Economy colonizes language, and homes today are essentially properties. Both in the real estate supplements of newspapers and in residential reality-shows, dwellings appear as containers of savings and of dreams, presenting the house as the main aspiration of a family and its lifetime investment. The physical and financial solidity that a house promises, however, is not backed by data. As The Economist documents in its report ‘Bricks and slaughter’, what many consider to be the stablest investment is in fact inherently unsafe, fragile and volatile. The dimension of the risk comes from the huge size of the sector – more savings are devoted to housing than to stock or pension funds –, its high level of debt and the perverse mechanisms that stress the cycles of growth and fall, both in the case of banks that give mortgages and in that of individuals who consider housing at once a consumer good and an investment.

The real estate cycle has never been a virtuous circle, but the latest bubble reached unprecedented heights, and its bursting significantly damaged the financial system that supports these architectures of debt, whose toxic capacity reaches an extreme when loans – as is frequent in Spain – are given to developers with no other guarantee than a plot of land of uncertain value. But even when aware of how lethal debt can be, real estate still exerts an equivocal fascination on people, who consider the house not a plain and functional place to dwell, but rather a space for individual expression, a tool for social affirmation and a financial investment. Even though a rational analysis advises renting instead of buying, property prevails in Spain or the United Kingdom, but also in the United States or China; only countries like Germany or Switzerland have social habits and institutional practices that make renting more popular.

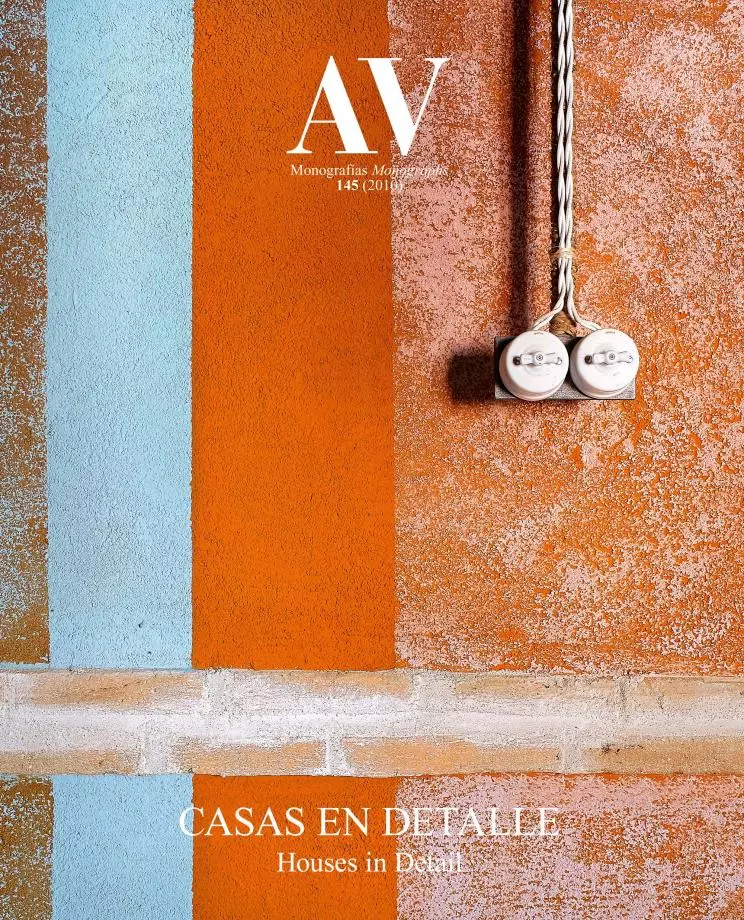

In the end, the decision to buy a house is to a great extent emotional, and the desire to personalize and enjoy it is closely tied to the investment bet, an appetite for risk that fuels all real estate bubbles. A veteran observer of these, Robert Shiller, claims that they resemble sex, because they attract with the same combination of danger and pleasure, so that even the most reluctant end up trying. This is good news for architects, whose current journey through the real estate desert must lead to the promised land of the next bubble. While it comes (and it will take its time, because there is a huge built stock awaiting clearance), and until we finally decide to build dense and sustainable cities, departing from the exurbs where so many superfluous houses go up, those published here hope for the subdued classicism of the congruence between the parts and the whole, and look for God in details. May they find him.