We all know Paris. We all suffer for her ills. We are nourished by what she stands for in terms of history, tradition, instruction. We are ready to take up her situation with a respectful devotion and without sacrilege.1

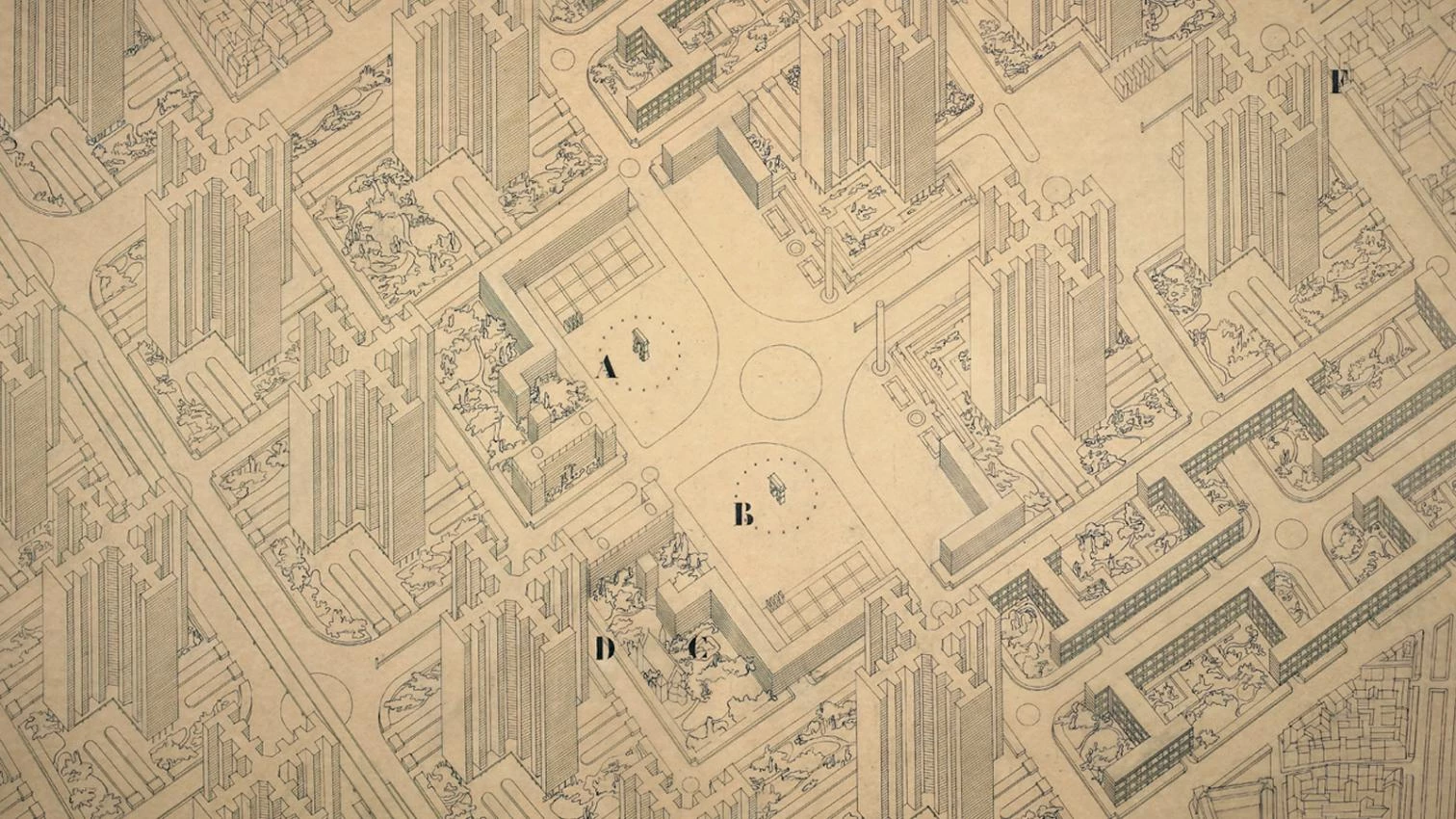

Although Le Corbusier adopted Paris just a few years before he adopted his nom de plume and nom de guerre, Paris never really fully adopted him. For a half century, from 1915 – when he confided to his former employer Auguste Perret, “I feel equipped to prepare myself to realize my dream ... to live in Paris,”and spent two months researching French architecture and urban theory of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries under the cupolas of Henri Labrouste’s Bibliothèque Nationale (1854-75) – until his death in 1965, Le Corbusier would never lose his focus on the French capital.2 Even as he proposed plans for cities as diverse as Nemours, Algiers, Rio de Janeiro, and Bogotá, Paris remained a continual reference point: at once the main object of his desire to reform the city as inherited and the chief inspiration for his own history of urban theory and reform. He tested each step of his thinking against a large-scale vision for Paris, even if such projects – from the Plan Voisin of 1925 to sketches for a house for UNESCO in the 1950s – remained unofficial, exhibited and published widely, debated, but always on the margins of the mainstream discourse...