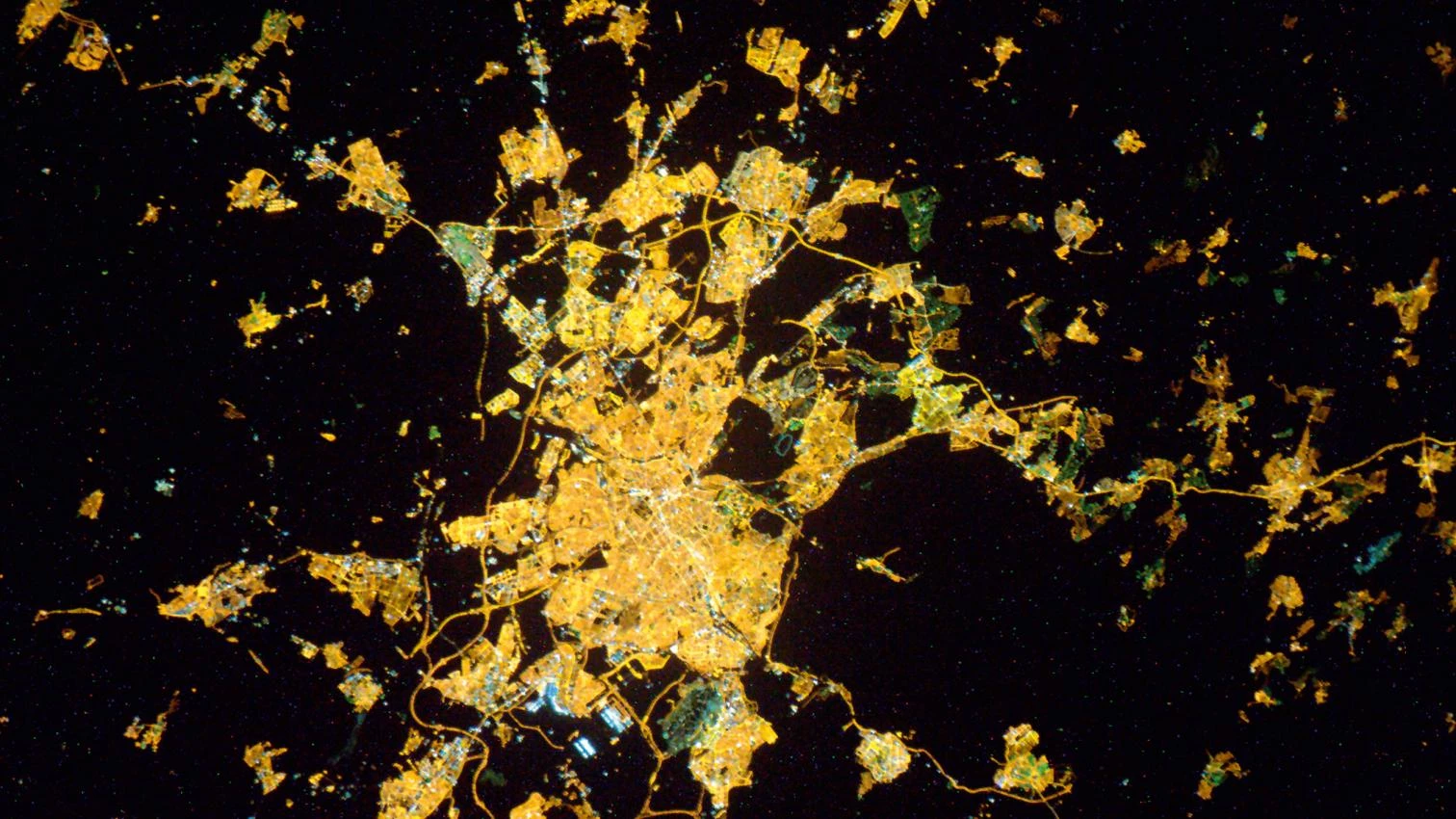

Madrid’s recovery is a bittersweet one. Ten years after the real estate bubble burst, the city is experiencing a vibrant growth, but the return of the cranes has not brought competitions back, and architects with a cultural dimension have had to turn to territories more generous with talent. The crisis of 2008 caused a devastating financial earthquake, driving many savings banks to ruin and forcing a bank bailout, and a social emergency with the rise of unemployment and evictions; but it also tore the professional tissue, shutting down countless architecture studios, and pushing the new generations of architects to emigrate. Today, the building boom gives reason to fear a new property bubble, and yet the landscape we find after the battle barely resembles the one we knew.

The shrinking number of competitions – due both to the lack of enthusiasm towards them from institutions like the capital’s city hall and to the drop of public investment in buildings – not only deprives architects of opportunities, but also robs cities of the chance to analyze their form. The large operations currently under way (Mahou-Calderón, by the M-30; Chamartín, extending the new train station; and Barajas, around the airport’s T4), are being developed in the absence of any professional or civic debate, entrusted to technicians from the administrations or to consulting companies, and with no discussion other than that of political parties on densities and uses, forgetting that what matters is the urban layout, which leaves a permanent trace on the land, defining its future.

Madrid is on the move, but architects move in search of opportunities abroad. Those who made a name for themselves during the golden years of social-opulence work hard to obtain international commissions, and those published here on American soil testify to this; some younger ones open offices outside Spain, and this issue also includes a couple of them; but most of the new architects use their versatile training to find room in collateral fields, or else are hired by big foreign firms. Those published here have all been trained at the 174-year-old Madrid School of Architecture, where the majority of them also teach, so their works in America offer transatlantic proof of the stimulating vitality of the city’s architectural culture: a culture sadly neglected by our political and economic powers.