Louis Isadore Kahn was born on 20 February, 1901 in Osel (now Saaremaa), an island closing the Gulf of Riga in the Baltic Sea, then belonging to Russia and currently to Estonia but at other times to Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Germany. His parents – the Estonian Leopold Kahn, paymaster of the Russian Imperial Army and clerk after leaving it, and the Lithuanian Bertha Mendelsohn, who played the harp and loved literature – were Jews of large families whom a modest education could not save from extreme poverty, inducing them to emigrate to the United States a few years after they were married. The family settled in Philadelphia when Louis was five, and there they lived in difficult conditions. Never able to pay rent, they moved as many as seventeen times in a matter of two years, maintained by the woollen clothing that the mother weaved for factories – since her husband could not land a stable job in the occupation he had chosen, painting stained glass windows –and sustained, emotionally, by the Yiddish and the music that Bertha kept alive to conserve their European cultural roots.

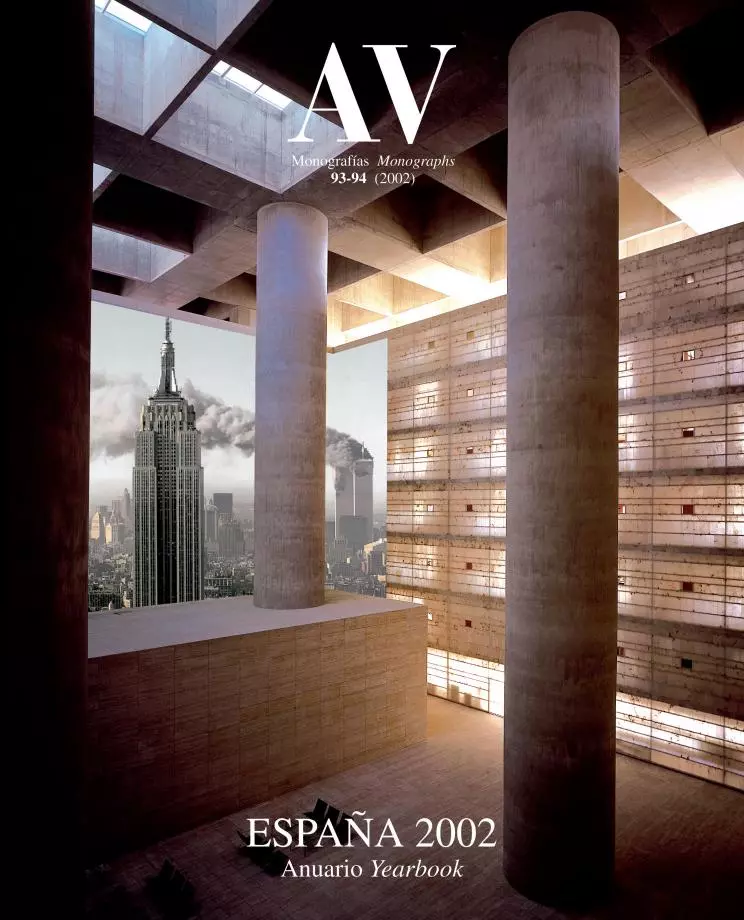

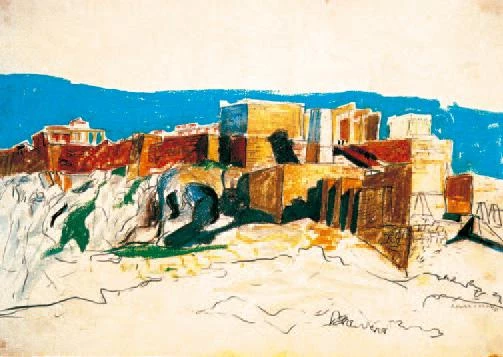

The classicism of Kahn acquires an almost cosmic resonance in the monumental Capitol center of Dacca, and it is refined to perfection in the delicate false vaults of the Kimbell Art Museum at Fort Worth.

Such an atmosphere of misery and determination that surrounded the childhood of Louis and his two younger siblings was aggravated, in his case, by the face and hand scars caused by the embers of a fire he had fallen into at the age of three and almost killed him, and by the high-pitched voice that was the after-effect of a bout of scarlet fever shortly after arriving in the America – physical defects that aroused both abusive treatment from hisclass-mates and the protection of his mother, convinced as she was of his artistic talent and tenaciously resolved to tap it. Good at drawing like his father, young Louis obtained the early recognition of his teachers, who directed his career toward painting. But he was also endowed with his mother’s musical ear, and a practically self-taught skill on the piano earned him a scholarship at the conservatory which he finally rejected, choosing to develop his artistic capacity in architecture while using his musical gifts – by playing the organ to accompany silent films – to finance his studies.

As a student in the University of Pennsylvania, he was fortunate to be in a class under Paul Cret, a distinguished French architect who brought to Philadephia the rigor of the methods of the École des Beaux-Arts of Paris, and in whose office Kahn would work for a while in 1929, after a year-long trip to Europe in which he invested the savings from his first professional employments. The Depression interrupted all ongoing construction, however, and all Kahn got to do in the thirties was collaborate in some of the housing projects undertaken by the administration in the context of the New Deal. He spent much of that decade reflecting and participating in the debate about the future of architecture, maintained by the family of Esther Israeli, a research assistant at the University of Pennsylvania’s Neuro-surgery Department whom he had married in 1930. This period of professional stagnation ended when the United States joined the Second World War and Kahn redirected his career toward social activism and urbanistic projects drawnup with George Howe until 1942 and Oscar Stonorov until 1947, the year he was elected president of the American Society of Planners and Architects (equivalent to the CIAM in Europe), set up his own practice, and began teaching at Yale University.

A stimulating environment of students and professors steeped in the transformation of academic education and the introduction of modern principles,Yale provided Kahn with a diving board in two forms: a young art historian, Vincent Scully, who was to become his most active propagandist; and a commission, the university’s ownArt Gallery, which he executed with a delicate brutality that was rare in the conformist panorama of American institutional architecture, with slabs of tetrahedral coffers and a triangular staircase inserted in a concrete cylinder destined to be widely imitated, and which would bring world fame to a heretofore marginal figure. The rest of the story is well-known, and is punctuated by a chain of works that gave a wholly new meaning to contemporary monumentality: buildings of an archaic solemnity, exquisitely constructed and rigorously choreographed through elementary geometry, at once imposing and intimate, and as lyrical in their molding of light as they are eloquent in their definition of the encounters between materials.

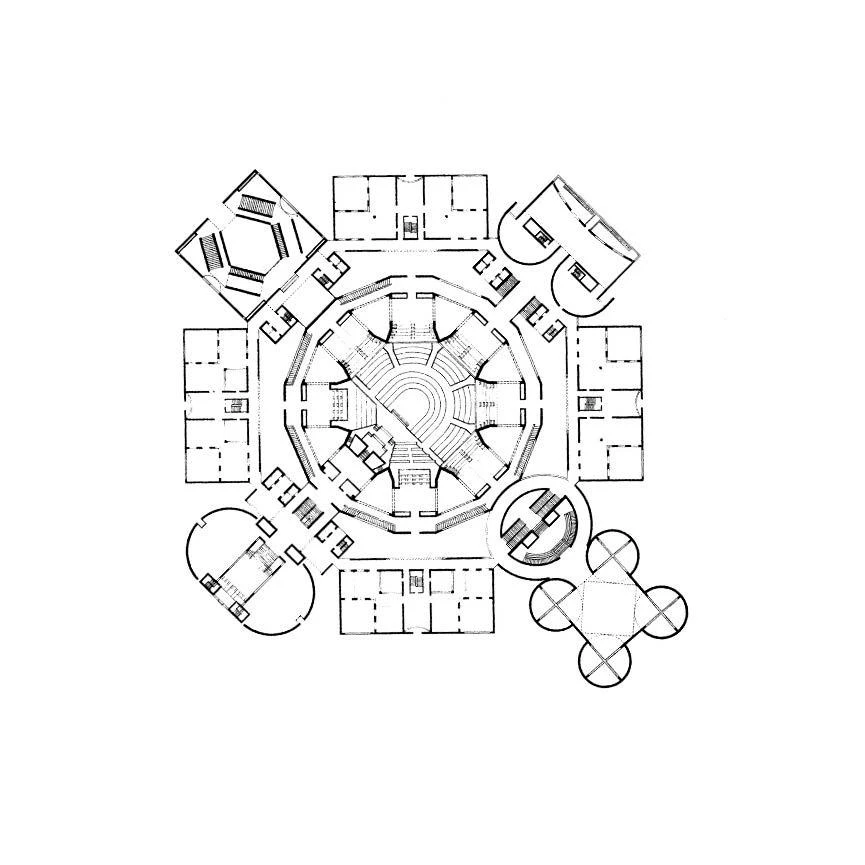

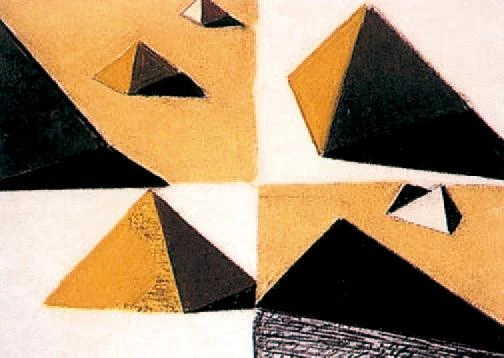

The symbolic power of the Capitol of Dacca (right) lies in its geometric rigor, and that severe formal discipline is the starting point for the dialog with landscape in the monastic premises of the Salk Institute (below).

The pyramidal roofs of the Bath House in Trenton, the project in which Kahn claimed to have “found himself”, the medievalist towers of his Richards Medical Laboratories in Philadelphia, where he first materialized his concept of servant and served spaces, and the huge open court opening on to the horizon at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, a science monastery that translates the architect’s obsession with Villa Adriana to a modern language, are three masterworks conceived in the second half of the fifties. The beginning of the sixties in Kahn’s career is dominated by his great Asian projects: the Indian Institute of Management at Ahmedabad and the formidable Capitol center of Dacca (in what later would become Bangladesh), a parliamentary citadel for a young Islamic country built like a fortress of concrete cubes and cylinders perforated by circles and triangles, where the romantic classicism of Piranesian flavor that nourished this phase of his life acquires cosmic resonances.

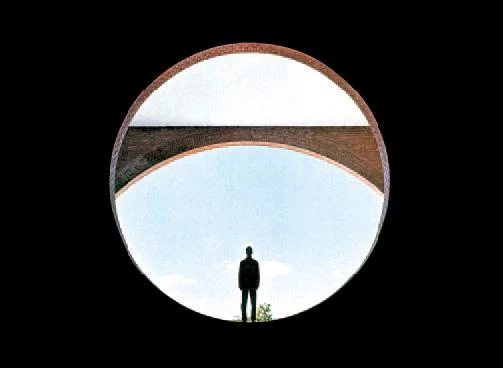

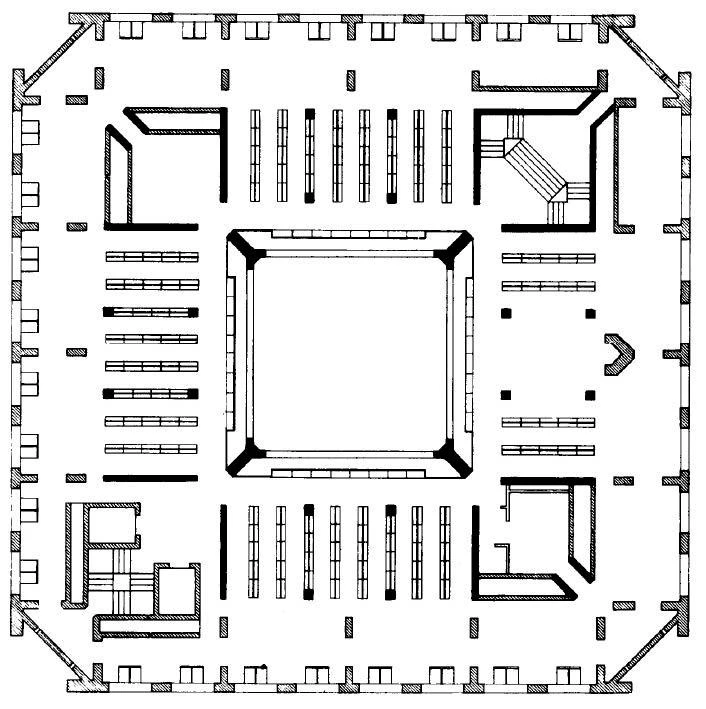

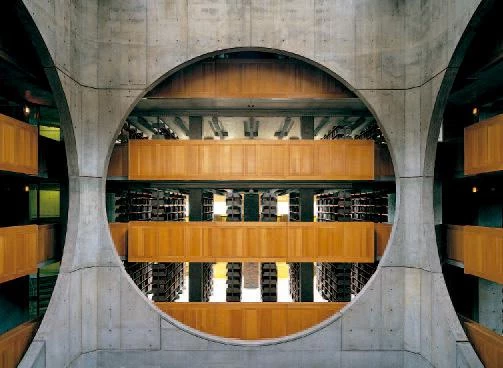

Kahn purified his language further in the later sixties, designing three works of dramatic perfection: the Library of Exeter, a brick cube whose absent corners evoke the Roman ruins he so loved, and where the luminous courtyard’s gigantic oculi of concrete recall the enlightened dreams of Ledoux; the Kimbell Art Museum at Fort Worth, a succes-sion of false vaults of concrete, split by longitudi-nal skylights, which create a timeless and elegant, exquisitely serene atmosphere; and the Yale Center for British Art, situated in front of the Art Gallery that had first earned him recognition twenty years before, an urban prism of concrete, glass and steel that arranges the rooms of the museum around two courtyards characterized by painstaking exactitude and geometric solemnity – which Kahn would never see completed.

By the beginning of the seventies his popularity had made him a constant traveler. In what was to be the last year of his life he flew once or more times to Dacca, Teheran, Tel Aviv, Brussels, Paris, Rabat and Katmandu. On the afternoon of Sunday 17 March, 1974, back from a long journey to India, where he had visited his building in Ahmedabad, and after an interminable return trip with stops at Bombay, Kuwait, Rome, Paris and London, an exhausted Kahn collapsed in the toilets of New York’s Pennsylvania Station, where he was to take the train that would take him back to Philadelphia, and his body with a broken heart remained for days in a re-frigerated box of Manhattan’s Department of Missing Persons. He had lived fifty years of obscurity and some twenty of brilliance, and was consumed in the bonfire of success – leaving, however, a mark of buildings that have become part of the heritage of architecture and of humanity.

The library of Exeter (right) or the Kimbell Art Museum (below) sum up the legacy of Kahn, who gave a monumental sense to modern abstraction and was a master in the use of light and in the material detailing of architecture.

1 SHOULD WE CELEBRATE KAHN’S ANNIVERSARY?

Not absolutely necessary. From 1991 to 1994, a colossal exhibit traveled to seven museums on three continents, and the catalog edited by the University of Pennsylvania professors David B. Brownlee and David G. De Long, which compiles the essential part of the research made since 1983 in the archives Kahn bequeathed to his alma mater, continues to be the basic reference for the study of this 20th-century giant. The publication in 1997 of The Rome Letters, which Louis Kahn wrote in 1953 and 1954 to his lover Anne Griswold Tyng, an architect twenty years his junior who went away to have their daughter far from Philadelphia, throws unexpected light on the obsessive and petty personality of the master. But the essential revision of Kahn was undertaken a decade ago, so the current commemoration is doomed to be more festive than inquisitive. If musicians, philosophers and writers are celebrating the years of Verdi, Gracián and ‘Clarín’, respectively, why should architects not mark the 100th birthday of Kahn? Although the truth is that, adding up birth and death centennials and all other singular events of biographies and oeuvres, not to mention fiftieth anniversaries or sesquicentennials, any cultural figure can be paid homage at any time. Last year only the Venezuelans honored, in their Venice pavilion, the centennial of Carlos Raúl Villanueva, a figure surely worthy of wider recognition, and we can only hope that the centenaries of José Luis Sert in July 2001 and Luis Barragán in March 2002 will have dimensions far exceeding the Catalan and Mexican scopes. In the meantime, let us raise our glasses in honor of Kahn, a Jew from Estonia and Philadelphia who now belongs to the world.

2 IS HE ONE OF THE CENTURY’S GREAT ARCHITECTS?

He is. If the United States is a great country, Louis Kahn was a great architect whose importance lies in an American interpretation of old themes of the Old World, a destitute immigrant welcomed by his adopted country with generous intelligence, and a perplexing talent who could only flourish in the pos-itive and optimistic framework of American patronage. There would be no Kahn without Jonas Salk, Kay and Velma Kimbell, or Paul Mellon. His revision of functionalism to build modern monuments which could express the desire of institutions for permanence and celebrate the cohesion of the community was as characteristic of the postwar pax americana as Wright’s houses were of the Emersonian individualism of a nation of farmers. But his formal discoveries are by now a patrimony of world architecture. Only a Eurocentric shortsightedness and the late launch of his career still deny him a place in the hall of fame, those Jencks calls the big four (Wright, Mies, Le Corbusier and Aalto) and whose complete work historians of Docomomo are lobbying for the Unesco to declare part of World Heritage, along with 28 buildings by minor figures including Kahn’s Richards Laboratories. Nevertheless the master of Philadelphia is, along with the now unjustly underestimated Gropius, the only one mentioned, besides the big four, in the chapter titles of the most widely diffused history of modern architecture, written by William Curtis, and rightly so in my opinion. Though he may lack the mythical stature of Wright, Mies or Le Corbusier, perhaps the Unesco would do well to change the big four to the big five, and hence no longer guarantee Kahn’s work less protection than Aalto’s.

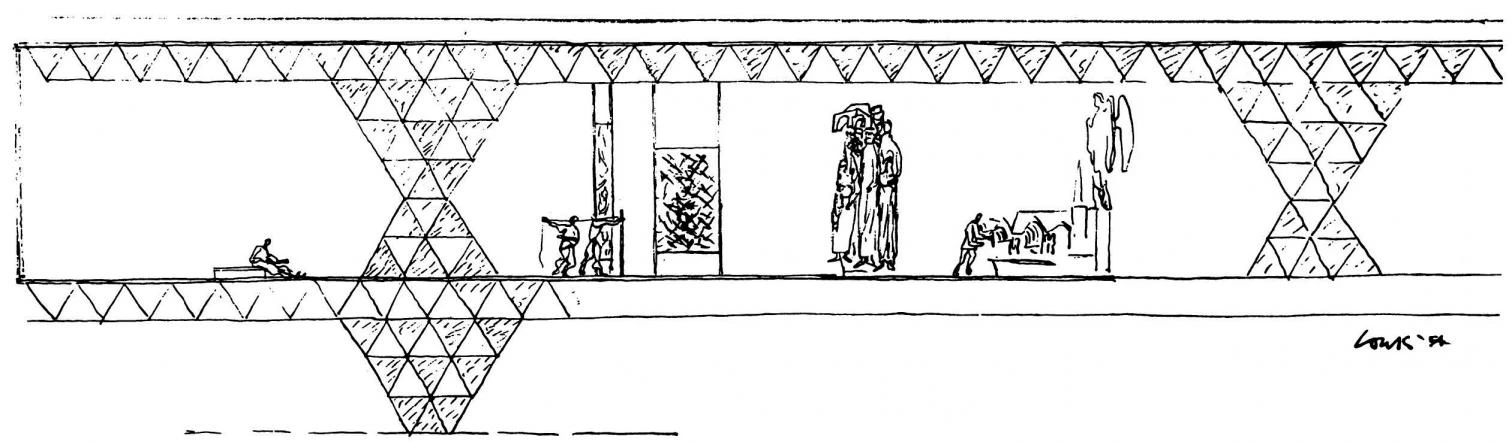

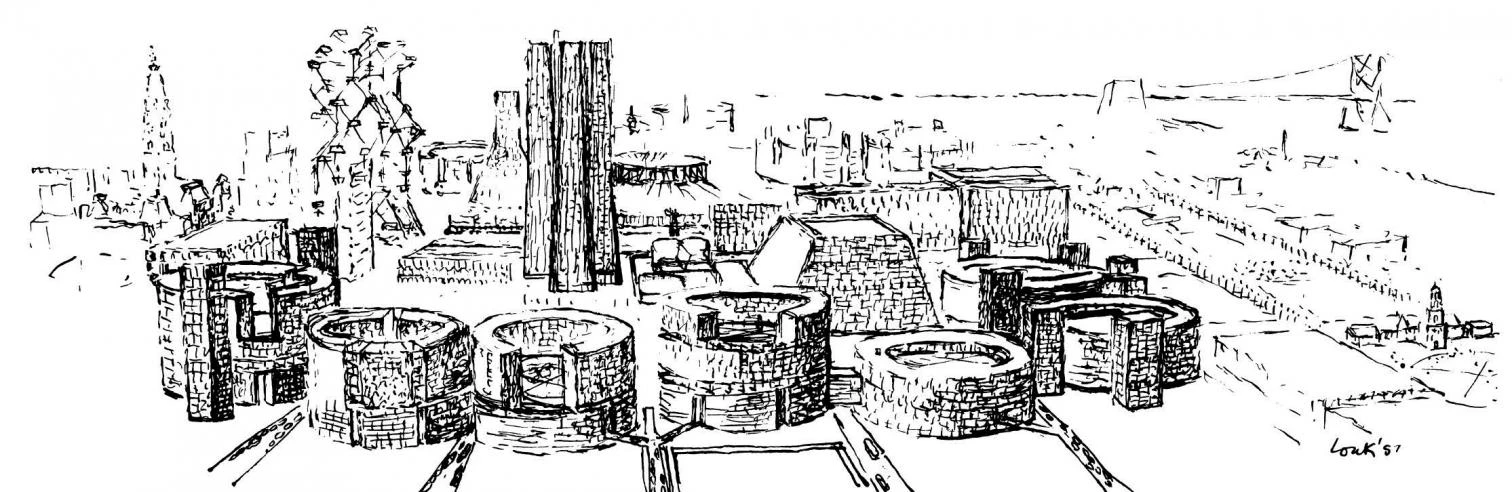

The structures of Fuller inspired the tetrahedral coffering of the floor slabs at the Yale University Art Gallery (left); and a repertoire of elementary geometry unfolds in the project for the center of Philadelphia (right).

3 ARE HIS DEBTS TO OTHERS ADEQUATELY RECOGNIZED?

Not at all. Kahn was never short of gratitude for the beaux arts teachings of his master Paul Cret, who in the twenties trained the architect in the rigor of geometry; for the essential support of his colleague George Howe, pioneer of the International Style and Kahn’s protector during the difficult years of the Depression and the war, who as dean at Yale procured for him his first major commission, the university’s Art Gallery; or for the enthusiasm bordering on dithyramb of the historian Vincent Scully, who found in the eccentric Kahn the heroic and archaic genius that fitted his dramatic vision of art history, and became the architect’s leading publicist in the fifties and sixties. Deplorable, however, is Kahn’s resistance to acknowledging his debt to his collaborator and lover Anne Tyng, who between 1945 and 1955 introduced the abstract order of structural geometry into his work, becoming a bridge with the fertile inventiveness of Buckminster Fuller; to his disciple and collaborator Robert Venturi, who worked in his studio in 1956 and familiarized Kahn with the poetry of the stratified and juxtaposed spaces of mannerist architecture; or to the engineers around him such as the French Robert Le Ricolais, collaborator from 1953 on and colleague from 1955 at the University of Pennsylvania, but especially August Komendant, Kahn’s regular adviser after 1956. Tyng was, as Fuller quite perceptively wrote, “Kahn’s strategist in geometry”; “Lou learned from Bob,” in the vindicative words of Venturi’s wife and partner Denise Scott Brown, “the exception, the distortion and the inflection characteristic of mannerism”; and the great works of the last two decades of the career of someone who “lacked the most basic knowledge of structures” would not have been possible without Komendant, the engineer who so undiplomatically described the architect’s technical ignorance.

4 WAS HE THE FATHER OF POSTMODERN STYLE?

Only superficially. It is true that figures of post-modernism such as Charles Moore trained under him; that works like Mario Botta’s are not conceivable without his influence; and that when he crossed paths with Venturi his career made a significant turn, incorporating the scenography of the false facade and the evocation of historic architectures. But the term postmodern has now acquired pejorative connotations that associate it only with a frivolous form of superficial classicism, and it would be absurd to find its origins in Kahn’s essential archaism, a self-referring fundamentalism that subordinates context and language to his geometric mandalas. Indeed he returned respectability to history; but the lessons Kahn extracted from Rome or the ancient world do not differ in substance from those Le Corbusier noted when he represented the Eternal City through the crystalline eternity of platonic solids, encountering in elementary geometry a classicism more profound than that of the amiable figuration of pediments, garlands and volutes. Venturi learned other lessons in Italy, and would learn even more from the casinos of Las Vegas, while Aldo Rossi dug into his personal and geographic memory to find a set of archetypes different from Kahn’s: lyrical and tragic instead of cos-mic and solemn, as befits the contrast between his individual explorations and the Philadelphia master’s obsession with the mythical origins of collec-tive spaces. On 18 January died in Miami the architect Morris Lapidus, a Slav like Kahn and of the same age (he was born in Odessa in 1902), who like him spent the fifties undermining the routinary neutrality of the International Style. But to establish through Venturi a link between Kahn’s severe institutions and Lapidus’ motley, ironic and excessive hotels would be a theatrical pirouette exceeding the threshold of permissible cynicism..

5 WHICH ARE MORE IMPORTANT, HIS IDEAS OR HIS WORKS?

His works, by far. Although Kahn was a charismatic teacher, the numerous texts through which he crystallized his ideas are a disjointed and confusing amalgam of aphoristic intuitions and trivialities glazed with historic errors, often as obscure as a shaman’s dictums and sometimes more hermetic than a sibyl’s prophecies. Kahn boasted that he never read, and the hemorrhagic torrent of metaphorical speech that fascinated his disciples disconcerted his clients, whom he at the outstart scared away with his slovenly, eccentric appearance. What rescues Louis Kahn are the works of the last two decades of his life. Up to the age of fifty he was a hard-working professional, building cheap housing for the federal government or Jewish associations while promoting modern architecture through various publications and organisms. But on his return from a three-month stint in Rome in 1951, he designed the Yale University Art Gallery, and with this and the Trenton Bath House of 1955 the architect embarked on a period of extraordinary fertility and creative originality that would only end with his death in 1974. The buildings of this final phase combine monumentality and delicacy with a rare sensibility that cannot fail to move: the huge metaphysical plaza facing the Pacific of the Salk Laboratories is flanked by secluded study cells where oakwood domesticates concrete; the parallel cycloid vaults of the Kimbell Museum give each piece of its exquisite painting collection an intimate atmosphere of luminous contemplation; and the enormous oculi of the inner courtyard in the Exeter library strike an unexpected contrast with the wooden cubicles, set in the precise brick facade, that embrace the readers in their minimal spaces. Anyone who has visited these magical sites must have felt that, beyond architecture and its stories, in such places happiness is at hand.

The structures of Fuller inspired the tetrahedral coffering of the floor slabs at the Yale University Art Gallery ; and a repertoire of elementary geometry unfolds in the project for the center of Philadelphia (right).