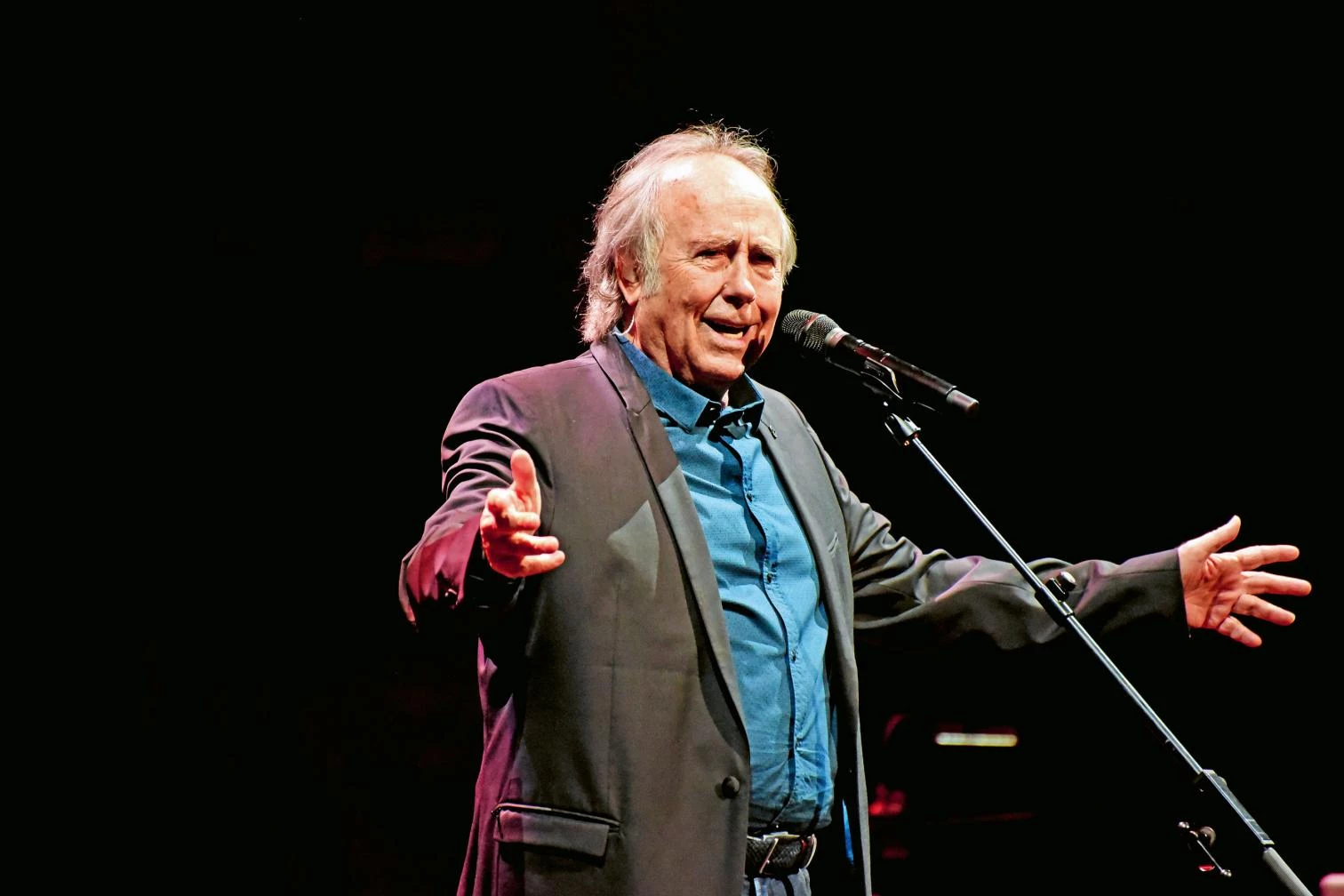

As good fortune and the grace of friends would have it, I found myself amid a festive crowd of Joan Manuel Serrat enthusiasts during a recent visit to Madrid. Unexpectedly, there I was on a wonderful seat, a longtime admirer of the poet and musician from Poble-sec who, for almost six decades, has brightened the longings, experiences, and tribulations of us all. Waves of emotion swayed the thousands gathered at the celebratory evening in the Palacio de Deportes. Cheers capped Serrat’s farewell concert in Madrid, a city that has welcomed him with open arms and a heart as impassioned and large as the entire Iberian Peninsula. After singing an energetic rendition of Fiesta, Serrat humbly waved goodbye to an all-standing audience, turned around, and left the stage. Just as the velvet curtain was about to close, he looked back and sent a wink like a flash of lightning. I remembered Leonard Cohen’s remarks at his last press conference. He assured everyone with a similar wink on his eye that there was no such thing as a last act. He intended to live forever.

And so it will be for Serrat, whose catalog of songs has sustained three generations and will sustain many more to come. How could it not be when his timeless compositions astonish with their tender and essential architecture? Compositions that harbor the fluctuations of every heart as each one builds its own singular destiny. Take Paraules d’amor (1969), in which Serrat harnesses the travails of adolescent love to sublime reminiscence. Or the consummate Romance de Curro el Palmo (1974), beautifully sung on this occasion, a song that I have admired since I first heard its enthralling opening: “La vida y la muerte / bordada en la boca / tenía Merceditas / la del guardarropa…” A song that startles with its lyrical economy as it weaves a line-up of personajes to reveal an exquisitely composed, redeeming story. (The late Antonio Vega transported this song to another height with his unrivaled 1995 rendition.)

Ah but there are so many other indelible Serrat songs: Penélope, Por las paredes, La paloma, Canción última, Pueblo blanco, De cartón piedra, Lucía, Del pasado efímero, Tío Alberto, Pare, Piel de manzana… and that ageless construction, Mediterráneo (1971).

I remember, on first hearing it, how it instantly transformed the enormous Pacific Ocean of my Costa Rican childhood into an intimate sea, a sea whose waves spelled a retinue of commonalities. Here lies the magic of Serrat: how he shapes a song or poem to make it familiar and moving in its universal sweep. When Serrat released the transcendent album Miguel Hernández (1972), the entire Ibero-American world trembled with the contagious ardor of freedom. Serrat unleashed the earthy force of the poet from Orihuela to remind us that all the miserable prisons that incarcerated him could never suppress or silence him. For like Hernández, Serrat understands that love and freedom are life’s immortal wings, soaring and sliding down as in the resplendent poem ‘La boca’ (Mouth): “El labio de arriba el cielo / y la tierra el otro labio” (“The upper lip, sky, / the lower lip, earth”).

A thousand and one more thanks, Joan Manuel.