Reinventing Norman Foster

After more than fifty years, Norman Foster’s career is so vast, covering so many types of buildings and so many different parts of the planet, that it is hard to think of as one whole. Nevertheless, the diversity of his commissions and the extent to which they are distributed within the corporate structure of Foster + Partners does not prevent us from recognizing the unmistakable stamp of Foster in any skyscraper, office building, auditorium, or private house executed by this firm.

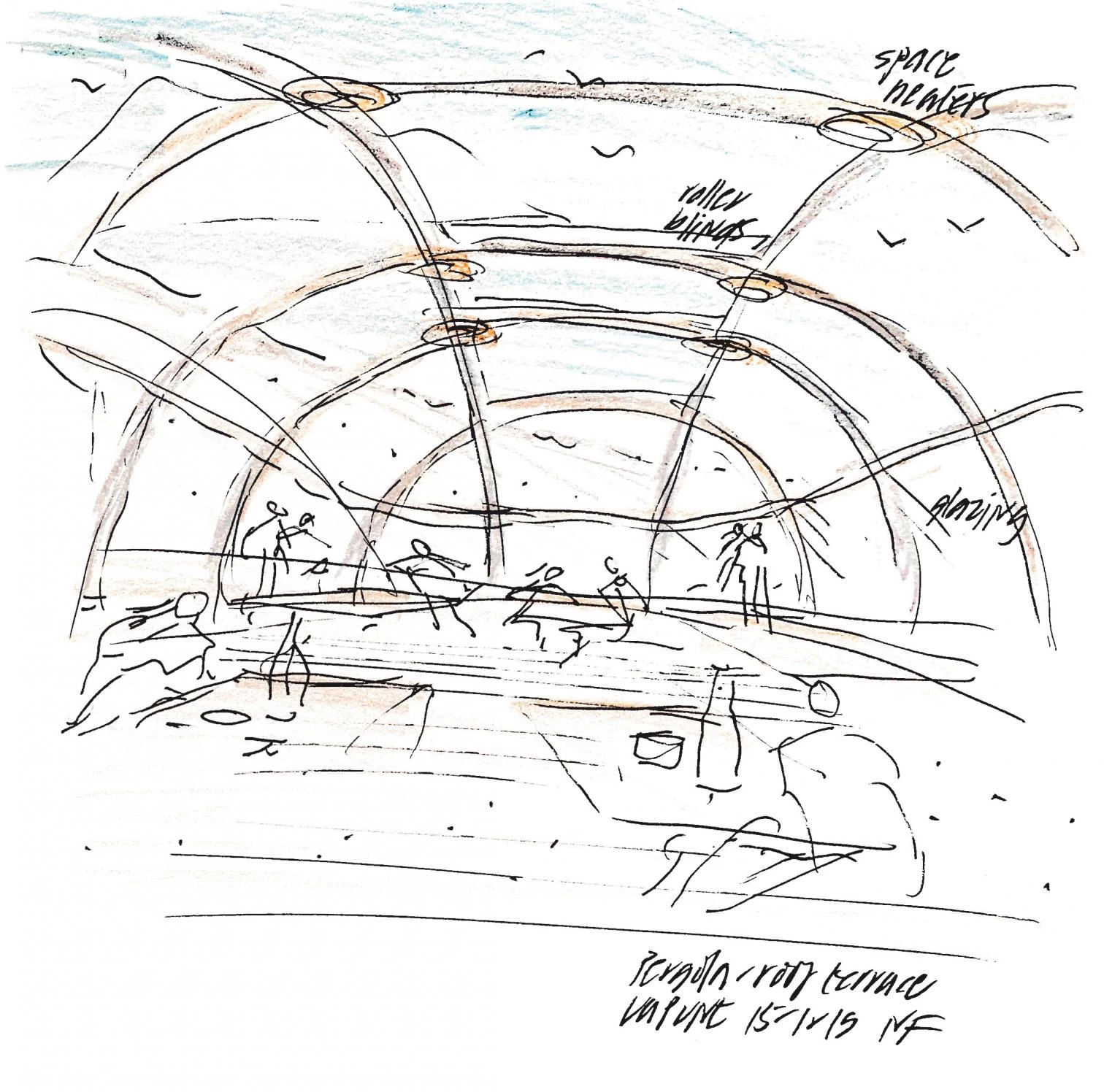

Foster’s stamp almost always involves a brand image carefully devised from certain style elements, certain details, and also certain ways of conceiving and developing the project, including from a logistical and intellectual angle. But sometimes the stamp is perceived immediately, as it reflects the sure strokes that Foster’s left hand leaves on paper, as well as the technological invention and the attention to construction details that are part of his manner of working.

What’s interesting is that the projects Foster seems to have been most closely involved in are perhaps the least predictable among the products of Foster + Partners. Suffice it to think of the typological, formal, and constructional diversity of the most personal among his recent works, from Apple headquarters in Cupertino to Le Dôme winery in Saint-Émilion, or from the Droneport for the Venice Biennale to the Hall of Realms for the Prado Museum.

In all of these, Norman Foster’s intensity leads him to think up projects with a laudable ingenuity that seems to avoid the baggage of an entire career, or at least keep it for a time in a kind of productive unconscious. The result is that they are less an acrobatic demonstration of Foster’s deftness in making the pencil reproduce what he already has knowledge and mastery of, which is a lot, than the expression of a modest and more interesting attitude: the determination to learn from different problems, places, and climates, and to offer the most specific and convincing solutions possible.

Such an attitude and such results come to the fore in InnHub La Punt, the latest work completed by Foster in his beloved Switzerland, which like previous ones carried out there – Kulm Hotel or Chesa Futura in St. Moritz – can only be understood when taken in relation to climate, building tradition, and formal and technological innovation. The severe Swiss winter climate which calls for compact volumes and inclined planes; the typological and constructional tradition of carefully crafted windows and splendid details in timber; and, finally, that inescapable formal and technological innovation, which, funneled through Foster’s special view of the world, ensures that his buildings are never mere imitations of the past but – in truly ‘Fosterian’ manner – admirable premonitions of the future.

Foster + Partners, InnHub, La Punt Chamues-ch (Suiza) © Fotos Foster + Partners