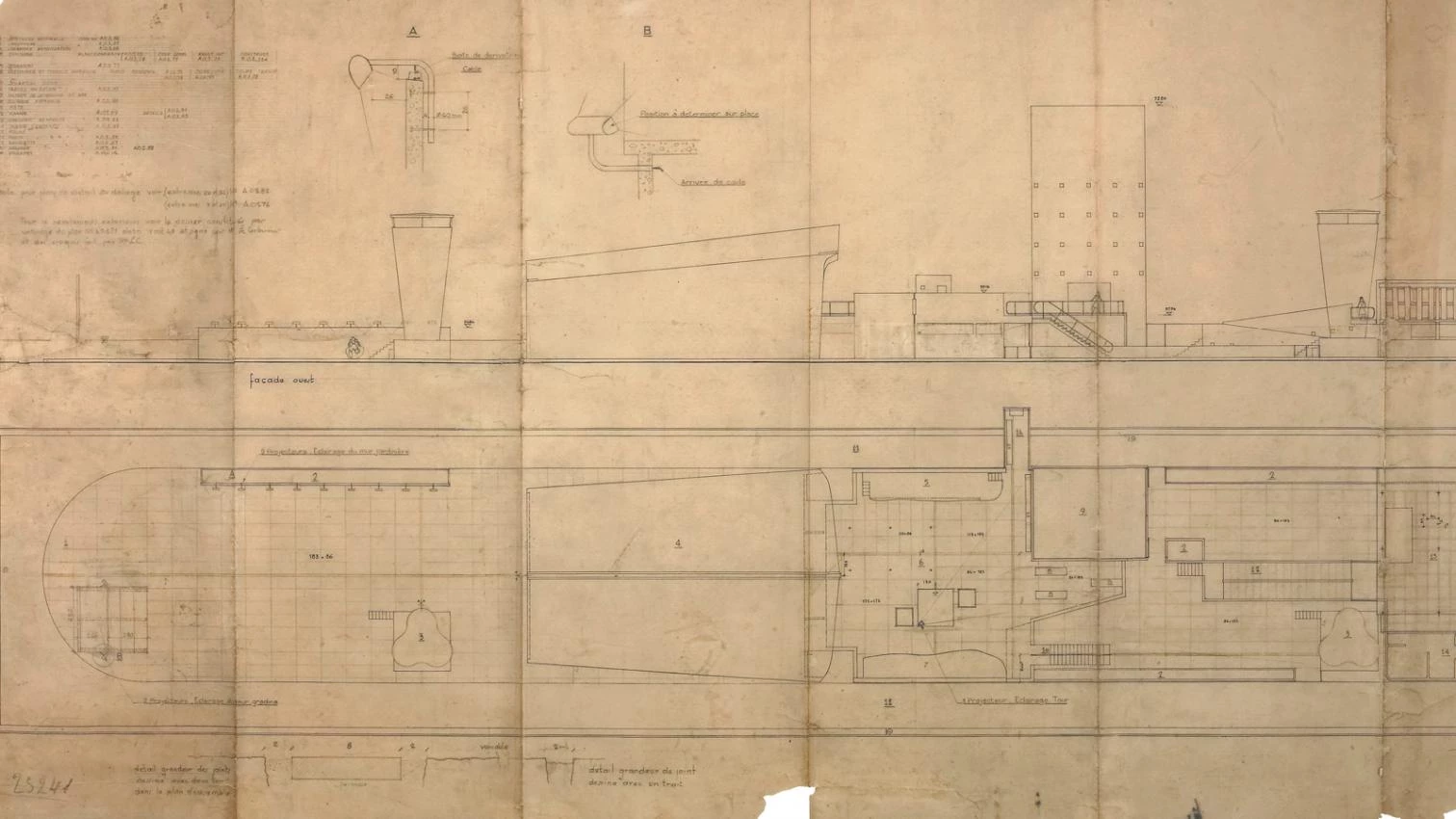

Marseille: Unité dHabitation, a Geography

When Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation (1947-52) was built, set against the undulating profile of the hills around Marseille, it stood tall and erect among a scattering of suburban houses and low-rise apartments. The assertive verticality of this block of flats, located on one of the broad avenues leading out of the city in the direction of the Calanques, a mountainous coastline now designated a national park, recalls one of the tropes commonly used to describe the relationship between human beings and nature: the opposition between vertical and horizontal. In a lecture transcribed in his 1928 volume Une Maison, un palais, Le Corbusier fixed on this duality: It was La Palisse who explained that the eye can only measure what it can see. It does not see chaos, or rather it sees things badly in a chaotic or muddled environment. Immediately, it seizes on shapes. We are brought up short, fascinated, measuring, evaluating this geometric phenomenon which has presented itself: rocks upright like menhirs, the absolute horizontal of the sea, the meandering beaches. And the magic of relationships transports us to the land of dreams.

He illustrated this passage with photographs of the Breton coastline and an Alpine landscape. Some years later he took a photograph in Brittany precisely capturing this sensation. A similar analysis was made in his lecture “Architecture in Everything, City Planning in Everything,” given in Buenos Aires in 1929, in which Le Corbusier went straight on to discuss the Parthenon. Nature was a force to be negotiated and contended with, he declared, as can be seen with the classical temples on the Acropolis that dominate the landscape...[+]