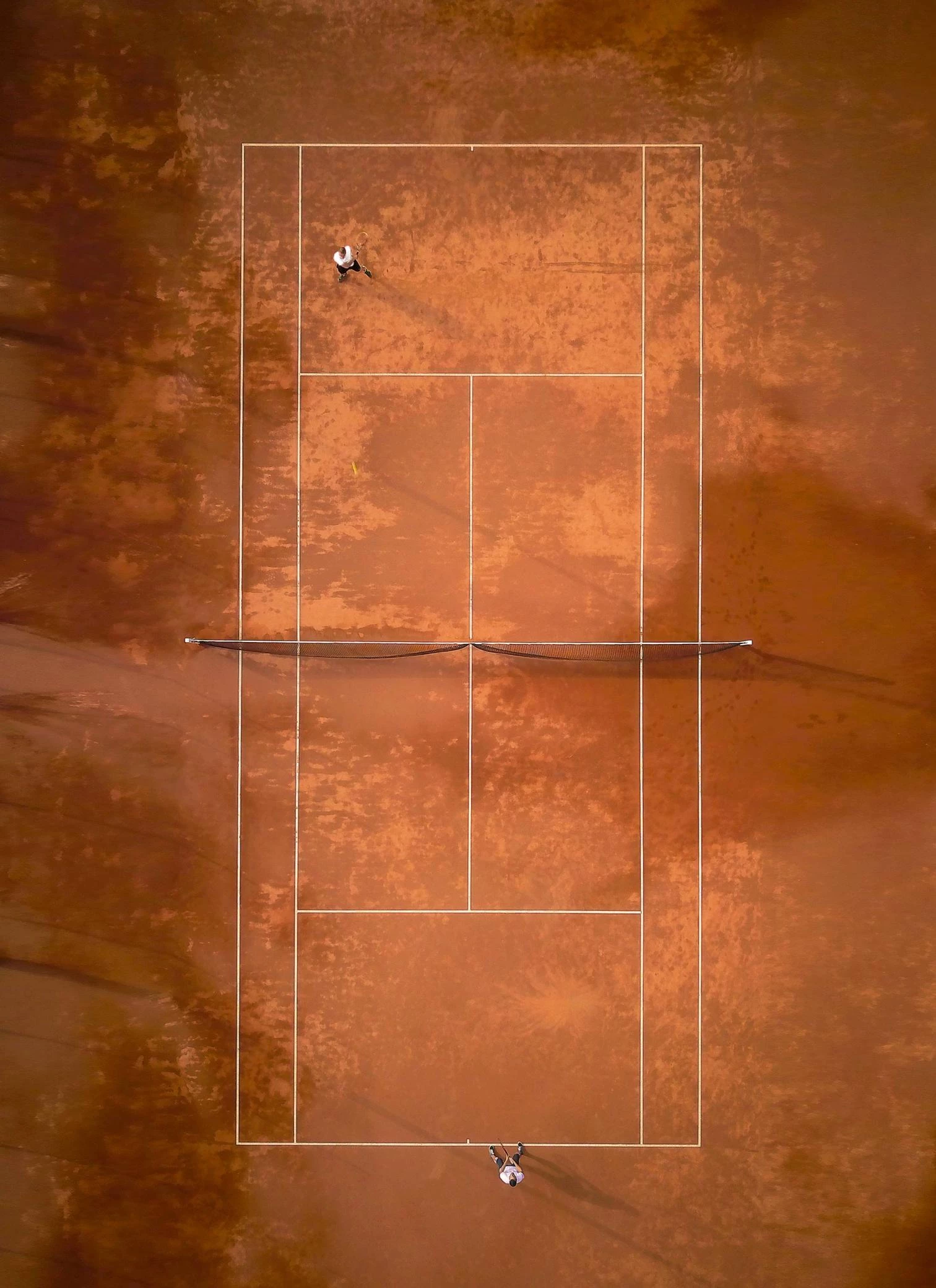

Play is something serious. The Neoplatonists used the oxymorons serio ludere and iocare serio to refer to a light way of dealing with matters of importance, in the Socratic tradition of seeking truth through dialogue. In the contemporary world, game theory has developed mathematical tools to understand decision-making in multiple fields, from economics to politics or military strategy, and the homo ludens described by Huizinga to underscore the social role of play has moved from elementary children’s games to the world of gaming, an industry that generates greater income than cinema and music together, and that extends today to the metaverse. Sport is nothing but a game transformed into spectacle, but similarly governed by rules and influenced by effort and chance. “All that I know most surely about morality and obligations I owe to football,” wrote Albert Camus, a praise of the formative virtues of sports that contrasts with the message of Woody Allen’s Match Point about the role of luck, in tennis or in life.

Time magazine releases an annual ranking of the 100 most influential people and of the 100 emerging leaders, and on the lists of 2022 there are only two Spaniards, Rafael Nadal on the first and Carlos Alcaraz on the second, two tennis players whose careers are built on talent and effort. If Nadal has won at Australia’s Open and Roland Garros the two trophies that extend his Grand Slam titles to 22 – the highest number ever for a male player –, and if Alcaraz has risen to the top post in the ATP rankings after winning the US Open, becoming the youngest No. 1 in history, the victories that justify their presence on the list are based on work rather than luck, and that turns them into role models in a country that remains reluctant to acknowledge and reward merit in the selection of its political and economic elites, too often co-opted through family, social, and ideological ties, which perhaps makes sport the last bastion of a meritocracy based on talent, training, and effort.

On the Time list are two architects, Francis Kéré and Maya Lin, as precocious in their careers as the tennis players – Kéré won the Aga Khan Award with a school built in his native Burkina Faso and designed in Berlin while still a student, and Lin was also in college when she won the competition for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington – and equally determined in the cultivation of talent through hard work, to become world figures: the first African to receive the Pritzker Prize, and the daughter of Chinese immigrants who is today an acclaimed artist and landscape architect. Did luck mark their early successes? Perhaps as it has in the case of the Mexican Frida Escobedo – the only architect on Time’s list of emerging leaders –, who after building the Serpentine Gallery pavilion has won the competition to enlarge New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, two ‘match points’ that predict a great career, but one which will have to be based on discipline and effort: those are the rules of the game.