Living Monuments

The Challenges of Heritage

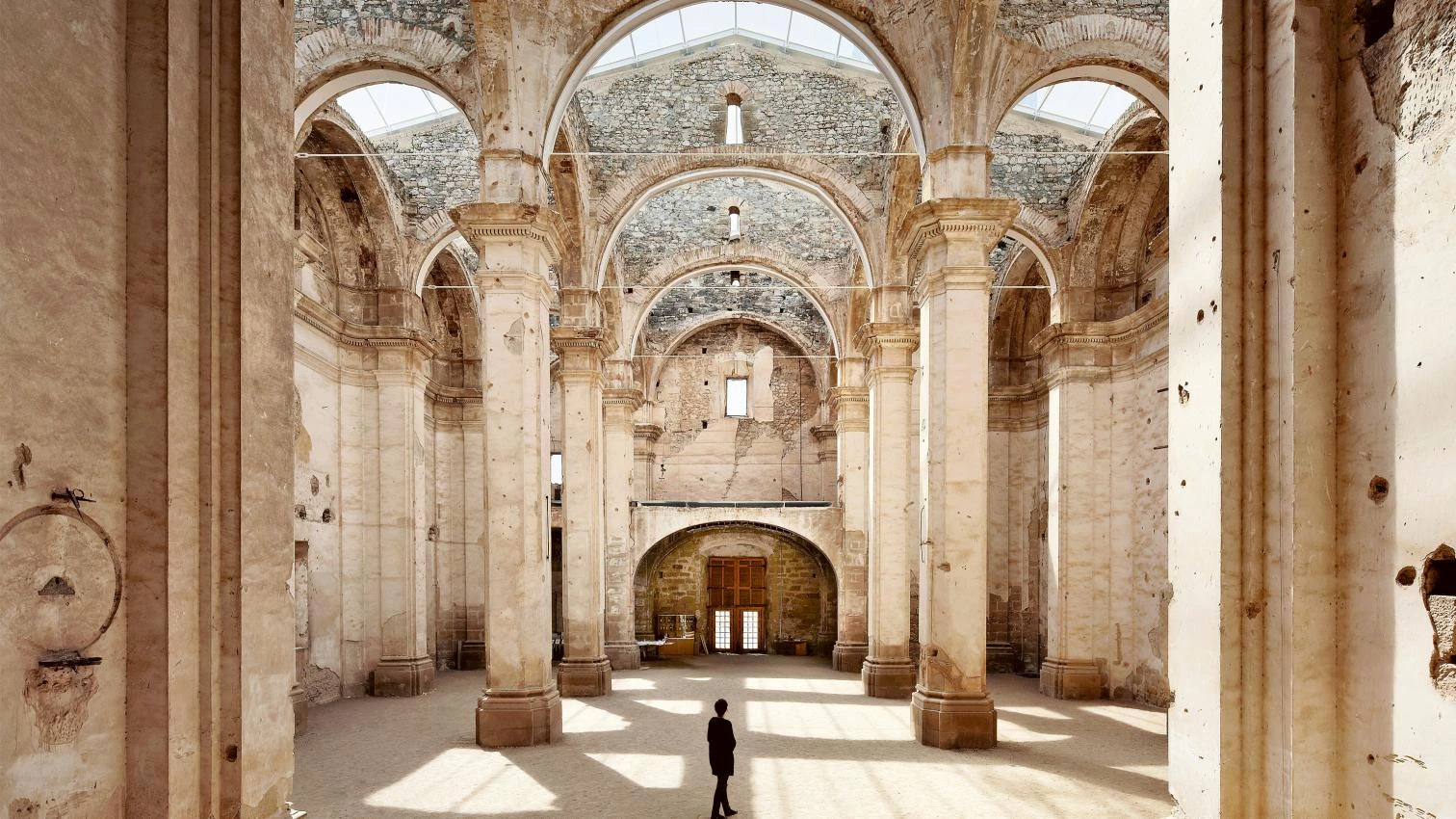

Building over the built is a modern problem. Before the existence of historical perspective, remains of the past – even the most prestigious remnants of classical Antiquity – were treated as dead matter that, when left at the mercy of the elements thanks to pillage or demolition, could without pangs of remorse be used to raise new buildings. As long as there was no remorse in the conscience of the general public, the legacy of the past could not be turned into ‘heritage’; that is, no resources would be allocated to protecting buildings whose value did not lie in their function, nor necessarily in their beauty, but simply in their being depositories of time. But once the concept of sentimental historical perspective took root, there was no stopping the advance of protectionism, and it became difficult to prevent the idea of monuments as crystallized history from giving way to that of monuments as mythified – when not altogether sacralized – history.

Perhaps because we look for stable references in a world increasingly shaken by change, current sensitivities tend to consider everything a nugget of patrimony, material and immaterial things alike, and in this paradoxical eagerness to preserve history by abstracting it from history itself lurks the danger of preservation becoming more and more dogmatic. Even in what concerns the work of architects, where for some years now we have seen a disturbing propensity to leave heritage buildings exclusively in the hands of specialists, as if the mere fact that a construction has gone through the filter of history made it something different from architecture.

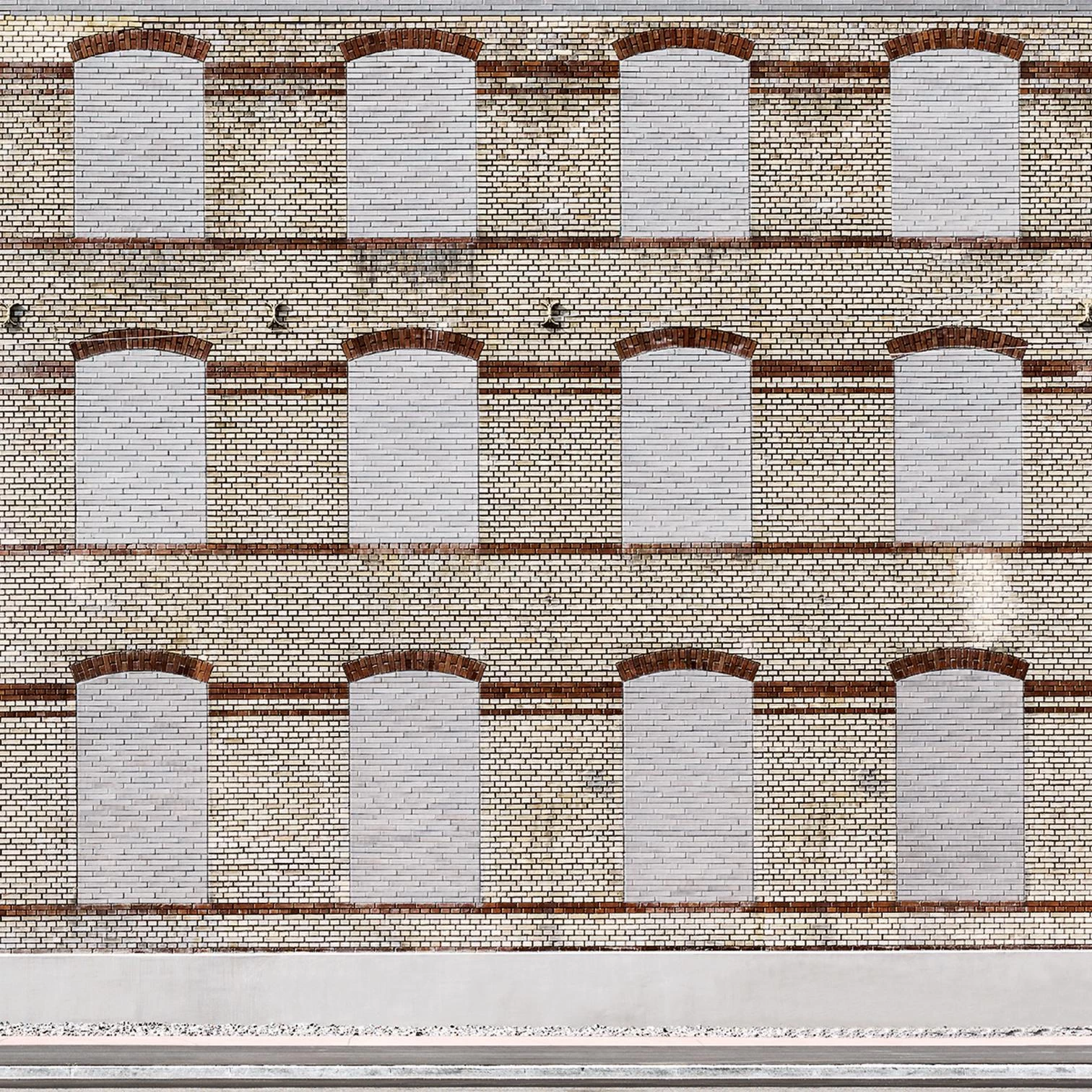

The four interventions featured in the following pages are not dogmatic. They take root in the contemporary, refusing to treat vestiges of the past as objects doomed to be revered, as in a museum. And instead of being entrusted to specialists, they were assigned to architects who know how to handle relics: carefully but never in total subservience. Such is the case in the transformation of the Victorian-era coal warehouses located at King’s Cross in London, where Thomas Heatherwick has connected two old pavilions with a sweeping warped roof over an attractive new public space. Another is the restoration carried out at the Tai Kwun Centre in Hong Kong, where over a colonial-era police station and prison building Herzog & de Meuron has superposed a sophisticated prism clad in pieces of recycled aluminum. The same inclination to create something new out of history is evident in the project executed in an area of China that is known for its coffee trees, where TAO Architects has masterfully combined traditional brick vaults with mighty portal frames of reinforced concrete, as well as in the revamp of the Sant Antoni Market in Barcelona, which Ravetllat Ribas has used as an opportunity to transform the urban environment.