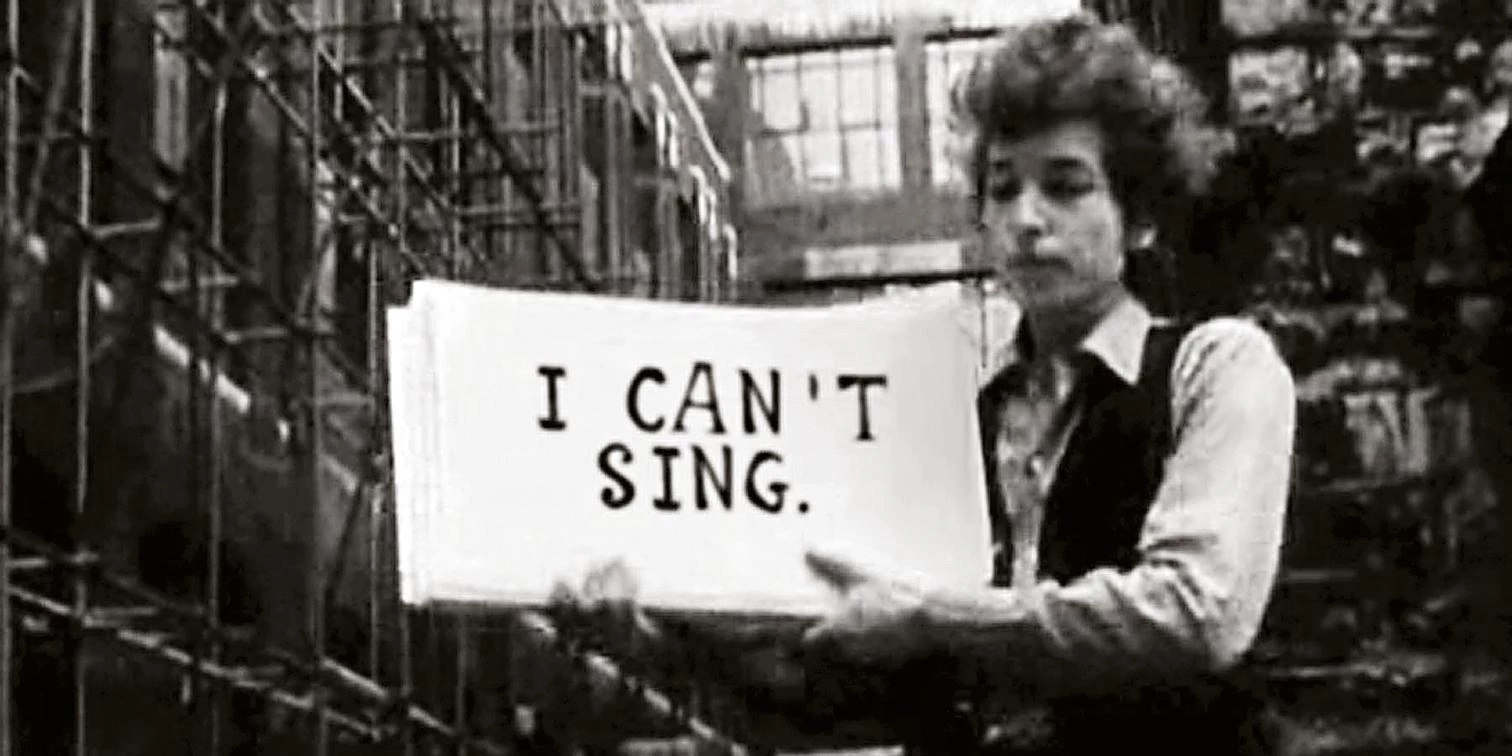

Subterranean Homesick Blues (1965)

When Peter Zumthor received the Pritzker Prize in 2009 in Buenos Aires, the United States ambassador to Argentina gave a reception in his honor. In the midst of the customary toasts, Zumthor thanked the ambassador and ended his remarks by commenting that it felt good to be congratulated by a country whose last great cultural contribution to the world had been Bob Dylan. Zumthor obviously intended a not too subtle rebuke to the representative of a country that, at the time, was deeply embroiled in the ill-fated war in Iraq.

It would have been hard to disagree with Mr. Zumthor, certainly not today with the news that Bob Dylan has been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for 2016. For the many who have followed the unwavering, unpredictable arc of the artist from Hibbing, Minnesota, spanning more than five decades, the news is both long overdue and timely. It arrives as the United States, engulfed in a new tempest of contradictions, battles to re-program its inner compass through a fraught and protracted presidential election campaign. It is a testament to Dylan’s relevance as an artist that his writings remain as unshakable today as the day when they were written. Just as we return to the works of Homer, Shakespeare, Rimbaud, or Vallejo, poets who documented the foibles and aspirations of their times, so Dylan’s epic trajectory has pierced American culture with its diamond-sharp consciousness, integrity and vision. He is a consummate performer in the broadest meaning of the word, an artist whose significance transcends the vicissitudes of music to spell out a legacy of staggering lyrical power. Dylan traverses past, present, and future histories to unfold a turbulent yet moving story called America, the ongoing version of an elusive yet ever-promoted Promised Land.

Take for instance one of Dylan’s most extraordinary songs, Blind Willie McTell, recorded in 1983. A song that the songwriter decided at the last minute not to release. It is a song that, beyond its perfect tonality and rich texture, is sublime, as are John Brown, Visions of Johanna, Seven Curses, Workingman’s Blues #2, Foot of Pride, and Love Minus Zero / No limit, songs that I frequently use in a seminar where, verse by verse, I teach students the intricate structure binding the construction of these songs. For Dylan is foremost a master builder who constructs through images a spatial realm measured not only by layers of time but also by involving all the senses in the experience of his work. The delicate yet brutal landscape that Blind Willie McTell delineates for us is a world where we see what the blind bluesman cannot see, yet is able to transform, transfigure, and reveal through his luminous omniscient touch. The song is devastating in its delivery, tactility, and poetic urgency as Dylan takes us through an unsettling yet sensual travelogue that reveals that all is not well in the land of the free in its pursuit of happiness.

When President Barack Obama awarded Dylan the Medal of Freedom in 2012 (coincidentally Toni Morrison, the last American to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1993, was also a medal recipient), he observed that “there is not a bigger giant in the history of American music; all these years later he is still chasing that sound, still searching for a little bit of truth.” Can there be a greater compliment for any artist, who in his or her own way searches “for a little bit of truth,” not the “easy comes/easy goes”, or the monolithic or imperious version of truth, but the truth found day-by-day, lyric-by-lyric, within the wonder of art and its inextinguishable pulse? Congratulations, Mr. Dylan!