The work of Alberto Campo Baeza pursues purity. Striving to be soul without body, he expresses ideas through geometry and light, stripping the building of its material nature so that it levitates weightlessly, free from its earthly prison. Oblivious to the tough constrictions of functional programs or constructive pragmatism, his architecture has a polished, pristine purity that we find published with ethereal images. In them one can glimpse at a world free of the turbulences of the century, protected and perfect in its crystallographic exactitude, spiritual and lyrical in its aerial substance, immaterial and luminous in its unseizable reality. Perfectly outlined and paradoxically blurred, this oeuvre becomes fixed in visual memory to render it immediately recognizable, through the colorless abstraction of its taut surfaces or through the translucent atmosphere of its prismatic volumes.

In the extreme purity of the form and in the aesthetic seduction of the image lies the pedagogical popularity of Campo Baeza, charismatic professor for almost fifty years at the Madrid School of Architecture, at first under the fatherly shadow of Javier Carvajal, and later from his own chair, made into a precinct of artistic elegance and cultural sensibility. Revered by his students, the architect returned this devotion with a priestly dedication to teaching, leaving a lasting impression on hundreds of youngsters, who would join the profession anointed with the holy oils of architecture as poetic calling. In contrast to other more prosaically sociological, politically militant, or eclectically disciplinary attitudes, the influence of Campo Baeza was built on the two pillars of purity and art, sparking the trivial reproach of having locked himself in an ivory tower.

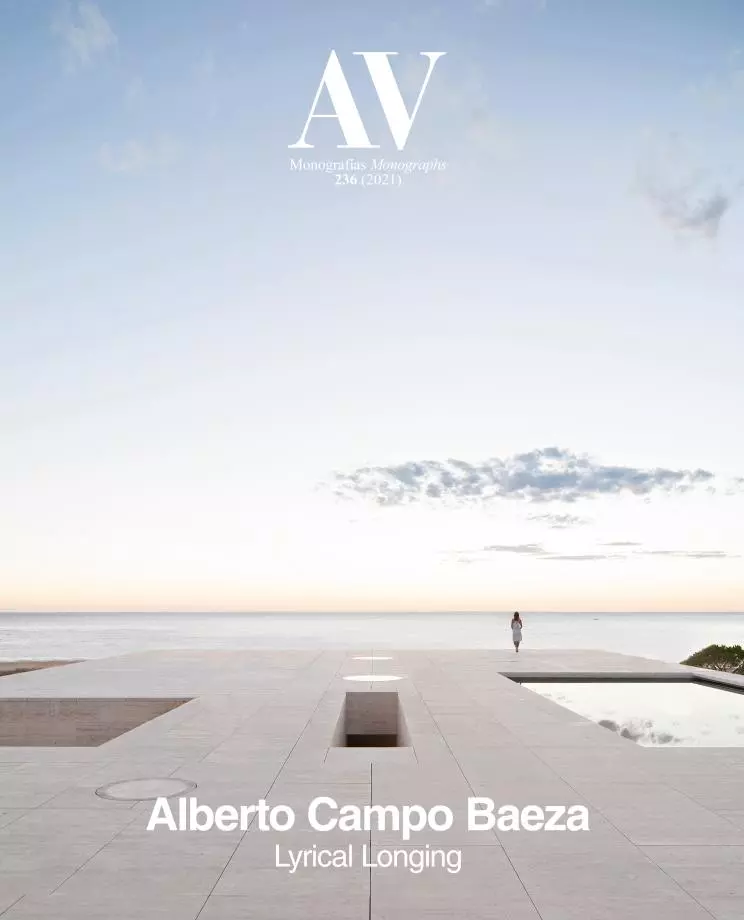

However, the angelical nature of the works does not preclude their contamination with a critical dimension that makes them witnesses of their time. The House of the Infinite, a laconic platform facing the Altantic, cannot be censored for lacking protection from the sun and wind, because its legitimacy lies in the portrayal of today’s subordination of the tactile to the visual; the Savings Bank of Granada, a prism of cyclopean structure, should not be assessed from the logic of an office building, because its monumentality reflects the symbolic protagonism of the local financial entities; and the Advisory Board of Castilla y León, a glass piece enclosed in a hermetic perimeter wall, does not deserve being mentioned for refusing to benefit from the views of the Cathedral, because there is no better representation of the endogamic isolation of current political elites. Polished purity can also be poignant.