Houses of Muses

Four Museums on Four Continents

Herzog & de Meuron, Museum Küppersmühle Extension, Duisburg (Germany)

Ptolemy, the Greek pharaoh of Egypt, ordered the building of the Mouseion of Alexandria in the year 280 BC, and in doing this, what he was inventing was not so much a place where erudites could come to study under the sponsorship of the State, but rather a concept and a name that would ultimately thrive in Western culture.

As a fruit specifically of Hellenistic civilization, museums altogether disappeared for centuries, to reappear when the autumn of the Middle Ages revived them in part, but transformed into chambers where the nobility kept an assortment of objects ranging from marble crucifixes to bezoar stones by way of unicorn horns. The Renaissance then resuscitated the name, Latinizing the word to museum, and initiated and promoted the act of collecting, this time less interested in rarities than in the strictly artistic, which would eventually flourish in the galleries of palaces during the Baroque period and the Enlightenment, before the revolutionary Zeitgeist ripped museums of their aristocratic nature and turned them into the bourgeois institutions they remain today.

Proof that museums are bourgeois inventions is the fact that the modern capitals of the world have since the 19th century aspired to have specimens of them by the dozens, to the point of making them no less than symbols of democracy and knowledge. Deeply rooted in our values, this symbolic tradition explains how – even in our digital societies of today, where knowledge has ceased to have the aura of yore – museums as institutions have not lost an iota of their prestige, albeit perhaps a stature based on a utility that, on the other hand, is balanced out by their inflated role as urban icons and catalysts, as demonstrated by the famous ‘Guggenheim effect.’

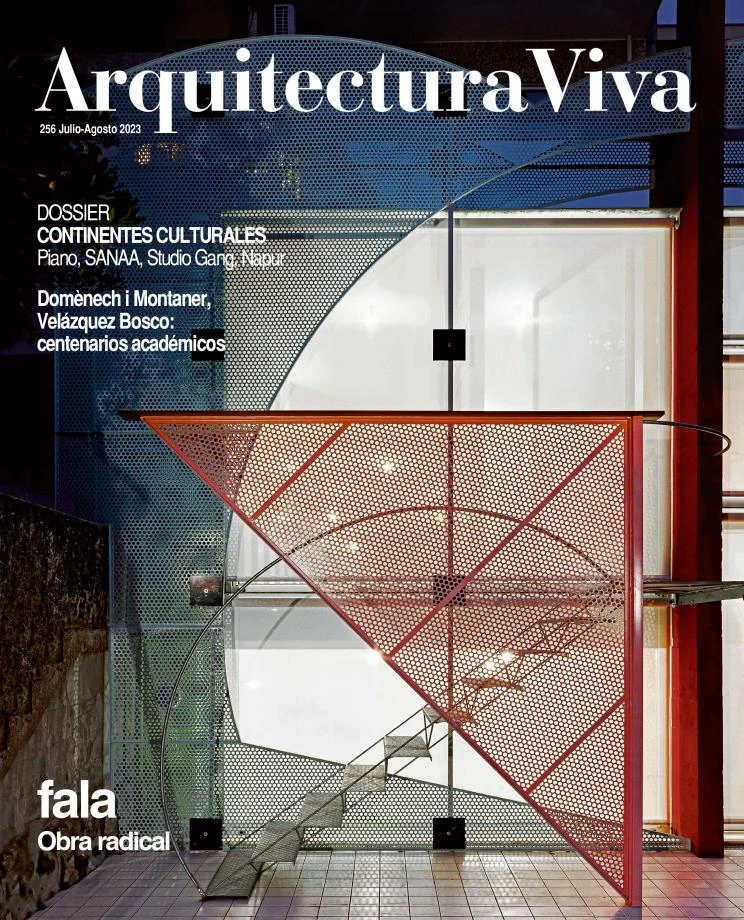

Arquitectura Viva in this issue takes stock of the mutations that museums as architectural objects have undergone, through a dossier that presents four recently completed examples spread out around the globalized world. Renzo Piano Building Workshop’s Istanbul Museum of Modern Art, situated on the banks of the Bosphorus Strait, echoes the industrial past of the location while oozing civic optimism through the transparency and fluidity of the constructions. Sydney Modern, SANAA’s extension of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, presents different pavilions interconnected with roofs and respects the greenery of the surroundings. Studio Gang’s Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City engages with its exhibits by means of peculiar organic geometries. And Napur Architect’s Museum of Ethnography in Budapest lays out the program under a large and gently curving green roof that doubles as a public outdoor lounge.

Tadao Ando, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (USA)