The Latest in Lumps

The British Future Systems and Peter Cook have built in Birmingham and Graz two biomorphic blobs that prove the enduring vitality of the futurism of the sixties.

Economic bubbles produce architectural bubbles. The accelerated white-hot prosperity of the sixties gave us the colorist collages of Archigram, complete with walking cities on telescopic legs, lysergic kaleidoscopes of yellow submarines, and circuses of pop banderoles; it also gave us the inflatable ephemeral constructions of the hippie festivals, and the geodesic structures that Buckminster Fuller turned into a symbol of the counterculture. The financial bubble of the nineties would bring the same paraphernalia to our computer screens, designed at times by the same old rockers but now stripped of all messages of social utopia, removed from technological experimentalism, and meekly placed, instead, at the service of commercial and cultural spectacle. Cases in point are two blue bubbles recently completed in Birmingham and Graz by veteran architects pretending to be materializing dreams of their youth.

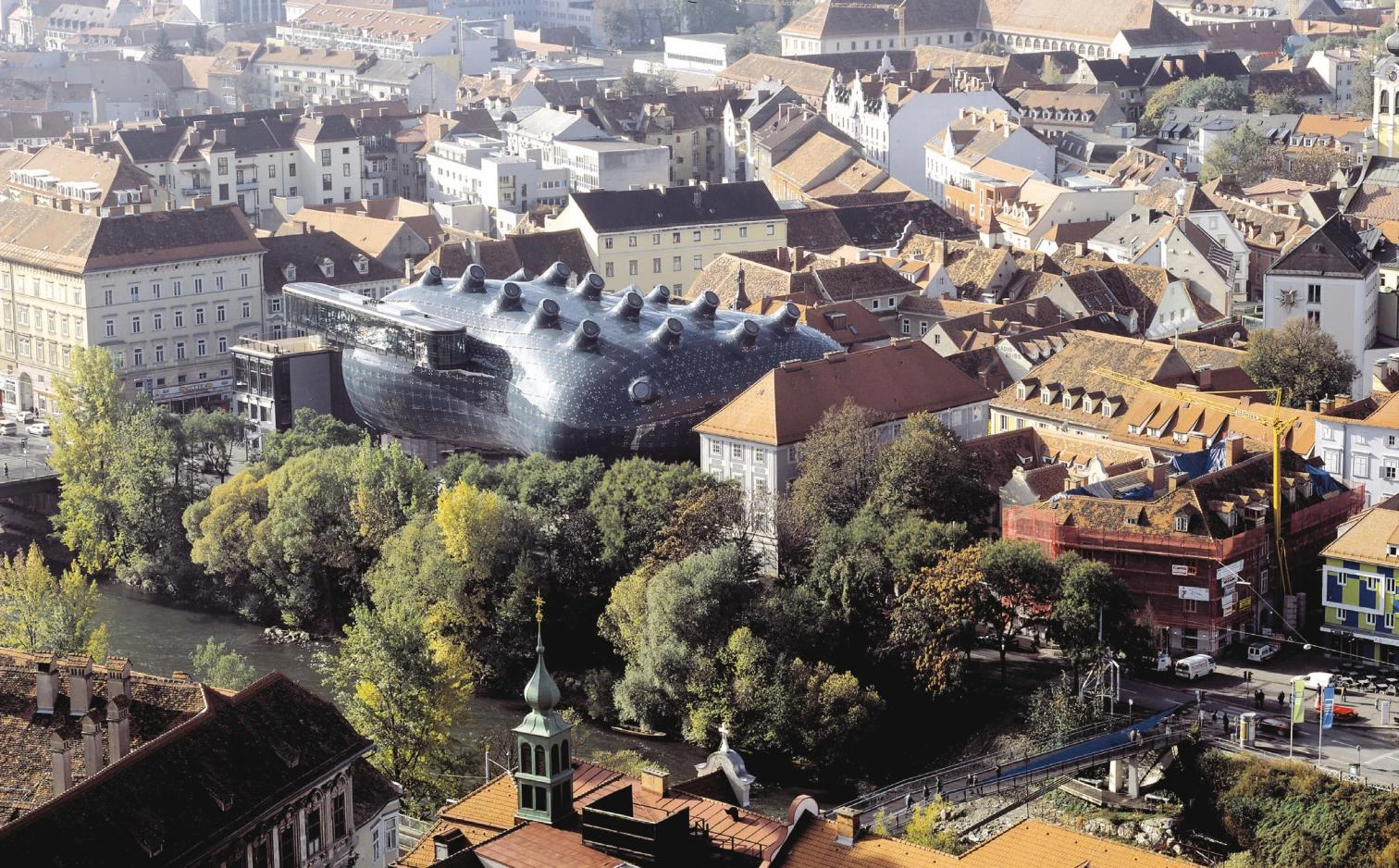

An emblem of urban modernity built to celebrate Graz’s year as culture capital, the bluish bubble materializes a youthful dream of its author, Peter Cook, member of the mythical group Archigram.

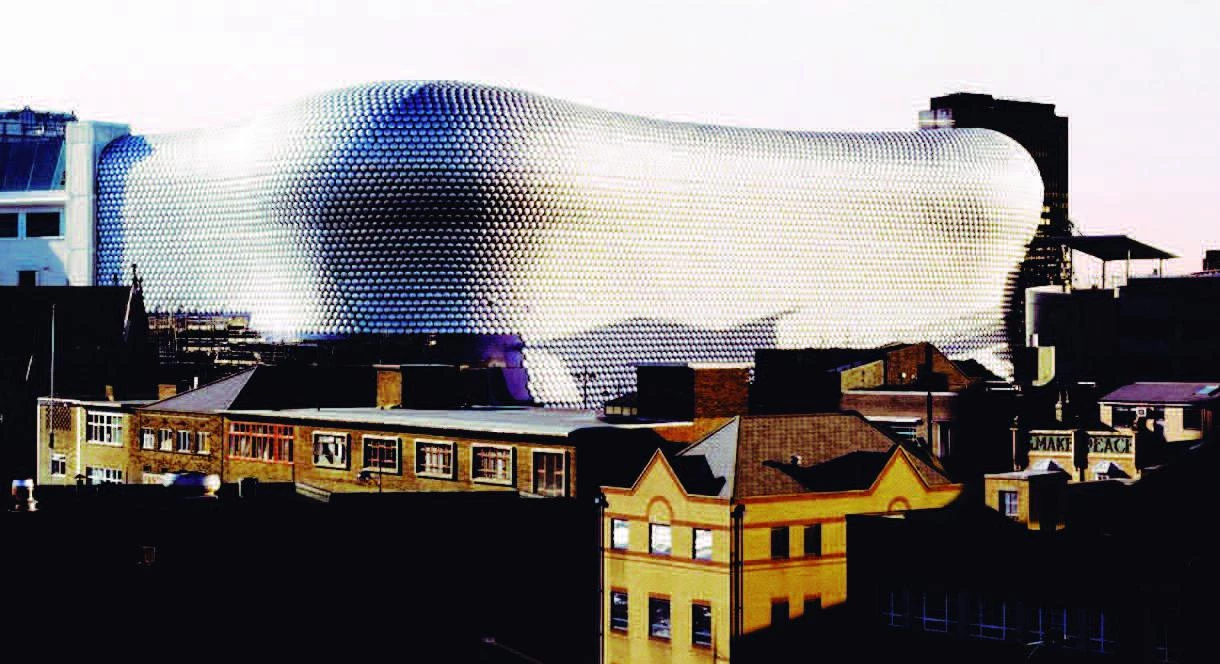

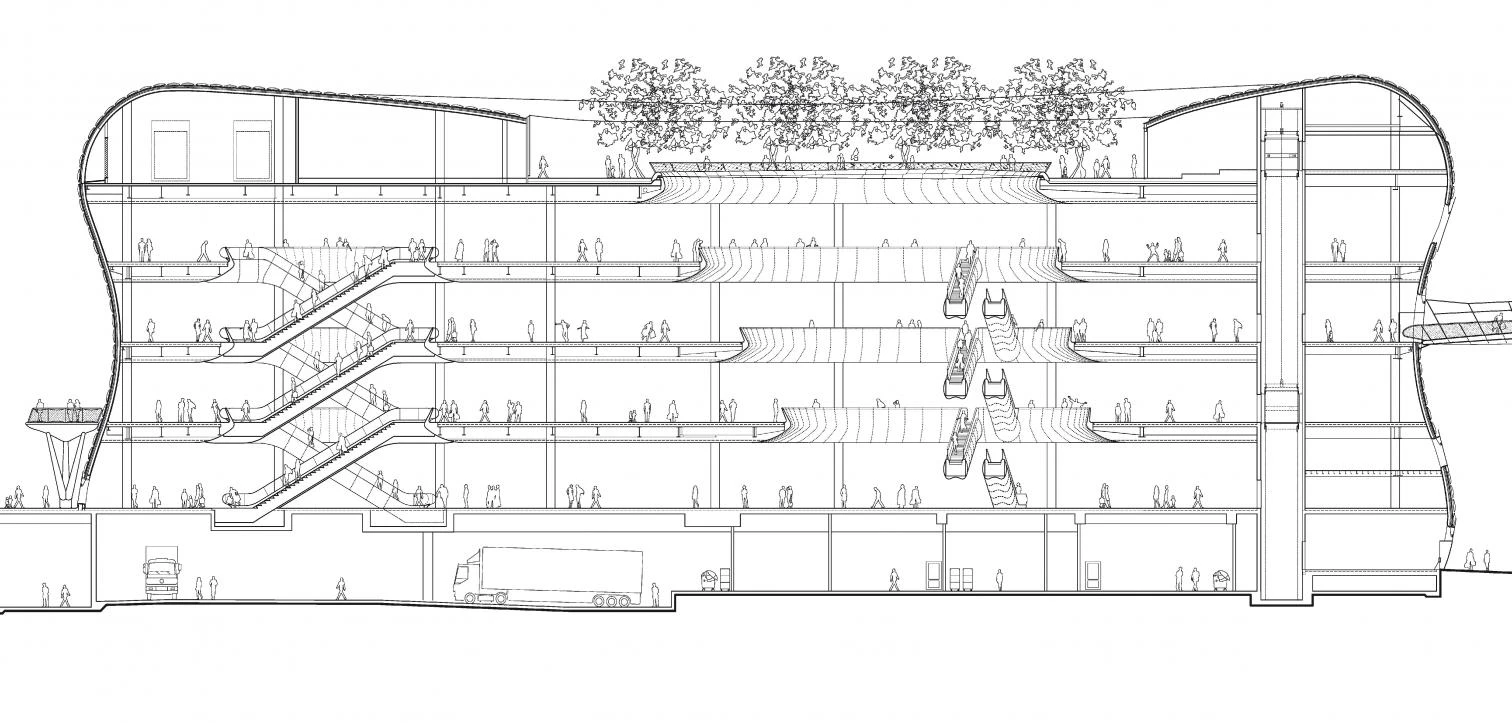

In Birmingham, the company Selfridges wanted to blow oxygen into a decaying commercial type –the department store, subjected for three decades now to the tenacious competition coming from suburban commercial centers – with an architecture that attracts attention, and for this it chose Future Systems, a studio with a programmatic name that situates itself in the wake of Fuller and the Norman Foster who once employed Jan Kaplicky, a 66-year-old Prague-born architect who runs his London office with his wife Amanda Levete. Resuscitating a project of twenty years ago, Kaplicky took thirty-six months to erect a 25,000 square meter building, the largest Selfridges after the historic first store on Oxford Street that the American Daniel Burnham built in 1908. (In line with the policy of using architecture as an advertising billboard, the next store, to open in Glasgow in 2007, has been entrusted to the Japanese Toyo Ito, the same architect who has designed for El Corte Inglés in Córdoba a store shaped like pearlized bubbles.) having sought a flashy, glamorous, seductive effect – something that in recent years has been limited to the boutiques of the great fashion signatures, the Guccis, Pradas or Armanis that have driven department stores out of urban centers and popular imagination – and such desire for spectacle goes on to invade the interior, theatrically thematized with each floor assigned to a different architect.

An emblem of urban modernity built to celebrate Graz’s year as culture capital, the bluish bubble materializes a youthful dream of its author, Peter Cook, member of the mythical group Archigram.

Instant Icons

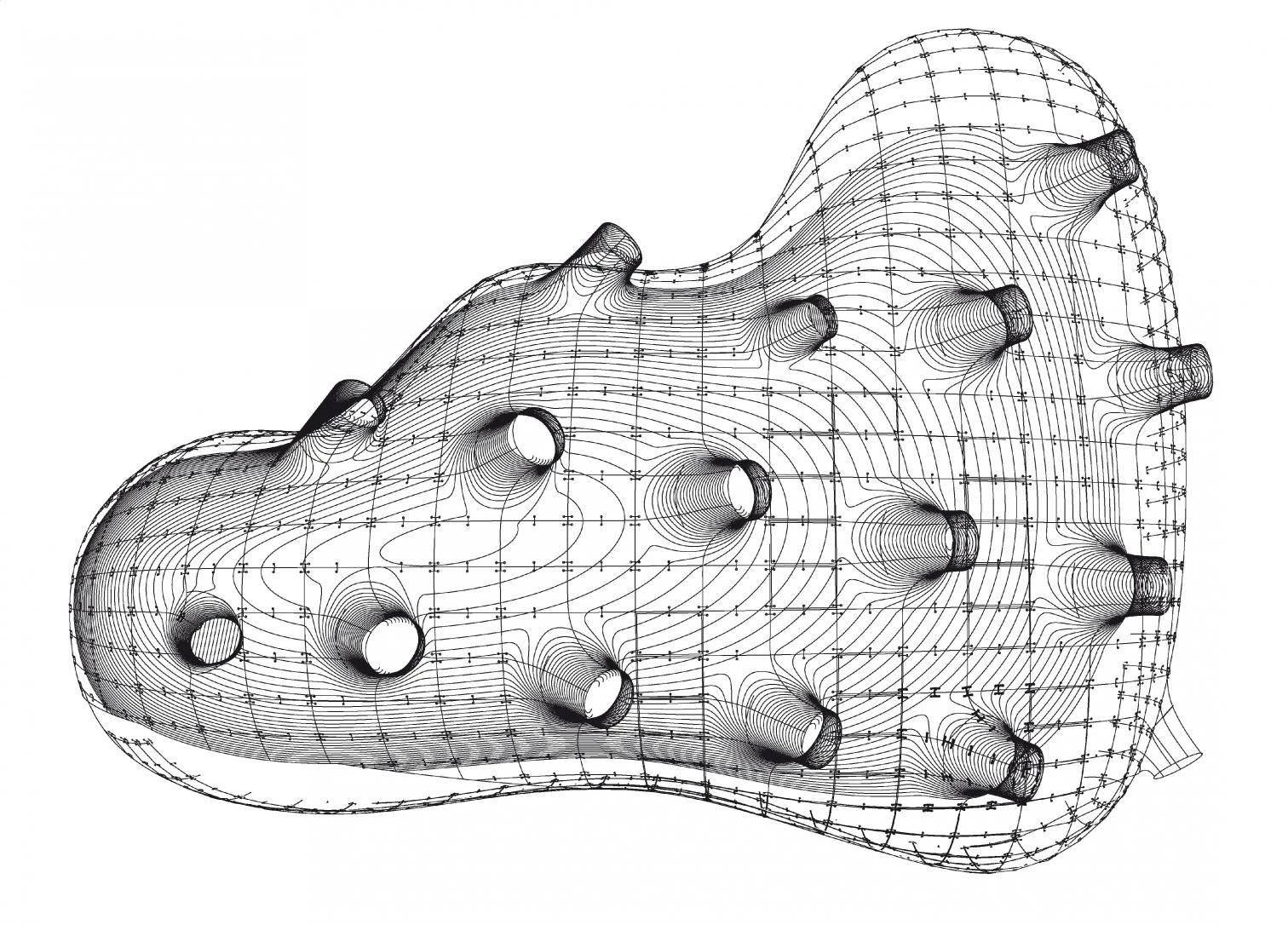

The biomorphic lump of Birmingham rises in the disfigured center of a city devastated both by in-dustrial decadence and the aggressive urbanism of the sixties, but which remains Britain’s second most important metropolis. In this chaotic, amorphous center, in front of a neo-Gothic church, Future Systems has with conventional techniques built an amoebic department store that takes on its characteristic image of a mosquito’s eye or serpent’s skin through 15,000 discs of anodized alumimum fixed like thumbtacks to a concrete shell painted Klein blue: an instant icon for both commerce and the city that recalls Paco Rabanne’s metal sheet dresses of the sixties but also the perceptual explorations of Anish Kapoor, an artist who occasionally collaborates with the architects. With their monumental sculpture rising 37 meters, Future Systems admit to having sought a flashy, glamorous, seductive effect – something that in recent years has been limited to the boutiques of the great fashion signatures, the Guccis, Pradas or Armanis that have driven de-partment stores out of urban centers and popular imagination – and such desire for spectacle goes on to invade the interior, theatrically thematized with each floor assigned to a different architect.

As an antidote for an environment damaged by industrial decadence, Future Systems has designed a departament store shaped as an amoeba, clad with aluminum discs fixed to a concrete shell.

Instant Icons

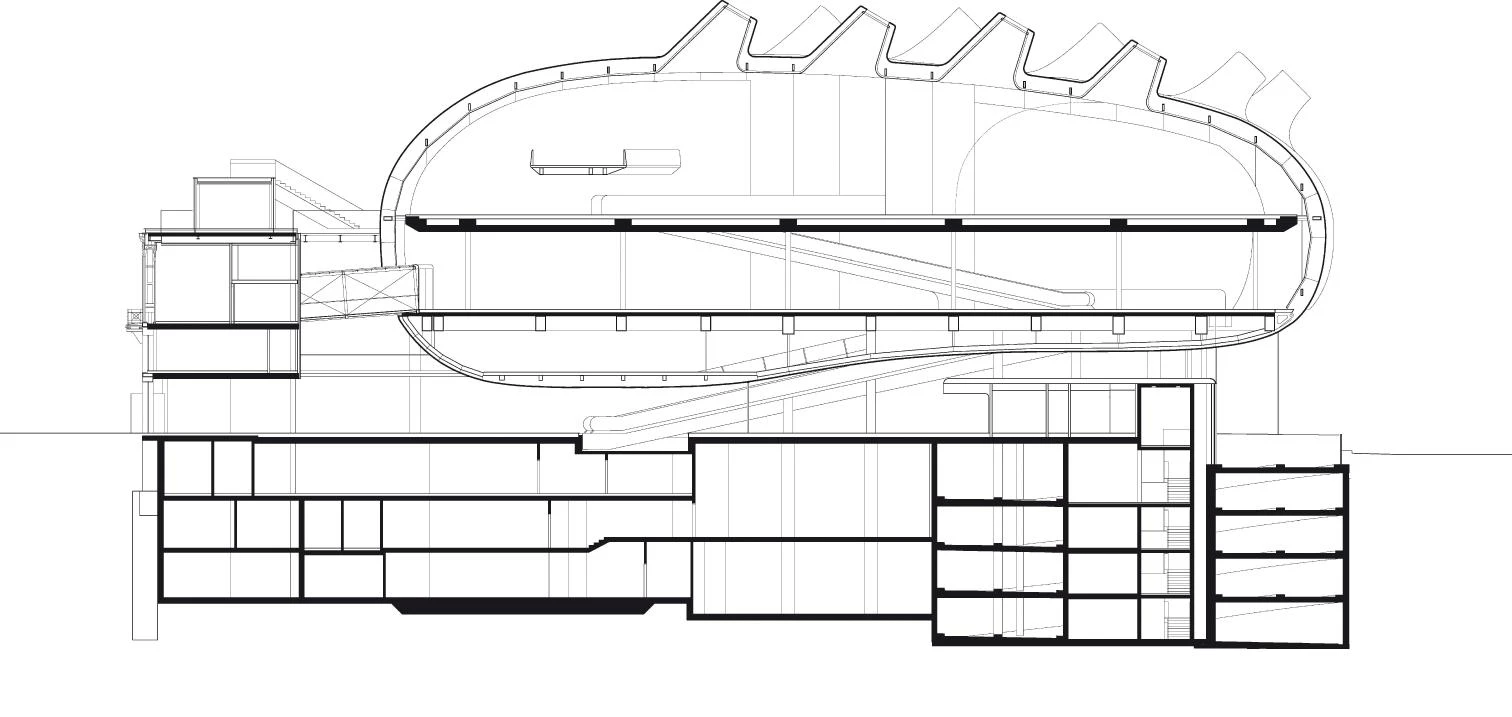

In Graz, an Austrian city of singular beauty and the largest historic urban core of the Germanic world to survive World War II bombings, the veteran founder of Archigram Peter Cook – a Brit born in Essex 67 years ago – and his colleague Colin Fournier have fabricated a local Kunsthaus (dedicated exclusively to contemporary art) as a blue blob bristling with eyes fronting the old quarter, on the right bank of the Mur River. Built with a trian-gulated steel structure to which panels of methacry-late are fixed, and crowned by a profusion of bulging circular skylights that give it the disturbing look of an extraterrestrial organism, the scaly bubble of the Kunsthaus gets its hype on the occasion of Graz’s current turn as European cultural capital, and in its dialogue with the old belfry of the Schlossberg and the city’s other old towers it aims to convey the worn-out message of a collective desire to reconcile avant-garde and tradition.

But in truth, neither the utopian futurism of Peter Cook – an architect exclusively dedicated to teach-ing since the Archigram years – nor the fractured expressionism of the so-called Graz School – an influential deconstructivist group headed by Günther Domenig – has engaged with tradition in any dialogue other than that involving contrast and con-flict. Here, what the architects call their “perverse technological building” has, they claim, a contextual justification: “it’s just another sexy shape, like the bulbous domes of Graz”. More tuberous than bulbous in its resemblance to a flowering potato, this friendly alien of course evokes Archigram comics – abundantly reproduced last year following the group’s winning the RIBA Gold Medal – but it is somehow removed from the visionary élan of the proposals of that period: a truly incandescent time that has been remembered in all its political dimensions with the death, this month of August, of Cedric Price – the most influential critic of those years, author of mythical projects like Fun Palace or Potteries Thinkbelt, and considered by Cook to have been the most important thinker of British ar-chitecture in the second half of the 20th century.

In the largest historic center of the Germanic world, Peter Cook has raised a Kunsthaus whose shape evokes the city’s bulbous domes and whose skin of methacrylate panels is dotted by bulging circular skylights.

It may be because Utopia by definition lacks a specific place, or because visions by nature vanish when they come into contact with reality. The fact is that dreams always defraud. Nevertheless, it is hard to be hard on the late bubbles of these sexagenarian architects. After all, department stores need to attract customers in the same way that art centers must lure visitors. What more, Birmingham is indeed such a calamitous metropolis that any-thing new can only improve it, while the beauty of the old city of Graz will hardly be diminished by astrange lump across the river. Finally, just as the oneiric blob of Future Systems could regenerate urban life and symbolize optimism, the fantastic or-ganism of Peter Cook ought to be able to attract cultural tourism and become an emblem of futuris-tic modernity. They are indeed architectures of con-sumerism and fiction (or science fiction), but the longing for the dreams drawn in the sixties, which is a nostalgia for a younger and more innocent society, cannot erase from the landscape the specters built by the awakening of the ancient avant-garde.