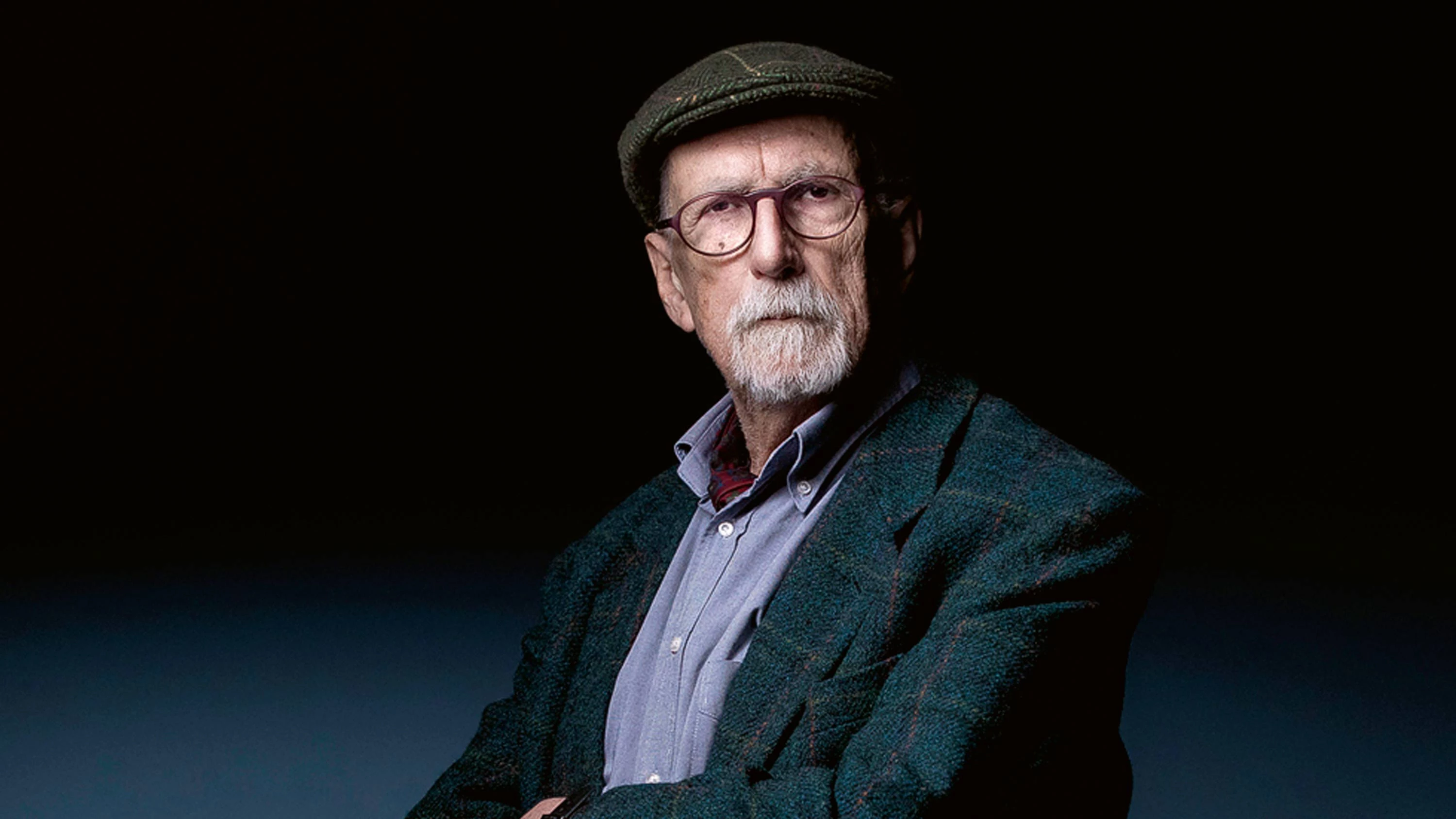

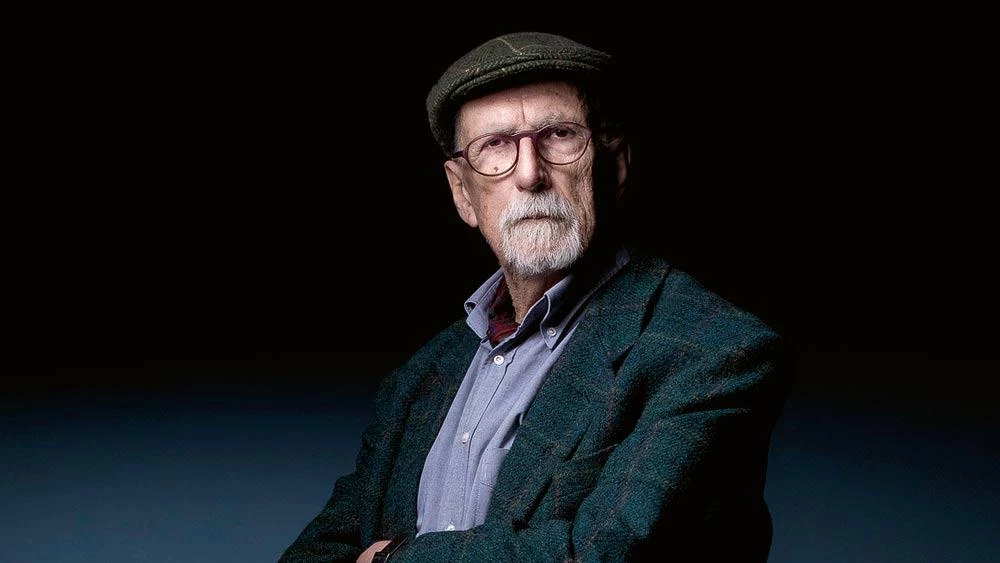

Bruno Latour was one of the last specimens of a species on the brink of extinction: the intellectual. To be precise, a specimen of a class of that species: the French intellectual. And to pursue the taxonomy further, a specimen of a more slanted, confused, and perhaps more dubious subclass: that of French intellectuals whom architects like, and who manage to infiltrate into the congresses and magazines of the discipline.

In this Latour was not the first, but more like the last or next-to-last link of a chain of French thinkers who wielded influence on architecture. A chain which had begun with Bachelard and Merleau-Ponty in the times of phenomenology and existentialism, continued with Foucault and Barthes in the years of structuralism and semiotics, and ended up connecting with Derrida and Deleuze when deconstruction and posthumanism became fashionable.

If Latour was not the first in the genre of French intellectuals that architects take an interest in (for a while), he was in fact among the first to accept with lucidness the intellectual implications of one of the great problems of our times: the environmental crisis. He did so with a detached but committed perspective, equally removed from New Age romanticism and Trumpian denialism, and resting on a controversial pronouncement: “we have never been modern.” ‘Modern’ in the sense of having overcome the two Platonic dichotomies that in his view structured Western thought: object against subject, society against nature.

For Latour, the problem with dichotomies was not only that they were not seen for what they, as he saw it, really were: ideological hindrances. More importantly, they made us incapable of giving serious thought to the new problems that contemporary societies ought to address. Problems having to do, precisely, with things that are hard to associate with any of the two poles of classical polarity. For example, a laboratory-made virus, the ozone hole, robots, the reheated atmosphere… Things which are neither pure artifice nor pure nature, but something in between. Things which, with Tolkienian humor, Latour assigned to the ‘Middle Kingdom,’ the realm of the hybrid.

Reflecting on the hybrid (the intolerably interconnected, the real) was the purpose that Latour pursued in the books he published over the course of his long and polemic career, from his rather unreadable studies of scientific methodology or the We Have Never Been Modern (1991) that made him famous to the later more essay-like and decipherable texts (Latour eventually came to be a good writer), such as Down to Earth (2018), where he analyzed the political implications of climate change, or After Lockdown: A Metamorphosis (2021), something like a version of Kafka’s Metamorphosis, where the insect, waking up after the Covid nightmare, is all of us.

With his peculiar jargon, Bruno Latour in these books urged us to distinguish less between subjects and objects than between ‘humans’ and ‘non-humans’; to be aware of the ideological and even political dimension of all human disciplines; and above all to ‘resituate,’ ‘reset,’ or ‘land’ on a close-at-hand plane the fragile and slightly flattened sphere that we inhabit.

Cryptic in and of themselves (our subject was after all a French intellectual), Latour’s terms have often been distorted and banalized, especially when they have fallen into the hands of sociologists, journalists, and architecture professors. Notwithstanding, this does not diminish the worth of Latour’s essential message, which becomes crystal-clear once it is rid of technicist adornments: there is only one world below the atmosphere, the world that we live in and to which we are profoundly, inexorably bound. Hence our responsibility, our duty, to take good care of it.