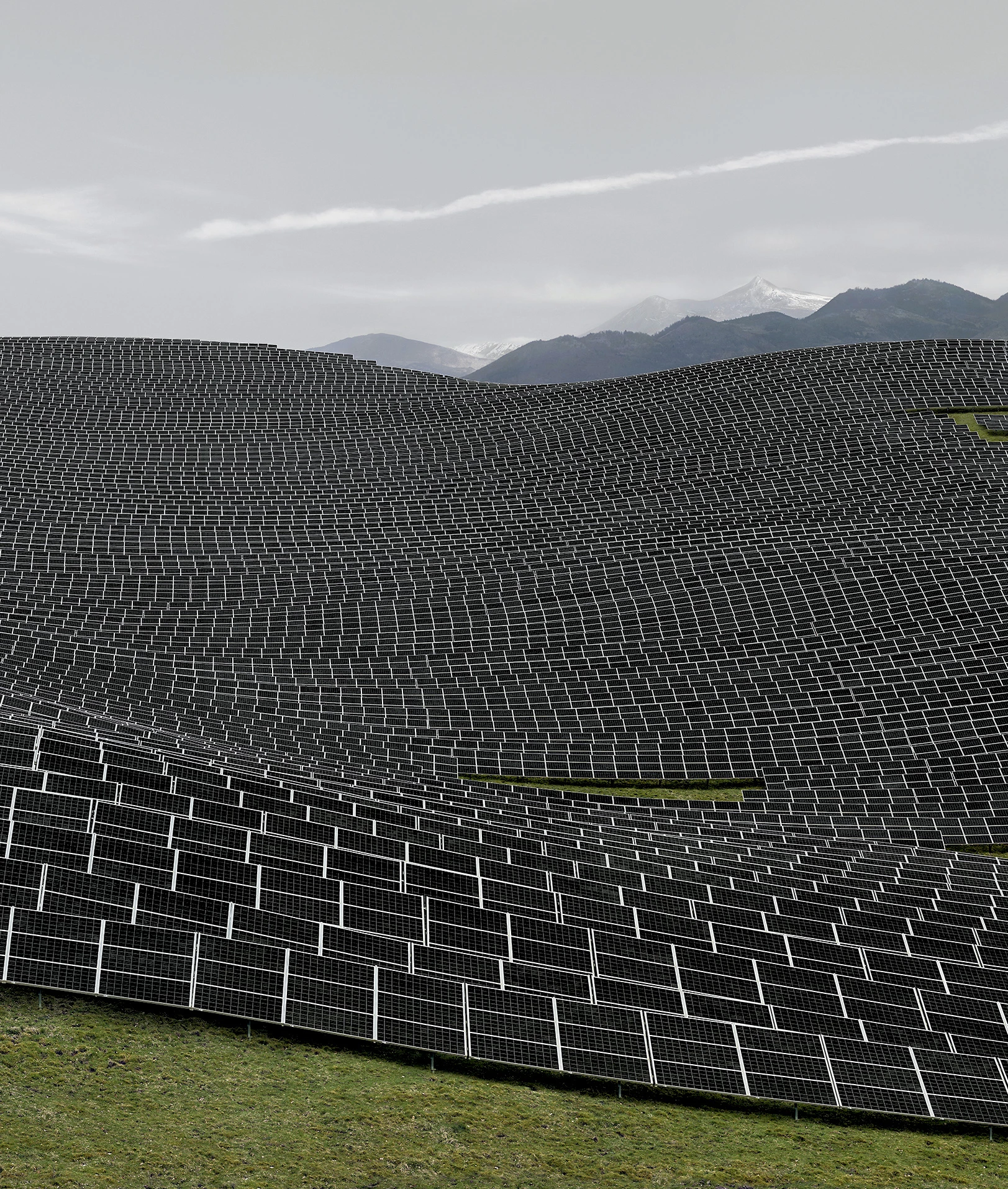

Andreas Gursky, Les Mées, 2016 (France)

The landscape is a voluntary geography. The idyllic vision of landscape as intact nature is denied by experience and memory. Shaped by economic, environmental, and cultural forces, the planet’s panoramas are not the mere result of geology, botanics, and climate: in fact, they are shaped by history, and are themselves documents that record the political, legal, and social mutations taking place over time, as the historian William George Hoskins explained pioneeringly in The Making of the English Landscape, a book that in 1955 transformed our perception of landscape. Five years before, in Der Nomos der Erde, the jurist Carl Schmitt found the foundation of justice in ‘the law of the land,’ and while that mythical vision today inspires ecologists who defend the recovery of ancestral landscapes, our current challenge is rather about making them productive and sustainable.

When human action is causing the melting of glaciers or polar icecaps, it seems useless to talk about anthropized landscapes as opposed to virgin lands, because we, inhabitants of the Anthropocene, know that no territory is spared our impact, often described in catastrophic terms because of its unwanted consequences, but in origin motivated by the desire to use the environment in our benefit. There is no other way at a time when the climate emergency calls for decarbonizing the economy, a global challenge that will cause the metamorphosis of many landscapes. But the Green New Deal does not lead to garden-cities and bucolic fields, but to compact and complex cities, and to territories where solar collectors and windmills harvest renewable energies: barely green therefore, and immune to the ‘chlorophyll ideology’ that sociologist and urbanist Mario Gaviria criticized.

We like to think that the aesthetic perception of the landscape has its origin in Petrarch’s ascent of Mont Ventoux, but it certainly has roots in Greek and Latin pastoral poetry, from Hesiod to Horatio, by way of Virgil, who described “gelid fountains, soft meadows, groves.” This sublime or pleasant vision, in contrast to that of the landscape as wild nature or shelter from the city bustle, extends to the “disdain of court and praise of village life” that feeds disurbanist utopias and neo-rural movements, but excludes the views of that hinterland as the main deposit of the flows of food and energy that make urban life possible. And at this historic turning point, at which we must reanimate economies in a coma induced to stop the coronavirus from spreading, nothing is more urgent than the construction of the landscapes that make possible the energy transition of the Green New Deal. Even if they are not green.