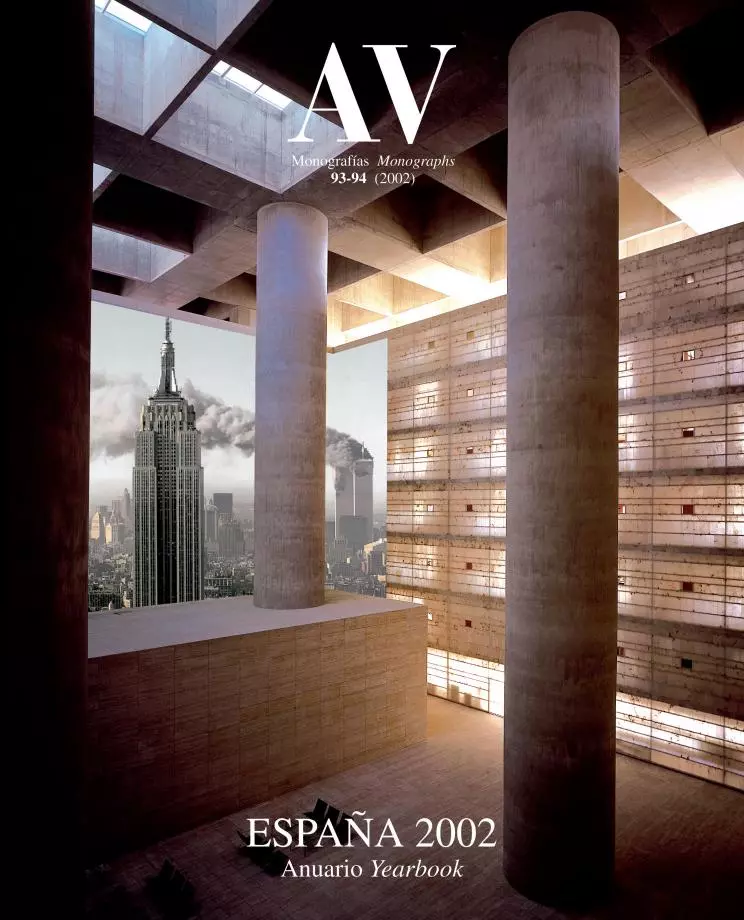

Searching Sert

The centenary of José Luis Sert (1901-1983) received less media attention than Spain’s most influential modern architect would have deserved.

Short of stature but tall in reach, José Luis Sert was great in Spain and even greater in the United States. But in the past three decades his reputation has suffered an unmerited erosion in both his native and adopted countries. In the militant seventies, Sert had the heroic stature of captain of the republican rationalist avant-garde, having built the mythical Spanish pavilion in Paris. In the revisionist eighties, he was the one Mediterranean architect who had moderated the radical excesses of modernity through a renewed attention to climate and landscape. And in the skeptical nineties, he was mainly seen as a prominent participant in the collective adventure of the CIAM, from its functionalist beginnings to its humanist and anthropological finale. This shift from bellicose feats to cosmopolitan conversations has dimmed the flame of his figure, blurring the essential coherence of a career that faithfully reproduces the course of architecture in the four central decades of the 20th century, and smudging the profile of a great personage.

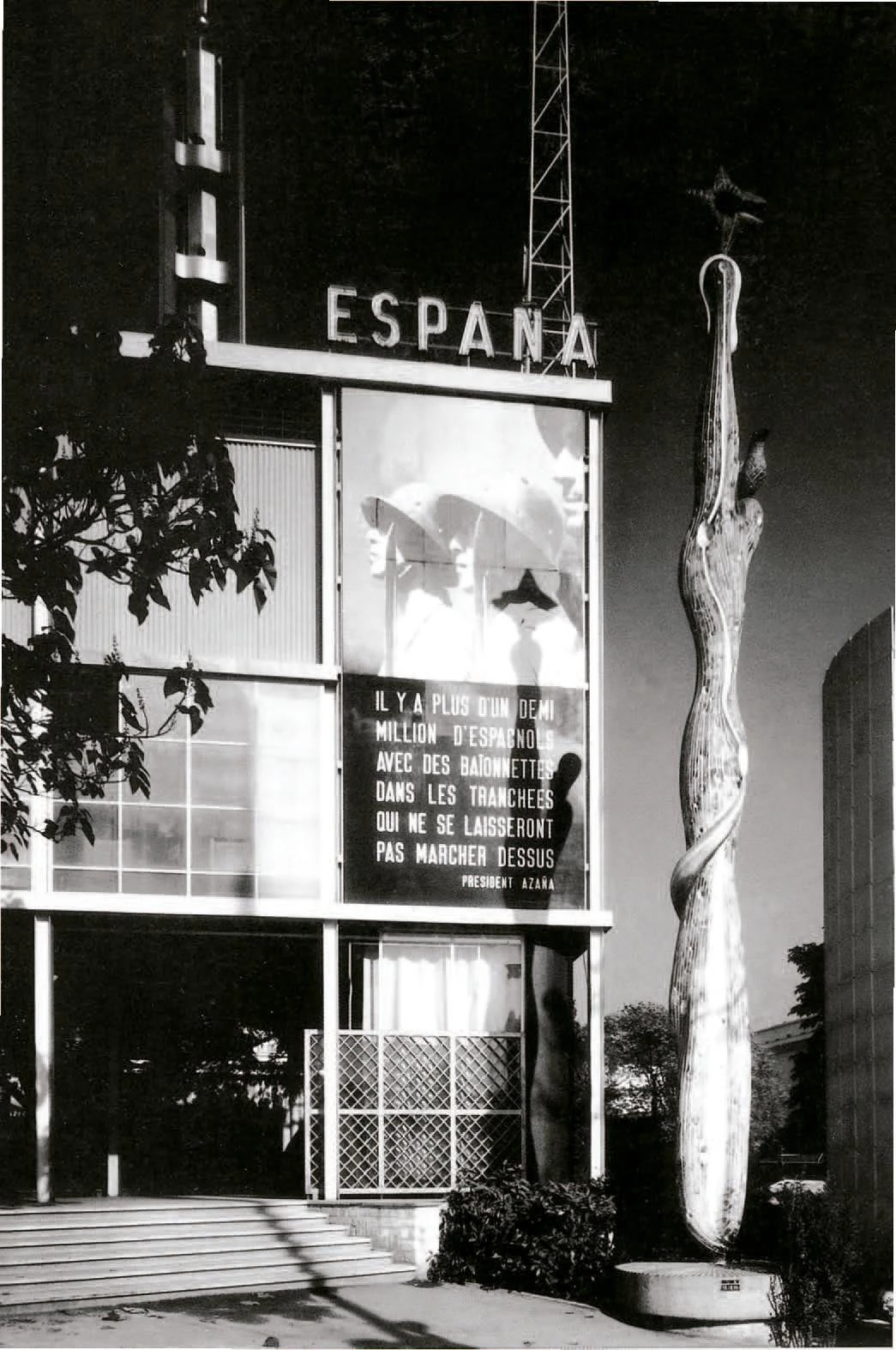

Spain participated in the 1937 International Exhibition of Paris with a pavilion by Sert and Luis Lacasa, where the display of works such as the Guernica of Picasso denounced the horror of a country at war.

Born in Barcelona in 1901 (1902 according to some manuals and his gravestone in Ibiza), the son of a textile industrialist who in 1903 would receive the title of count from Alfonso XIII, Sert was a sickly boy and an average student, but as a youngster he was sensitive to the convulsions of his time, and as such, he was infected with the virus of modernity long before earning his architectural degree. Fascinated with Le Corbusier, in whose Paris studio he worked in 1929, Sert was in the thirties the driving force of the Catalan rationalist group, a philocommunist aristocrat who got himself involved in major social projects of the republicans, from urban development schemes or the Plan Macià for Barcelona to architectural projects like the Casa Bloc housing for workers or the tuberculosis clinic, all in the course of a phase of political and cultural activism that would culminate in the dramatic Spanish pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair in 1937, a scream for succor of a republic at war that displayed, among other works, Picasso’s Guernica.

From Paris he went into exile in America, settling in the cosmopolitan milieus of the European avant-garde in NewYork, and setting up a city planning office that would carry out numerous projects in Latin America, from Brazil and Perú to Colombia or Venezuela, where functionalist Corbusian principles were mixed with symbolic and civic pre-occupations. These concerns took on theoretical form in books and manifestos like Can Our Cities Survive?, Nine Points on Monumentality, or The Heart of the City, authorship of which is often shared with his colleagues in the CIAM. The organization elected him president in 1947, making Sert a reference in the international architectural debate, and his house in Long Island a meeting point for many of the artistic and intellectual leaders of the time – a reflective and urbanistic period that would stretch on until his appointment in 1953 as dean of Harvard’s GSD, following Walter Gropius, and his definitive move to Boston four years later.

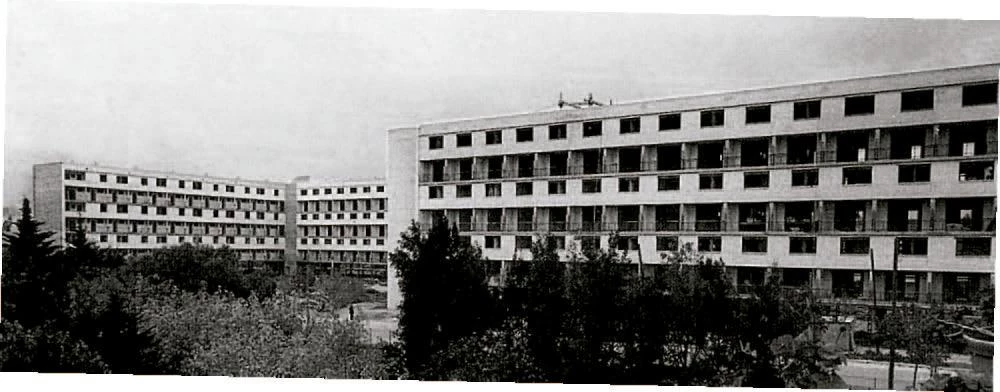

In his natal Barcelona, buildings of the first half of the thirties such as the one on Montaner street (below) or the Casa Bloc (left) show the strong commitment of the Catalan architect with the rationalist cause.

Sert stayed in the Graduate School of Design up to 1969, but those fifteen years of intense dedication to teaching also brought for him a reencounter, on one hand, with the landscapes of his Mediterranean youth, and on the other, with the building site, carrying out works on both sides of the Atlantic and on more agreeable, less schematic lines than in his early Catalan projects. In Europe, Joan Miró’s studio in Palma de Mallorca marked a path of return to the anonymous and vernacular certainties that had previously inspired the modern avant-garde, and under this would fall the Maeght Foundation in the Côte d’Azur, the Miró Foundation in Barcelona, Sert’s own house in Ibiza, and that product of admirable wisdom and spontaneity that is the Ibiza development of Cap Martinet, where he also had a vacation house. In the United States, his humanistic vision of modernity was expressed above all through the timeless intelligence of his own house-courtyard in Cambridge, a work which would be followed by the Holyoke Center at Harvard, the University of Boston campus, and, back in Harvard, the Peabody Terrace student residence and the Science Center, the latter a series of constructions on the banks of the Charles River that testifies to the architect’s formal talent and capacity to domesticate the exigent Corbusian principles.

When Sert ended his deanship at Harvard, Gropius celebrated his achievements in a letter which Josep M. Rovira’s monumental monograph on the Catalan architect reproduces as a prologue. In this letter, Sert’s friend and predecessor lauds his role in the organization of the CIAM, his leadership in the collaboration between the arts, his avant-garde convictions, his capacity to reconcile the Mediterranean spirit with the new world, and, above all, his humanist sensibility. This perceptive laudatio encapsulates Sert’s legacy, and perhaps also the reasons for his gradual fading away, which are the very same that have paled the prestige of the programmatic modernity of the pioneers, and pushed Gropius himself to a secondary plane, a merely ancillary one for pedagogic reference. With the heroic Sert of Barcelona absorbed by the activist recuperations of the seventies, the Mediter-ranean Sert of Ibiza and Boston depreciated by the introverted revisions of the eighties, and the theo-retical Sert of New York consumed by the existen-tialist aggiornamentos of the nineties, what is left is a figure succinct and fibrous, but still nutritious for contemporary architecture..

Sert left New York (below, his house in Long Island) for Boston when he replaced Gropius as the Dean of Architecture at Harvard, where he built in the sixties the Holyoke Center and the Peabody Terrace residence (above).

Take away the young aristocrat whom Oriol Bohigas describes as having ridden to Barcelona workers’ meetings in his mother’s Rolls Royce, its door decked with the count’s coat of arms. Take away the mature man in exile whom Xavier Costa has in an exhibit shown bullfighting Frederick Kiesler before Hans Richter’s surrealist camera, in the 11 x 23 meter living room of the Long Island house that felt like a civic center to his friends. And take away the veteran professor whom Maria LlüisaBorràs has presented as a Harvard resident dreaming of Ibiza’s still landscapes.What is left, as a solid residue of such sublimation of Sert’s biography, is an architect whose career is as consistent as his register is reduced, nutritious like powdered milk and thus better for remedying secular hungers than for satisfying capricious appetites of affluent and sated countries. In contrast to the succulent opulence of the Mies pavilion, which takes pleasure in its essential nakedness, the Barcelona replica of the Paris pavilion presents a lifeless skeleton that one might say is embarrassed not to be able to cover itself with the loquacious apparel of signs and art, sad like scaffolding without workers, and perhaps in tune with the abbreviated integrity of an architect who was dazzled by Le Corbusier but ended up follo-ing the numbered footsteps of Gropius.