A symbol of modern tragedies, Guernica turns 80 years old, and to celebrate this, the Reina Sofía Museum has inaugurated a major exhibition titled ‘Pity and Terror: Picasso’s Path to Guernica.’ It has also been twenty-five years since the mural-sized canvas arrived in Madrid, after an odyssey of half a century; wanderings which, beyond the museum’s tribute and all the tags that the painting’s powerful symbolism can give rise to, invite alternative readings, among them Guernica’s relationship with architecture.

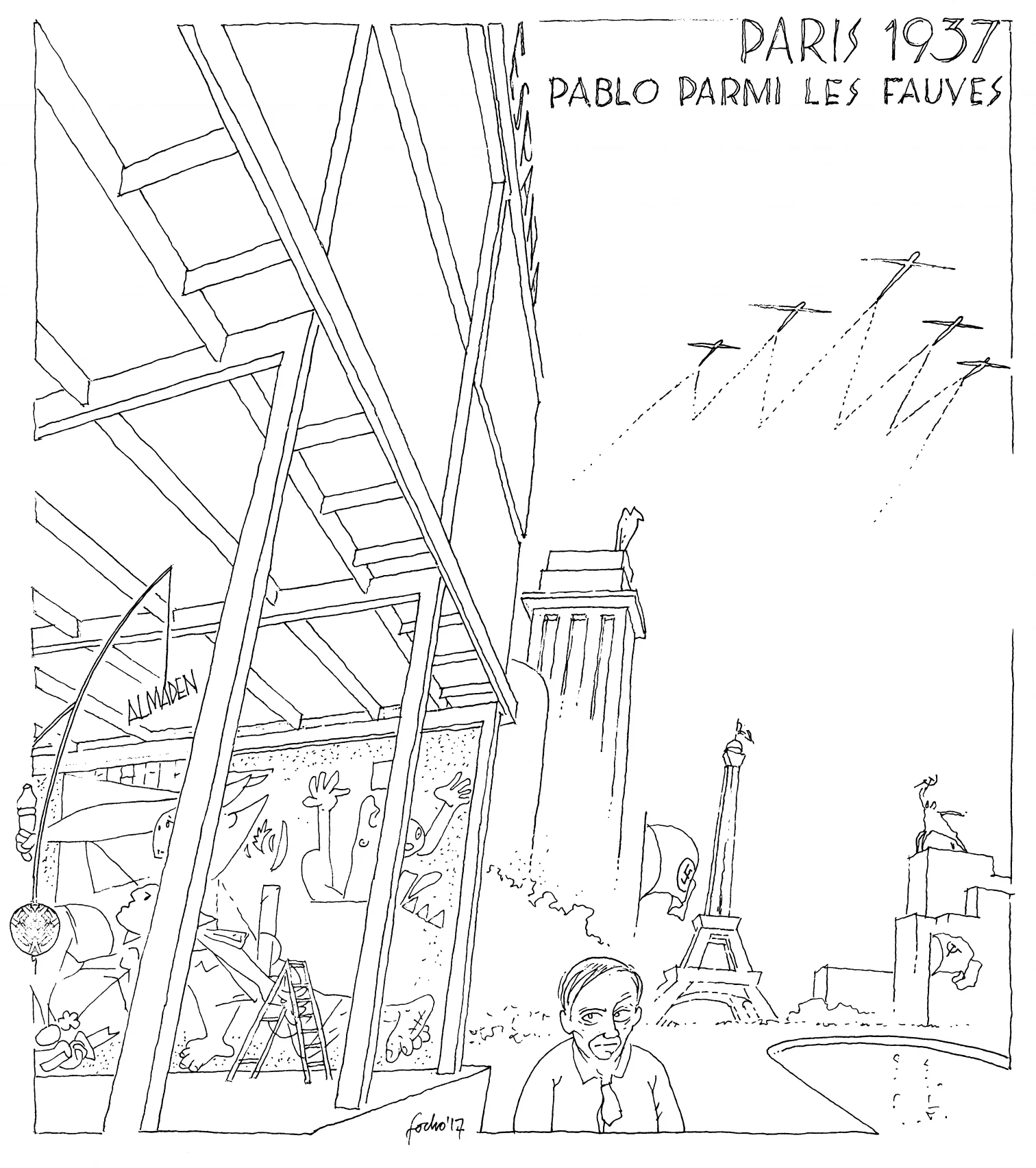

Commissioned to Picasso by the government of the Second Republic, Guernica – with other works speaking out for the republican cause during the Spanish Civil War, such as Josep Renau’s photomurals or Alberto Sánchez’s soft obelisk – was conceived to be the main attraction in the Spain Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair, by architect José Luis Sert. When the fair ended, the painting was returned to Picasso, who kept it in his Parisian atelier until 1941, when the Nazis marched in, at which point he decided to entrust it to the MoMA of New York, for safekeeping there until the reestablishment of democracy in Spain. In 1982 it came home to Madrid, to be displayed first at the Casón del Buen Retiro, beside the Prado, in an urn-shaped vitrine designed by José María García de Paredes, and eventually where it is now, in a white room in the Reina Sofía. From the propagandistic pavilion to the white box, passing through the Zeitgeist vitrine, the various homes of Guernica suggest the different ways this strongly cathartic work of circumstances has been interpreted.