Architecture can build pluralism. In a world shattered by the tension between globalization and nationalism, the built environment can provide stages for this conflict to be choreographed, bridging the gap between the cosmopolitan and the local through dialogue and compromise. The impact of mass migration has altered the social and political landscape of many western democracies, from the United States to the European Union, where the Brexit vote has been the most dramatic expression of the widespread unease that is menacing its institutional cohesion. Identity-based nationalism is on the rise, and plurality is increasingly perceived as a risk rather than as a richness. But political pluralism is the only hope of survival in this sea of troubles, and its privileged scenario is the polis, where top-down policies and bottom-up participation converge. Winston Churchill wrote that ‘we shape buildings, and thereafter buildings shape us,’ and the same could be said of the spaces of the city, which we design only to realize that in the end they shape the forms of our communities, favoring or difficulting the interaction between cultural or ethnic groups. So architecture can build pluralism providing plural spaces, places that promote diversity and create a common ground for our living together.

The Aga Khan Award for Architecture has celebrated these spaces for pluralism in the past, and in fact its very structure is designed to bring into dialogue a plurality of approaches springing from the very diverse geographic or cultural backgrounds. Far from exclusively distinguishing major works from major architects – as is the case of most other architectural prizes – the Award has brought together skyscrapers and mud huts, heritage and innovation, workspaces and museums, urban plans and tiny constructions, iconic buildings by prestigious offices and humble achievements by anonymous craftsmen. This phenomenal variety is further reinforced by the credit given to the many different actors that bring architecture into being: architects to be sure, but also clients, builders, craftsmen, and even the members of the community that take care of the running and maintenance of the building, promoting a perception of the environment as a collective endeavor, where a plurality of interests and voices must be joined in an articulated conversation for the project to succeed. Pluralism is then inscribed in the spirit and the protocols of the Aga Khan Award, and the extraordinary variety of the works selected in this cycle express eloquently this commitment, in continuity with the goals pursued in previous editions, thus exhibiting a remarkable consistency in its already long history.

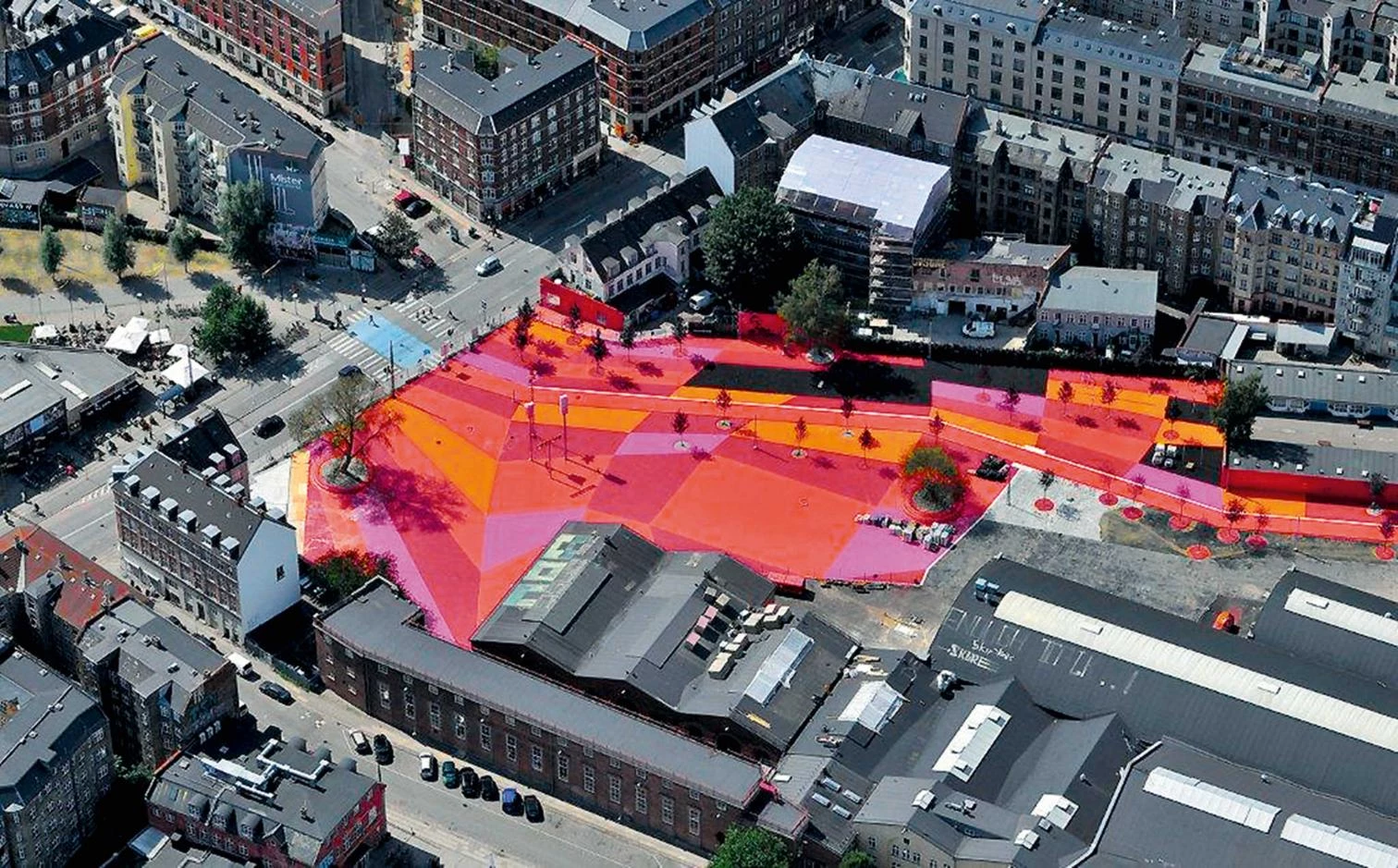

Beyond the pluralism of the Award itself, there are always some projects that manage to embody plurality in an exemplary manner, and this is the case – in the current XIII cycle – of Copenhagen’s Superkilen, an urban park in a socially conflictive and culturally diverse district of Denmark’s capital city. As is well known, the country is so admired worldwide that many consider it a social and political model worthy of emulation, and advocate following its example. Francis Fukuyama, in The Origins of Political Order, goes as far as proposing ‘getting to Denmark’ as the challenge that most democracies face today, perceiving the Scandinavian country as a particularly successful institutional arrangement that deserves being a beacon for others. However, of late, the lack of integration of different immigrant cultures has created significant tensions in Danish society, exacerbated, since the cartoon controversy in 2005, with widespread Muslim unrest and the unhappy rise of xenophobic, populist movements. In this context, the completion of the Superkilen through the combined efforts of the architects of BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group), the landscape designers Topotek and the artist group Superflex is a colossal achievement, because it faces head-on, with stupendous imagination and user participation, the current dilemmas of immigration-shocked European societies, and finds an answer in pluralism.

At this point we should probably point out that pluralism and multiculturalism are not interchangeable terms. Multiculturalism has a bad press these days, after the failure in many contexts to sustain an archipelago of different cultures, coexisting as self-sufficient islands, and the German chancellor Angela Merkel, so courageous and generous in her attitude towards immigration, did not hesitate to concede that what many call multikulti had not really worked. But the reaction to this failure need not be (as nationalist, jingoist movements often defend) the imposition of a single culture in each country; on the contrary, the cultural diversity of immigrants can be understood as a richness that can flourish under a pluralist system that does not isolate different backgrounds and experiences in ethnic enclosures, but rather allows cultures to cross-fertilize through contact and conversation, recognizing the relativity of each world view and solving conflicts with the tools of dialogue and trust. This is exactly what the Superkilen project has been able to achieve, transforming a dangerous area into a mix of amusement park and world fair of urban objects curated by the neighbors, thus becoming a cherished space for the plural communities on both sides of the ‘kilen’ – the wedge – and a tourist destination in the city.

In a country now sadly tarnished by Islamophobia – no different from the deep xenophobic, anti-immigration currents that are slowly eroding the foundations of the European Union, but which here have violently come to the surface with the anti-mosque campaigns of the Danish People’s Party – Copenhagen’s Superkilen is a phenomenal antidote, creating public space for diverse identities, highlighting plurality and addressing political conflicts and social controversies with the weapons of bold creativity, daring humor and participatory design, thus knitting a web of emotional connections that gives a sense of belonging, empowers the community, and endows everyone involved with a feeling of pride.

If architecture can breed pluralism, surely this is a fine example that should inspire others. The aesthetic imagination and social awareness shown by Superkilen is a tribute to the architects and artists who designed it with the residents, and also to the clients, the City of Copenhagen and the philanthropic association Realdania. And the extraordinary success of the project is living proof that pluralism in the built environment can and indeed should be a guiding thread in the labyrinthine paths that open up ahead of us in these troubled times.