Past Present

Transformations of Industrial Heritage

Heatherwick Studio, Zeitz MOCAA, Ciudad del Cabo (Sudáfrica)

We are living in interesting times, and the vanishing into thin air of previously solid certainties applies also to architecture. The situation of architects proliferating and in precarious employment conditions, of competition systems dying out, and of work models in flux is aggravated by a reality which those who practice and teach architecture struggle to assimilate: the fact that nowadays, the objective of their profession is less to build on a clean slate than to build on the already built.

The West is old, and in the material sense too. We give ever more importance to heritage, and a good number of the constructions that 20th-century developmentalism gave rise to have become obsolete, whether because they have lost their original use or because time and its sister, entropy, have corroded their facades, pavements, and structures. Hence, to a large extent, thinking up architecture today is thinking up architecture of the past.

The first batch of heritage interventions had to do with monuments on the grand scale: cathedrals, monasteries, palaces, and cities. At present, the job of thinking the past extends to the much wider field of lesser monuments: pragmatic buildings that stirred up the ambitions of their times, but now are not worth enough to even serve their original purposes, let alone garner the consensus required to be considered unquestionable monuments.

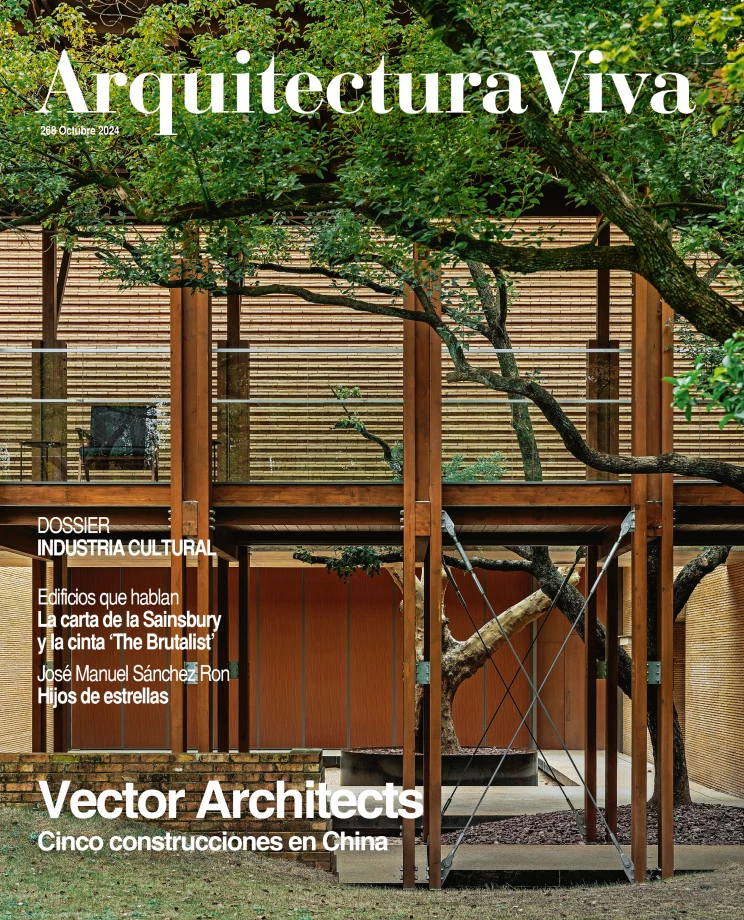

To this monumentality on a minor scale belong industrial buildings, which are often powerful in form but, due to their size or specificities, tend to resist functional transformation. So it is that, in general, the solution for them has been to convert them into cultural containers. Not only because their huge spans and spaces are well suited to contemporary art and the current penchant for flexible, changeable premises, but also because their atmospheres, materials, and geometries in themselves allude to today’s broader sense of the term ‘culture,’ which is no longer as much about museums and art galleries as it is about buildings that speak of a certain way of regarding the world. And what beats a factory in expressing certain values?

The power to evoke and such capacity to include the present in the past are characteristic of the European works we have selected for this dossier. The first, by Mestres Wåge, Mendoza Partida, and BAX studio, involved making an art museum out of a silo that Arne Korsmo, pioneer of functionalism, built in Kristiansand (Norway). The second, by Prokš Přikryl, created a cultural space in the robust Automatic Mills raised by the ‘cubist-rationalist’ architect Josef Gočár in Pardubice (Czech Republic). And the third, by Assemble and BC Architects, turned an old complex previously used for manufacturing train machinery into a laboratory for circular design.

Harquitectes, Centro cívico Cristalerías Planell, Barcelona