Every avant-garde recognizes itself in modernity, but not all modernity recognizes itself in avant-gardes: thus starts an ‘aesthetic essay’ that explains the complex, often contradictory tenets that gave rise to artistic modernity. ‘Aesthetic essay’ in quotes because, though the author acknowledges that his tone and liberties compel him to say ‘essay’ instead of ‘history,’ the book lacks the banality we now associate with the essay genre, and has all the conceptual density he is known for, plus his method of combining fragments to create new discourses: the method Lévi-Strauss called bricolage, and which Schiller described as “hermaphroditism of knowledge.” Other than as bricoleur, Simón Marchán Fiz plays the archaeologist digging up modern roots, binding texts written over decades and picking up the thread of a previous book in a way that while it presented the transformation that allowed going from classicist commonplaces to perspectives of Romanticism, the new tome tackles the dissolution of the romantic paradigm. A dissolution that affected ‘substantiality,’ the idea that art could be sustained by stable, transcendental principles.

Marchán shows that the blowup of the ephemeral romantic framework can be seen as a double twist to ‘accidentality.’ On one hand to external accidentality, which no longer looks for a spiritual figure in natural or artificial objects, but a mere apparition of the ephemeral, of all Baudelaire associated with “beauty of the present.” On the other hand to internal accidentality, focused on those psychologistic and primitivistic accents that art began to experience in the mid-19th century.

With literary skill the author addresses the accidentality theme mostly in the book’s first part, where he presents some ‘great moments’ of the making of modern art: from the Realism of Courbet and Baudelaire to the emergence of Cubism and its phenemenological components, Futurism and dynamic perception, or Symbolism in its double aspect of return to both psyche and primitive.

These transformations – which bore upon something as fundamental to art as the idea of ‘representation’ – were a baby step in the abstract revolution Marchán deals with via the construction of the ‘principle of abstraction,’ through analogies of painting with music or literature, but also the search for art’s ‘degree zero,’ which defined pioneers like Kandinsky; or the construction of the ‘enhanced abstraction’ that modern architecture was.

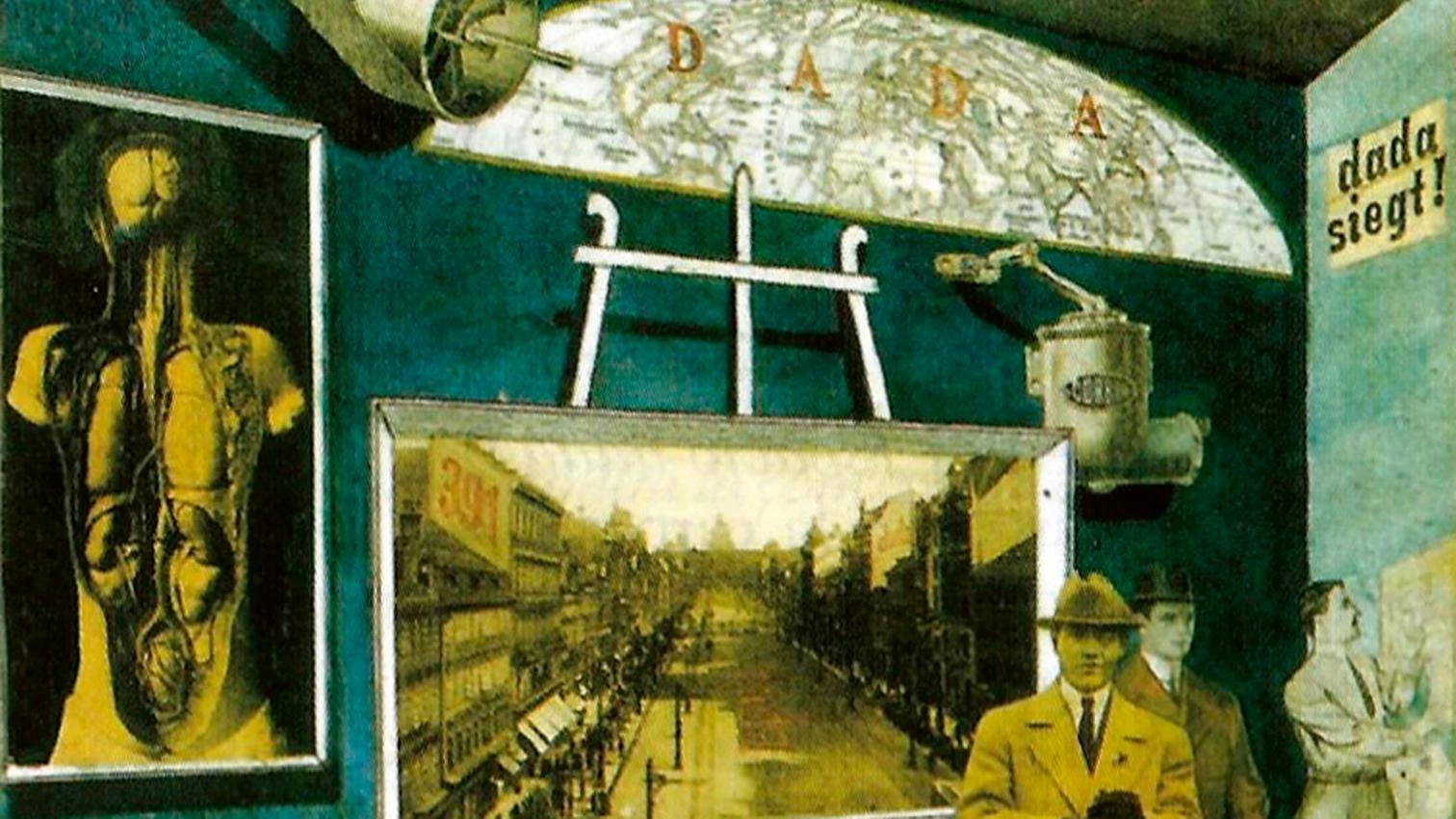

The book ends with the final and most radical modern twist, the conceptual, through which art tried to shed artistry and with huge ambition appropriate everyday life. A twist presented through a selection covering predictable themes like Dadaism and Constructivism, but also less known subjects like the aesthetics of waste in the Merzkunst of Schwitters.

In this at once canonical and personal way, Marchán delivers a kaleidoscope reminding us that modern works have yet to outdo modern ideas, and that they have left us with utopian surpluses still to be updated.