Philip’s dead.” Peter Eisenman need not say the surname. We both know whom he is talking about. For half a century Philip Johnson has been so big in the New York architectural scene that everyone simply calls him Philip. I am surprised when Peter calls again. Just an hour ago we have been talking about the Harvard president’s sexist statements on women and science, the results of the Real Madrid of Vanderlei Luxemburgo and Manuel Fraga’s electoral chances in Galicia. Now he is sad and taciturn. Johnson was his godfather among Manhattan’s moneyed and cultured elites, and also the only person in the world who intimidated him. The times I saw them together, I could not help noticing their unique father-son relationship. Years ago it was I who relayed him the news of Aldo Rossi’s unexpected death. Now it is Peter who informs me before the obituaries appear on the web. It is almost eight in the evening, so I call the newspaper and commit to sending thirty lines in half an hour. That way the piece can make it tomorrow with a text by the daily’s correspondent in New York. As I write, I cannot push away the memory of Philip’s eyes, sparkling behind the round Le Corbusier spectacles that he, ever a Mies van der Rohe devotee, adopted as a paradoxical sign of identity

Above, the architect photographed by Arnold Newman in July of 1949, amid the reflections of his mythical Glass House.

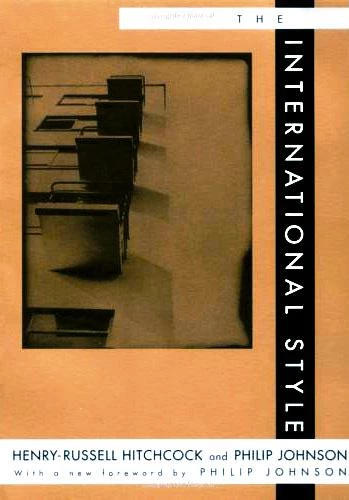

His 45 years of personal partnership with the gallery owner David Whitney may make one think otherwise, but Philip Johnson was a master of infidelity. Fortunately unfaithful in his political convictions, because after working in Louisiana for the fascist Huey Long, attending Nazi Party rallies in Nuremberg, and leaving New York’s Museum of Modern Art to devote himself exclusively to extremist militancy from 1936 to 1940 – when, fortunately, politics abandoned him –, after World War II he designed a synagogue and obtained the forgiveness of the Jewish financial magnates whose donations nourished the New York cultural institutions his career would unfold in. Alternatively unfaithful in his professional situation, which fluctuated between the practice of architecture, corporate patronage, and the exercise of criticism, so that in him the roles of author, patron, and arbiter of trends were confused. And inevitably unfaithful in his stylistic adherences, which passed from modernity to deconstruction through abstract classicism and historicist postmodernity: in 1932, with an exhibition in the New York MoMA, he introduced in the United States what he and Henry-Russell Hitchcock named ‘International Style’; in 1988, or 56 years later, with another MoMA exhibition he consecrated the fractured architecture of deconstruction.

I met him the year after that, while in Los Angeles as a visiting scholar at the Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities. We were introduced by Frank Gehry, whom I saw often at the time and who had just finished the Schnabel House, a huge residence in Brentwood built like a still life of pieces of different shapes and materials. Philip Johnson happened to be in town and wanting to visit the house, so Gehry made arrangements with the Schnabel family for us to go together, and so it was that I had the opportunity to spend a few hours in the company of the mythical octogenarian architect. He showed up with David, and in the course of the thorough tour of the house I was struck by the contrast between his physical fragility and his intellectual sharpness. He had to be held by the elbow to negotiate the steps and obstacles of the incident-filled yard and interiors, and the vulnerable skeleton of his frail figure was most at odds with the teasing sparkle of his gaze, the quickness of his replies, and the ease with which he would shift Marna Schnabel’s conversation toward her teenage daughter, butt of his jokes and attention.

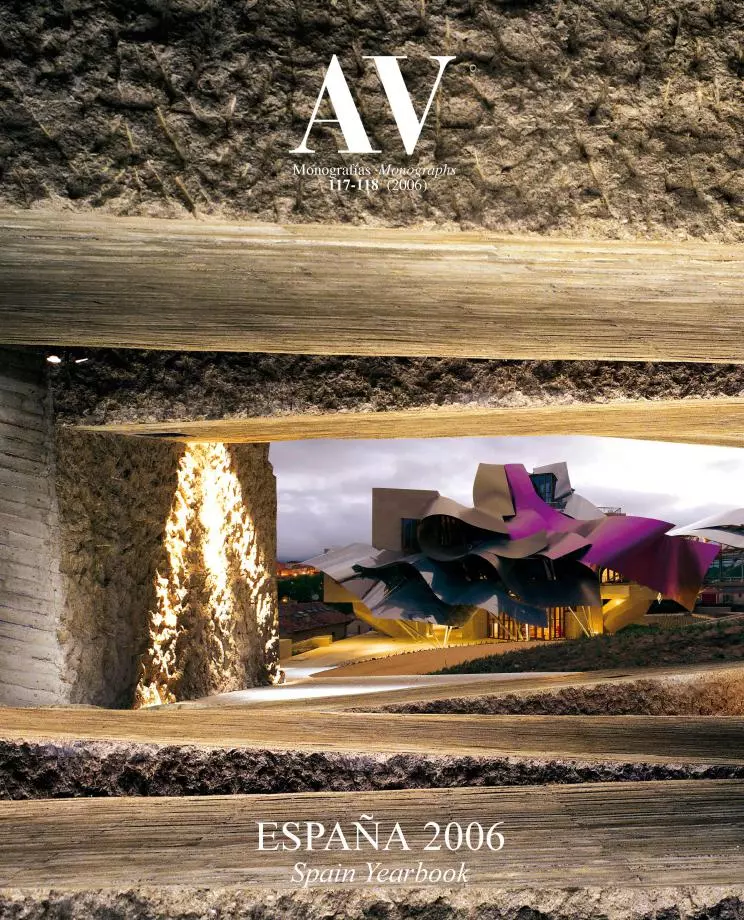

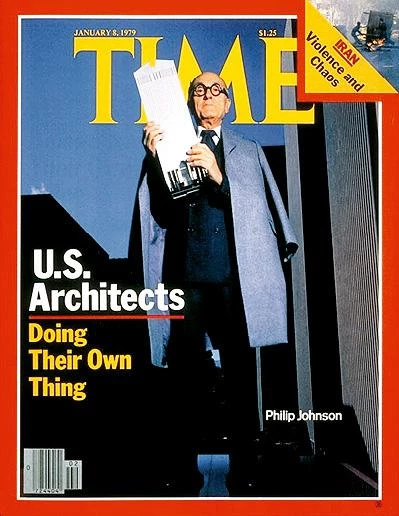

From the International Style to deconstruction, the intellectual and artistic interests of Johnson drew him towards a variety of experiences, appearing on magazine covers to defend the postmodern style or a project for a gay church.

On that occasion I was able to interrogate him on his current preferences and, inevitably, his relationship with Mies and his experiences in 1930s Germany, which he ironically skipped praising the quality of Nazi architecture. But the more extensive conversations would take place five years later, when I visited him in New Canaan in the company of Eisenman and family, and later in his New York apartment. That Sunday excursion to the Connecticut estate where Johnson spent his weekends, and where he now has chosen to die, gave me the rare privilege of seeing the nine constructions, scattered around in the beautiful, wooded landscape, through which the architect wished to sum up his ever-shifting aesthetic biography, from the early Glass House of 1949 to the then recently completed Gatehouse. Here he sequestered me for nearly an hour, asking me more questions than I could him. Some of the pieces were garden structures, such as the pond’s ‘ballet-classicism’ style temple – his most reviled period, in both his own and his partner’s opinion – or the metal fabric nursery cage he conceived as a tribute to Gehry; two were storage-galleries for his extraordinary collection of paintings and sculptures; and only two were used on an everyday basis: the opaque guesthouse he and David stayed in, the Glass House being climatically impossible to inhabit, just like Mies’s Farnsworth; and the postmodern library, with its large contemporary and historical collection, that Johnson used as a studio.

Notwithstanding the idyllic surroundings, I will never forget being struck by the austerity in which he lived. This is something I have seen in other American millionaire-patrons, such as Dominique de Menil, for whom Johnson built a modest house in Houston that speaks more of a teacher than an oil tycoon and who would introduce the architect in Texas, the state where some of his finest works are located, or Phyllis Lambert, through the intercession of whom Mies and Johnson obtained the commission for the Seagram Building – in whose Four Seasons Restaurant the architect for decades played the role of master of ceremonies of the American scene – and who lives in Montreal with a laconism that belies the architectural center she finances. (Years ago I took her out to dinner in Madrid with Peter Eisenman, and on the way to the restaurant we stopped for a close look of the KIO Towers; whereas the New Yorker got a kick out of finding references to his Checkpoint Charlie work in the facades, Lambert refused to step out of the car, so angry was she at Johnson’s drifting from his Miesian origins.) Later I would see his Manhattan apartment, in the tower that César Pelli built for the MoMA, having snatched the commission from Johnson himself. Small and low-ceilinged, it made the high-backed, Venturi-designed chairs in the dining room seem oversized. There, as we made preparations for an AV Monographs issue to celebrate his 90th birthday (a project aborted because the break with John Burgee in 1992, after 25 years of professional partnership, had placed an embargo on all of the firm’s drawings), I dared to suggest that he put some kind of order in MoMA’s permanent architecture collection, then displayed with neither concord nor criteria. “I don’t dare tell them anything” – he had long let go of his responsibilities in the museum – “because they still take it as an order.” (In the wake of the museum’s reopening in Manhattan, the architecture section – named after Johnson, incidentally – remains defficient, in contrast to the splendid art collection exhibited on the floors dedicated to Alfred Barr.)

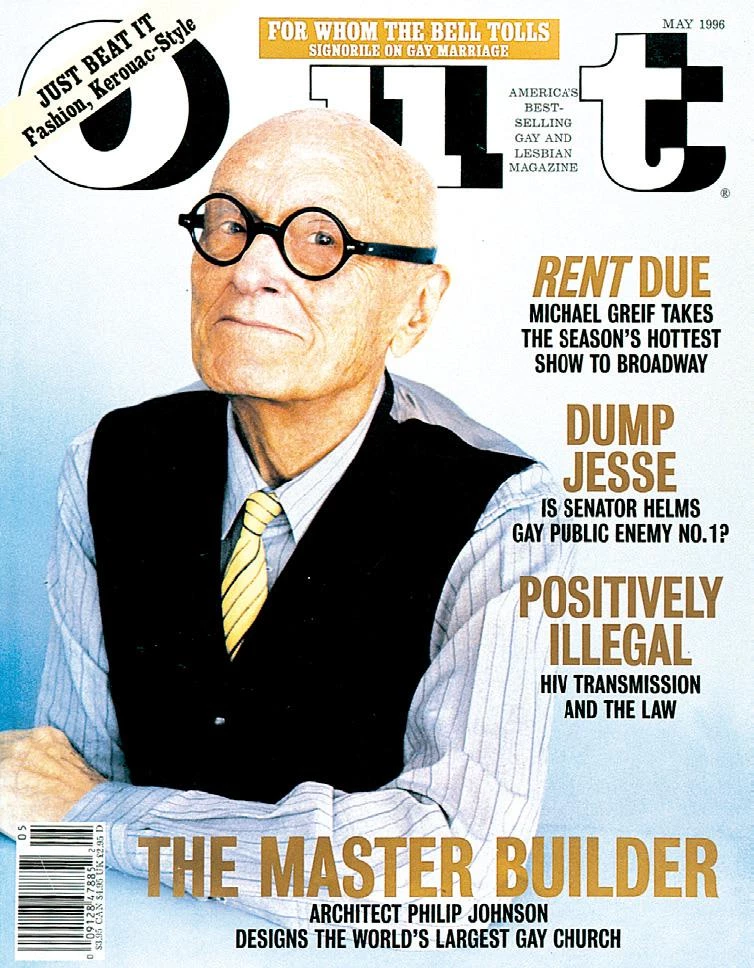

Too powerful at the MoMA, in New York’s high society, and in American architecture – he received the first Pritzker Prize, orchestrated the second for Barragán, and oversaw the award’s initial steps –, he aroused as many furious detractors as he attracted devotees. Michael Sorkin wrote ‘philippics’ in The Village Voice, coining an entire literary genre for censuring his fickleness, his inconsistency and his formalist triviality, while other young critics like Jeff Kipnis or Mark Wigley praised his versatility and adaptability, as well as his sensitivity to the spirit of the times. Having been educated in the lambasting of Johnson (my teacher, the late Alejandro de la Sota, would make in the classroom detailed comparisons of the Glass House and the Farnsworth House in order to show to what extent the disciple was unworthy of the master Mies), but also having visited most of his works, I must say that both sides are well-founded. In his determination to emulate Mies van der Rohe, Johnson hired Franz Schulze, author of the German master’s celebrated biography, to write up his own. Published in 1994, the resulting book – where both his episodes of fascist militancy and his complicated sentimental life take up a significant place – was a mirror he did not like looking at. Nevertheless he once again in mea culpa acknowledged the error of his totalitarian youth, attributing it in part to an erotic fascination with the Nazi aesthetic, and appeared on the cover of Out, the voice of homosexuals, to announce that he would design the world’s largest church for gays and lesbians. .

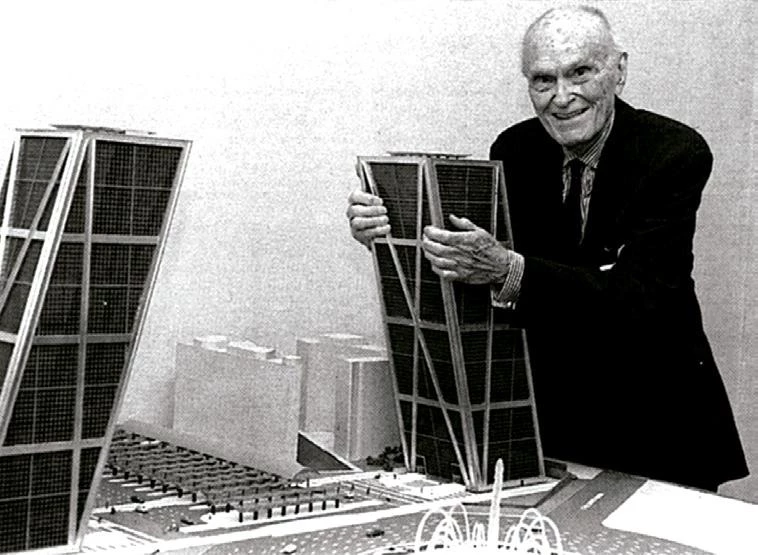

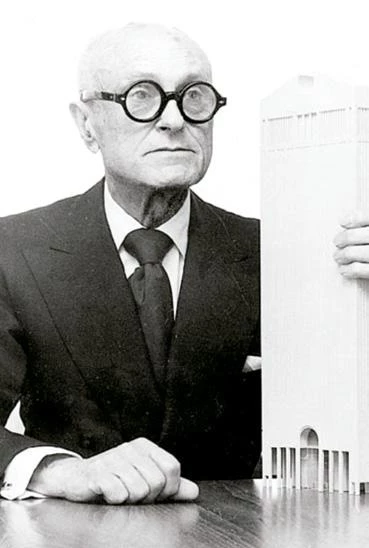

Above, Johnson in 1996 with the model of the KIO towers, and in 1978 with that of the AT&T tower

Because of the newspaper’s rush, I write a page threaded by his structures in New Canaan. I believe it is in this museum-park, donated to the National Trust, that his memory will live on in most perfect, innocent form. Historians will prefer the MoMA’s sculpture garden, from where one discerns the top of the AT&T skyscraper (the model of which he appeared with on the cover of Time magazine), like a visual oxymoron connecting the modern Johnson to the postmodern, the institutional to the corporate and the cultural to the mediatic. As I wrap up the piece, newsflashes begin to come on the web: a deplorable text of Associated Press and an article by Paul Goldberger that The New York Times must have had ready since the prehistoric times in which the critic wrote for it. Like the writer Javier Marías, I still cannot fathom how people can prepare obituaries ahead of time. Maybe it is more professional, but I find it obscene. At the newspaper they decide to illustrate the information with a 1978 picture of Johnson with the AT&T model, after not finding the one we published in May 1996 with the architect embracing the model of the KIO towers. Had it been up to me, I would have used the photograph Arnold Newman took of him in July 1949, with Johnson seen from behind in his Glass House, lost among the reflections of the trees like a character in an oneiric and improbable story, out of scale like his own life. Thanks for calling, Peter.