The Oil of Icons

The annual Arco fair shows the incestuous relationship between art and architecture, in times of sound and fury ruled by spectacle, celebrity, the media and commerce.

Between fitur and sicur, coinciding with International Fashion Week, ARCO celebrates its 25th anniversary. The fairs preceding and following the art fair at IFEMA serve to mark its boundaries. The International Tourism Fair describes the consumerization of geography, referring to art as entertainment and as an itinerant engine of leisure deranged by a symbolic bulimia, while the International Security Fair delimits the topography of fear, tying up with art as a postmodern religion and a source of the timeless and the sacred that protects us against contemporary transience and un-certainty. The tourism of art feeds on its fungible luxury, the security of art comes from its spiritual nature, and both – consumable distinction and immaterial protection – find hypostatic union in fashion, something that is at once fleeting and eternal, material and intangible, and the coinciding Inter-national Fashion Fair and Pasarela Cibeles shield ARCO so that no one can say that art is naked, while the Casa Pasarela extends the world of style to the cluttered realm of home décor, protective dress and intimate scene of the rites of collecting, which trans-forms the objects of art into the gods of the home. IFEMA thinks for us.

Twenty-five years after the Guernica’s return, ARCO turns a quarter-century by inviting a country that commemorates the 250th birthday of its star genius. Such an accumulation of anniversaries invites one to contemplate this motley fair in the at once dazzling and dolorous light of another citizen of felix Austria, the late Thomas Bernhard, who made his country and art the main targets of his critical pessimism. It is not easy to imagine the author of The Loser looking for traces of exceptional talent in this busy bazaar’s pandemonium of ideological and formal offers, nor is it possible to transfer the thoughtful contemplation of the main character of Old Masters to this carnival of modern masters and postmodern epigones, but only a gaze as caustic as Bernhardt’s could do justice to the colossal, consoling, and consensual fiction of contemporary art, where “the suspension of disbelief”– in a man-ner ironically more literal than in literary fiction –is the only iron rule written on stone on the door that leads into the fair.

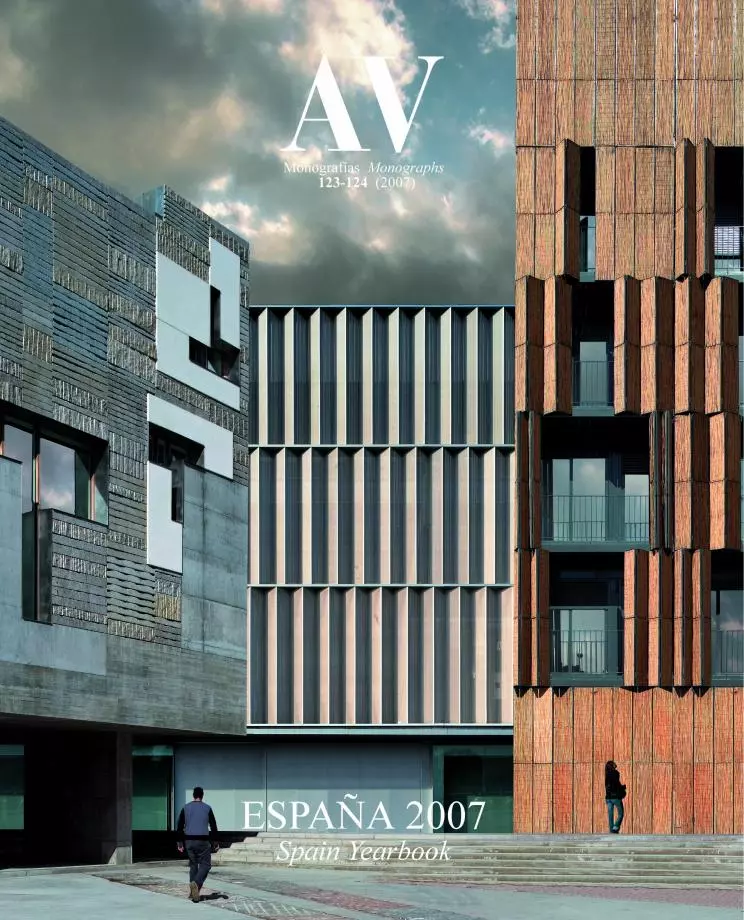

The newspaper El País has entrusted the design of its stand to an artist-architect, Juan Navarro Baldeweg, and this fortunate choice serves to illustrate the close contemporary ties that exist between two sister disciplines which the strictest form of modernity tried to keep hygienically separated, but which even then engaged in incestuous cross-fertilization, spawning fruits that were often healthy but every now and then freakish. The less fortunate results of this self-withdrawn in-breeding comes from confusing architecture and sculpture: a confusion that an exhibition titled “ArquiEscultura” equivocally plays with at the Guggenheim-Bilbao, a singularly appropriate venue for the presentation of such a phenomenon considering that Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim has been for the current gen-eration what Wright’s New York Guggenheim or Utzon’s Sydney Opera House was for the previous ones. Paradoxically, this sculptural architecture has been pushed to the limbo of midcult by the same people who put it on top, and today the Californian shares with our very own Santiago Calatrava that vague space which – with the permission of Joseph Ratzinger and the International Theological Commission – is inhabited by those who, un-worthy of the paradise of criticism, neither deserve the tortures of hell, and whose popular success makes a forced stay in purgatory unlikely.

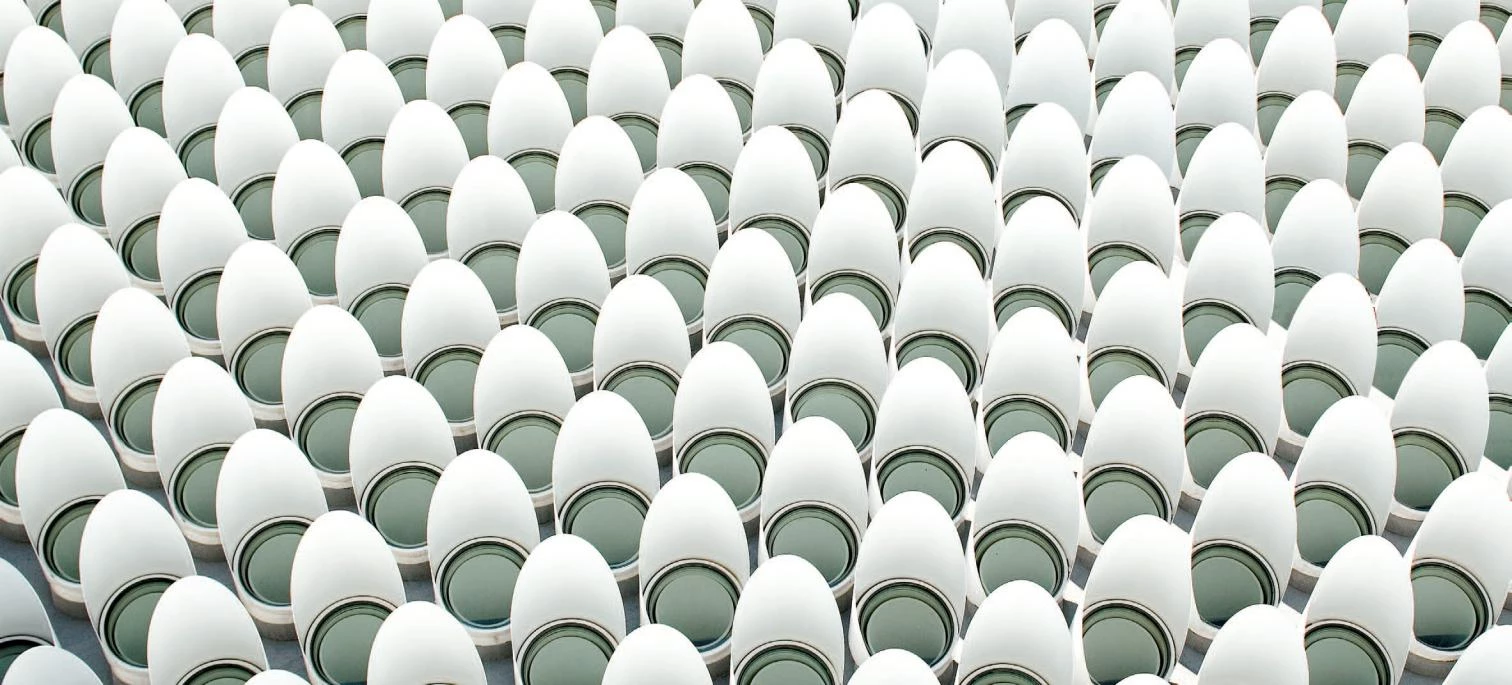

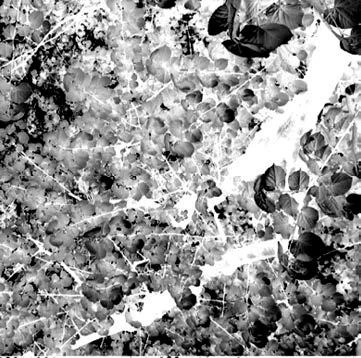

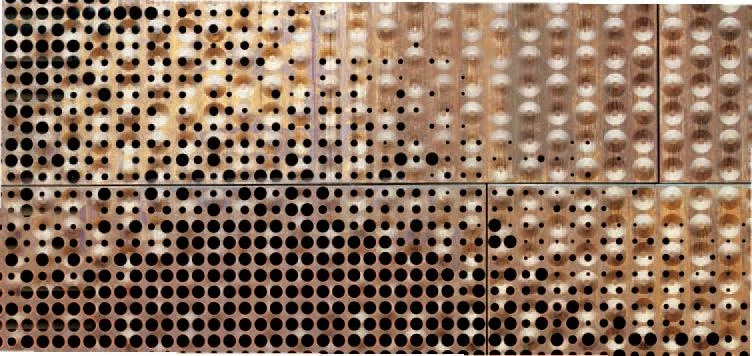

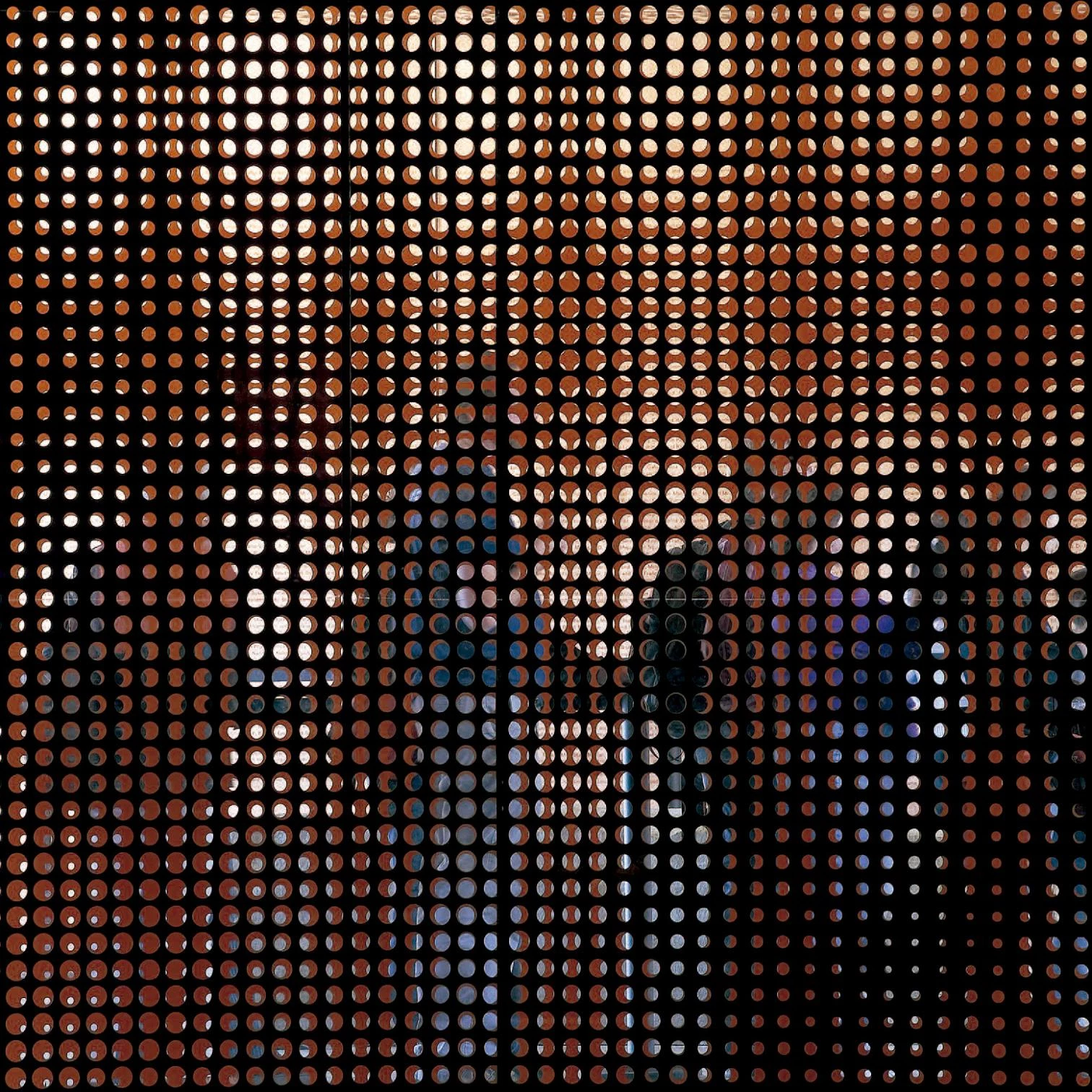

The Basel partners Herzog & de Meuron have served as inspiration for the art world through their devoted exploration of matter, evident in the textures of facades or the interiors of their de Young Museum in San Francisco.

In the limbo of opinion and the heaven of the masses, these artist-architects perfectly illustrate the diluting nature of celebrity. Frank Gehry is the star of a documentary filmed by Sydney Pollack, and as apprentice in his studio he has taken in some-one like Brad Pitt, who, incidentally, has by now opened his own design office and will for a start be decorating the hotel he is building in Las Vegas with George Clooney. But Gehry’s work is sliding down the mannerist slope of the repeated stroke – “sometimes I feel like a serial killer,” he has joked, “stop me before I do it again.” Santiago Calatrava, in turn, was the architect most flattered by the American media after his project for Ground Zero, and he is at this very moment the first architect since Breuer, back in 1972, to be exhibiting his work in New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, to boot between Fra Angelico and Van Gogh, making true what we had judged as megalomaniac aspirations to compare with Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo. But this astronomical rise of his naïf watercolors has been added to the futuristic kitsch of his latest constructions to provoke a rough tide of hostility in Anglo-Saxon criticism, which has censured him without mercy.

The magazine Art Review has published a list of 100 people it considers most influential in the art world. Neither Gehry nor Calatrava makes it there, but the list includes four architects whose names and mutations of the past year mark the trends emerging in the world’s fair of vanities or taste. Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid – Pritzker Prize winners in 2000 and 2004, respectively, and formerly master and disciple in the London crucible that the Architectural Association is – made number 14 and number 20 in the previous list, but now drop to 49 and 75. In the first case it is perhaps illustrative of general disappointment at how the Dutch architect has moved from the diagrammatic projects and political-ideological collaborations in Documenta exhibitions to the conventionally sculptural and popularly successful works that followed his keen interest in the so-called “Bilbao effect.” In the other case it is perhaps also a sign of general exhaustion with the Anglo-Iraqi’s worldwide implantations of fluid forms, multiplied to infinity by the snowball fame of the “Casta Diva”.

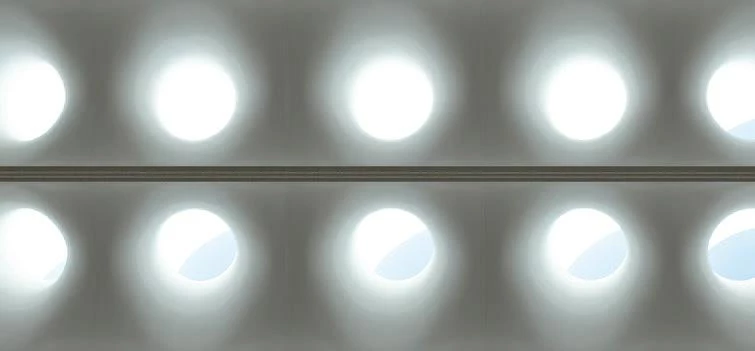

The Italian Renzo Piano has become the favorite of art institutions, which admire the sober elegance of his works, shown in the luminous spaces beneath the exact landscape of skylights in his recent High Museum of Atlanta.

In contrast, Herzog & de Meuron and Renzo Piano, Pritzker winners in 2001 and 1998 who did not make the previous list, are now in it and quite high up, as numbers 11 and 35. In one case it may be evidence of fascination with the relentless material and formal explorations of the Basel partners, a verification of their solid ties to the art scene, which often include collaborations with prominent members of it, and admiration for their museum projects, most recently the New de Young Museum in San Francisco, a piece of exquisite make with copper cladding perforated with the lights and shadows of the greenery, one that in time will dis-solve in the park it is located in. In the other case it could be acknowledgment of the impeccable efficiency and exact elegance of the Genoese master, no doubt the most coveted in the demanding universe of patrons, artists, and curators who value as frames for art the refined and luminous silence of his works, effortlessly proven in the most recent of them, the extension of the High Museum in Atlanta, a series of immaculate volumes clad in white aluminum and crowned with a tight forest of skylights rendered with his cool material inventiveness

After this concert of duets, a distracted walk through the ARCO pavilions can suggest that the essential works of our times exist outside this mobile, portable fair, a mix of the commercial center and the academic salon of conventional reputation. Whether because we do not know where the spirit blows, or because the scale of the works overflows this ephemeral city of plaster and celebrities, beyond the metal architectures, perforated volcanoes, or fields of concrete stele, ARCO is a plateau for a motley audience, solitude inhabited by multitudes, where every celebrity has a spotlight, just as every icon in the stifling penumbra of an orthodox church has an oil lamp burning before it. In a Bolshevik story, the main character is a revolutionary who, at one point, in a crossed gesture of provocative pragmatism and challenging respect, uses the icon’s oil to grease his boots. Perhaps the dazzle of ARCO de-serves the same treatment as Byzantine oil lamps, and maybe we ought to walk through its labyrinths with the spirit of the unbeliever before a sacred image, concerned only with finding the best grease for the cracked leather of our shoes, totally unconcerned with the “art-fitur” of consumerism and the “art-sicur” of protection, and distractedly ignoring the insinuations of the “art-catwalk”.