“If your father had been named another way – Jan Pandovsky, for example – or if he had been a foreigner, maybe; but with a name like that, it’s no use.” With these words the historian Juan Pando Despierto was dismissed when, after the death of his father, he went to the bank to propose its hosting an exhibition of some of his photographs. Indeed the surname Pando lacked the glamour of those of his colleagues with foreign origins, such as Müller or Schommer, or of that of the Catalan Català-Roca. Or the lure of Kindel, the pseudonym invented – precisely for business purposes – by his fellow-Madrileño Joaquín del Palacio. This anecdote, told by Andrés Trapiello some years ago in the newspaper La Vanguardia (2 February 2001), in the context of the ‘discovery’ of Pando’s photos of the Spanish Civil War, introduces us to the bad luck of the personality and draws attention to the urgent need to rescue the figure of Juan Miguel Pando Barrero, whose birth centenary we celebrate this year, and give him the spot he deserves on the map of 20th-century Spanish photography.

In fact the exhibition ‘Photography: Light and Life,’ held in 1968 at headquarters of the afternoon newspaper Pueblo de Madrid – an extraordinary and subsequently ill-fated project of Rafael Aburto –, has been the only attempt to give a life devoted to photography a presence. In the field of architecture, Pando’s figure takes shape, for example, and significantly, in the fact that in the book Arquitectura Española Contemporánea, a basic historiography of our architectural modernity, published in 1961 by Carlos Flores, eighty photographs and sixteen projects are his. As many as thirteen images of his shoot of Molezun & Corrales’ famous Residencia in Miraflores de la Sierra appear high in the list of photographs, interspersed with sixteen, taken by Kindel, of the Caño Roto development of Vázquez de Castro and Íñiguez de Onzoño, and eight by Català-Roca of the Coderch y Valls house in Camprodón, It would be childish to try to rank the photographers who portrayed the corpus of Spanish architectural modernity, but in both quantitative and qualitative terms, Pando surely occupies a leading place. The close to 140,000 negatives included in the archives bequeathed to Spain’s Institute of Cultural Heritage speak of the sheer magnitude of a career that is only now beginning to be documented and examined, thanks, among other things, to the research project ‘Photography and Modern Architecture in Spain, 1925-1954.’

Less well-known than the work of Català-Roca, Schommer, or Kindel, but not inferior to them in quality, Juan Pando’s legacy includes 140,000 negatives that have only recently begun to be studied systematically.

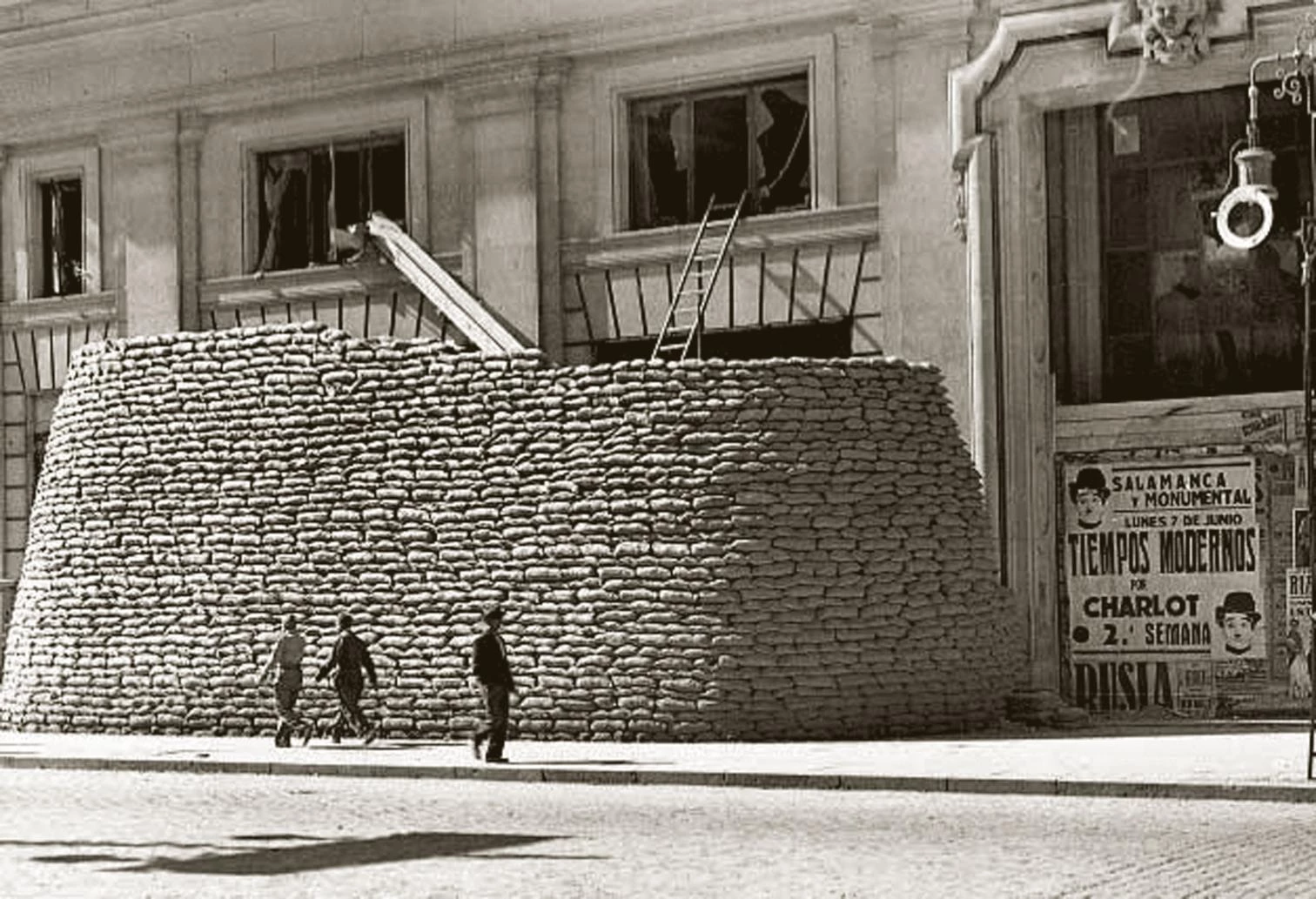

Juan Pando was personally introduced to architectural photography through the commissions given him, beginning in 1948, by the construction company Agroman, his main client throughout his professional career, and for almost a decade starting in 1950, by the General Directorate of Devastated Regions. Pando had seen firsthand and portrayed not only the architectural devastation, but especially the intensity of the human drama experienced in his native Madrid during the war. Fifth child of a typographer, at barely sixteen years of age he began to learn the photographic craft, developing prints of monumental heritage in Mariano Moreno’s well-known art reproductions shop. A friend of the pictorialist José Ortiz-Echagüe, Pando immediately launched a personal practice that was close to the documenting of customs and manners. So it was that after five years of field work and dark rooms, the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War found him in the capital already ‘trained’ and capable, as a photojournalist despite his youth, of making visual reports with a clean, clear, and beautifully unbiased view of human relations taking place amongst debris and barricades in a besieged city and in trenches on the battlefronts, which he himself was sent to. As in architecture of the postwar, his surname could not compete in terms of critical acclaim with those of his contemporaries at home or abroad, from Capa to Centelles, but his snapshots – taken with a bulky second-hand Speek Graflex – soon began to appear in the newspapers ABC, Ahora, and La Voz, and drew the attention of the agency Associated Press, which hired him for the four years that the war lasted.

A Clear Gaze

Despite this success, his personal experience made it hard for him to abstract himself from the drama (his brother Luis fell and disappeared in the Segovia front) and the photographer gave up journalism altogether, internally and externally silencing and obscuring all that he had experienced and photographed during those years. He founded the Foto-Pando Graphic Information Agency (1940-46) and distributed shoots of World War II. Later, in his studio in the heart of Madrid, on Calle Augusto Figueroa, and up to his retirement in 1983, with the collaboration of his only son during the final decade, he devoted himself to industrial and advertising photography as well as to photographing architecture and public works, for the purpose traveling extensively through the Iberian Peninsula and Morocco. Working for Devastated Regions, Agroman, the Construction and Cement Institute, Dragados y Construcciones, the Directorate-General of Architecture, Madrid’s General Office for Urban Planning, and so on, Pando became an ‘ex officio’ photographer in the very best sense, neither necessarily nor exclusively in architecture. He was a rigorous professional in possession of excellent technical resources for Spain of that time – for these jobs he worked with large machines like the Graflex Speed Graphic or the Linhof Technika, which allowed optical correction of perspectives – and capable of meeting the expectations of clients with respect and pulchritude, whether they were public organisms, corporations, or architects.

Having begun his career as a documentalist during the Spanish Civil War, Juan Pando became an ‘ex officio’ photographer capable of portraying buildings with a nakedness not lacking in poetic quality.

The mentioned friendship with Carlos Flores earned him the trust of architects, who soon saw their works published in the leading magazines of the period, both in Spain and abroad, including L’Architecture ‘dAujourd’hui. The likes of Luis Gutiérrez Soto, Miguel Fisac, Julio Cano Lasso, Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza, Rafael de La-Hoz, and Juan Daniel Fullaondo relied on his services, making him the Madrid version of Català-Roca, the photographer who with Maspons/Ubiña documented most of the work of Catalan architects. But in continuity and quality, those who repeatedly – if not exclusively – hired Pando to document their architectural works were Rafael de la Joya and Manuel Barbero, César Ortiz-Echagüe and Rafael Echaide, and Fernando Moreno Barberá. The nature and context of these works, besides compatibility of personaliy between Pando and the different architects, clearly explains the mutual faith and trust.

“Without underrating what we call ‘artistic’ photography, I am convinced that there is only one kind of architectural photography, that which conveys the architect’s idea.” These statements of Ezra Stoller, born the same year as Pando, point to a simple synthesis of critical categorization. Kindel rode through the purified abstract aesthetic of his images, Català-Roca intoned an extreme compositional, productive, and technical virtuosity, and Paco Gómez perfected the poetic lyricism of the visual narrative. Contrary to these plausible practices and accents of his more illustrious colleagues in the trade, Juan Pando presented nothing, in Carlos Flores’s words, but “an earnest, calm, and clear gaze”: photographer of snapshots, he took sequential photos that presented architecture with a natural realism – with the nakedness condensed by his negatives – that the amplifier hardly masked. His photographs of architecture combine documental aseptic description – reinforced by an extraordinary mastery of the technique – with the life-giving, evocative, non-dramatized presence of the user of architectural and urban space. If such a synthesis is art, then so be it. Precisely, Juan Pando’s art consists in making what is difficult look easy: condensing in images, as in the war, the small and great battles that gave rise, happily, to our architectural modernity.