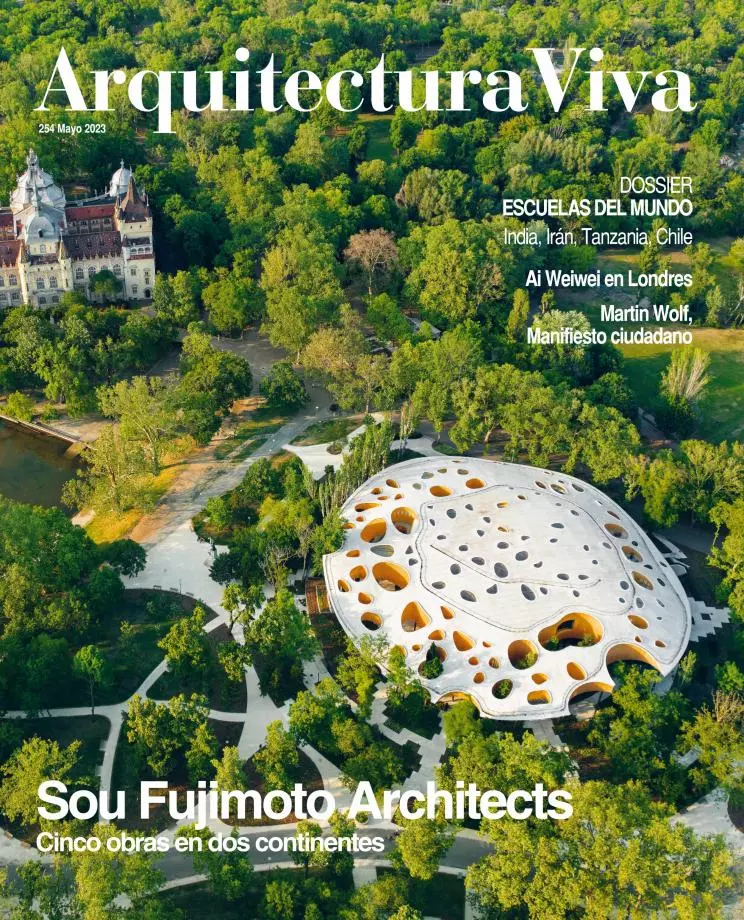

Guadalquivir marshes © Héctor Garrido

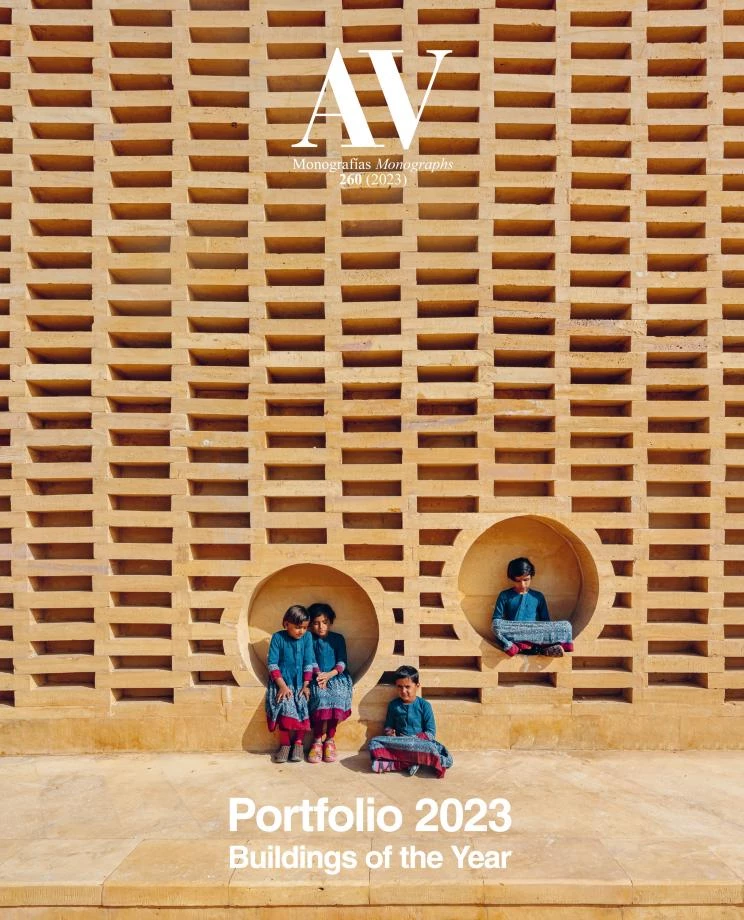

The landscape is a product of human action. We do not know what the future of the environment shaped by climate emergency will be like, but we do know that those landscapes will be defined by deliberate choices. Haiti’s deforestation contrasts with the protection of the forests in the Dominican Republic, and the border between the two countries is a clear environmental and political statement. With the start of the warm spring of 2023, the Panel on Climate Change published its sixth report, the dramatic conclusions of which must serve as basis for the COP28 to be held in December in Dubai: a UN summit that will hopefully acknowledge the urgency of the moment, after the disappointing COP26 of 2021 in Glasgow and COP27 of 2022 in Sharm El Sheikh. Three decades have passed since the first meeting in Berlin, and only the COP21, which led to the 2015 Paris Agreement, seems to justify the effort of reviewing research and gathering experts and politicians to set the mitigation and adaptation measures this planetary challenge demands.

But along with climate, which is the center of the debate, biodiversity deserves to be mentioned as another influence on landscape, and another cause for alarm. Both issues were the subject of agreements at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, and both have been developed via Conferences of the Parties (COP) which, through their acronyms, have spread from the bureaucratic language of international organizations to general media. However, while climate COPs get huge coverage, biodiversity COPs go almost unnoticed, and the COP15 held in December 2022 in Montreal has not received enough attention, even though its agreements to guide global action are indeed historic. Presided by China and organized by Canada, the conference adopted the Kunming-Montreal Framework, which proposes to protect 30% of the planet and to restore 30% of degraded ecosystems by 2030, and with that 30x30 objective the UN approved in March the High Seas Treaty, which protects that percentage of international waters.

The COP15 framework also aims to reduce the loss of areas of high biodiversity and ecological integrity, and that includes Spanish wetlands like Doñana, Tablas de Daimiel, Ebro Delta, Albufera or Mar Menor, which should be protected with wide agreements to leave them out of political struggles. Those biologically rich landscapes have been shaped by geography and climate, but also by human intervention, and if both global warming and droughts as well as the impact of the exploitation of aquifers and agricultural activity put them at risk, it must be our collective decision to establish priorities. Many of us discovered the violent beauty of the fractal landscape of Doñana’s marshes with a movie shot there, La isla mínima, and we know that the protection of these areas is a biological objective, but also an aesthetic one: the deliberate landscapes of our common future will be a voluntary geography that reflects our ethic responsibility and, in equal measure, our commitment to protect beauty.

Border between Haiti and the Dominican R. © PNUMA