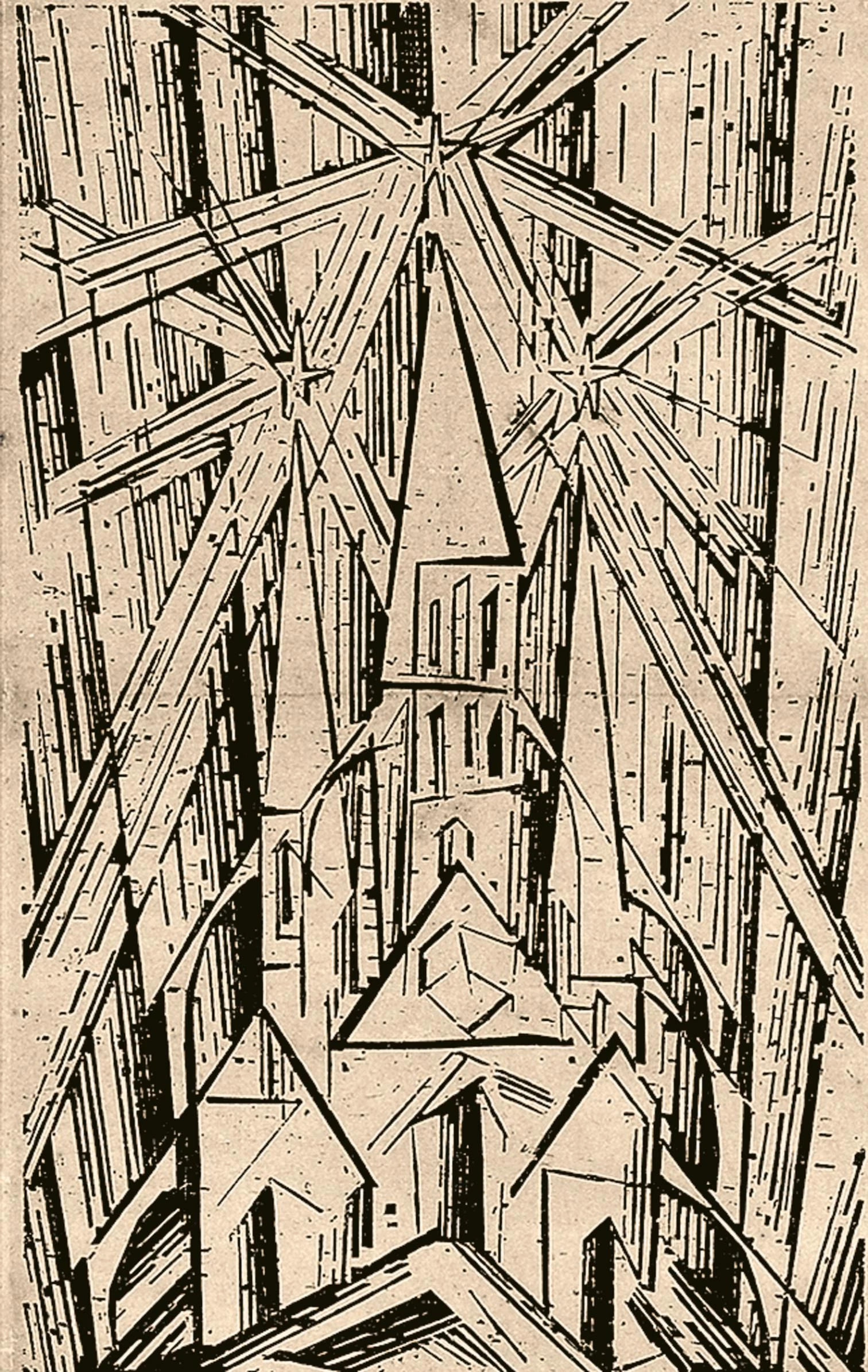

The history of the Bauhaus has partly been that of a misunderstanding, at least for the general public, which perhaps owing to bestsellers like Tom Wolfe’s From Bauhaus to Our House, has tended to see the school that opened its doors in Weimar a century ago as the quintessential representation of the modern ‘style’ of white buildings and exquisite chrome furniture.

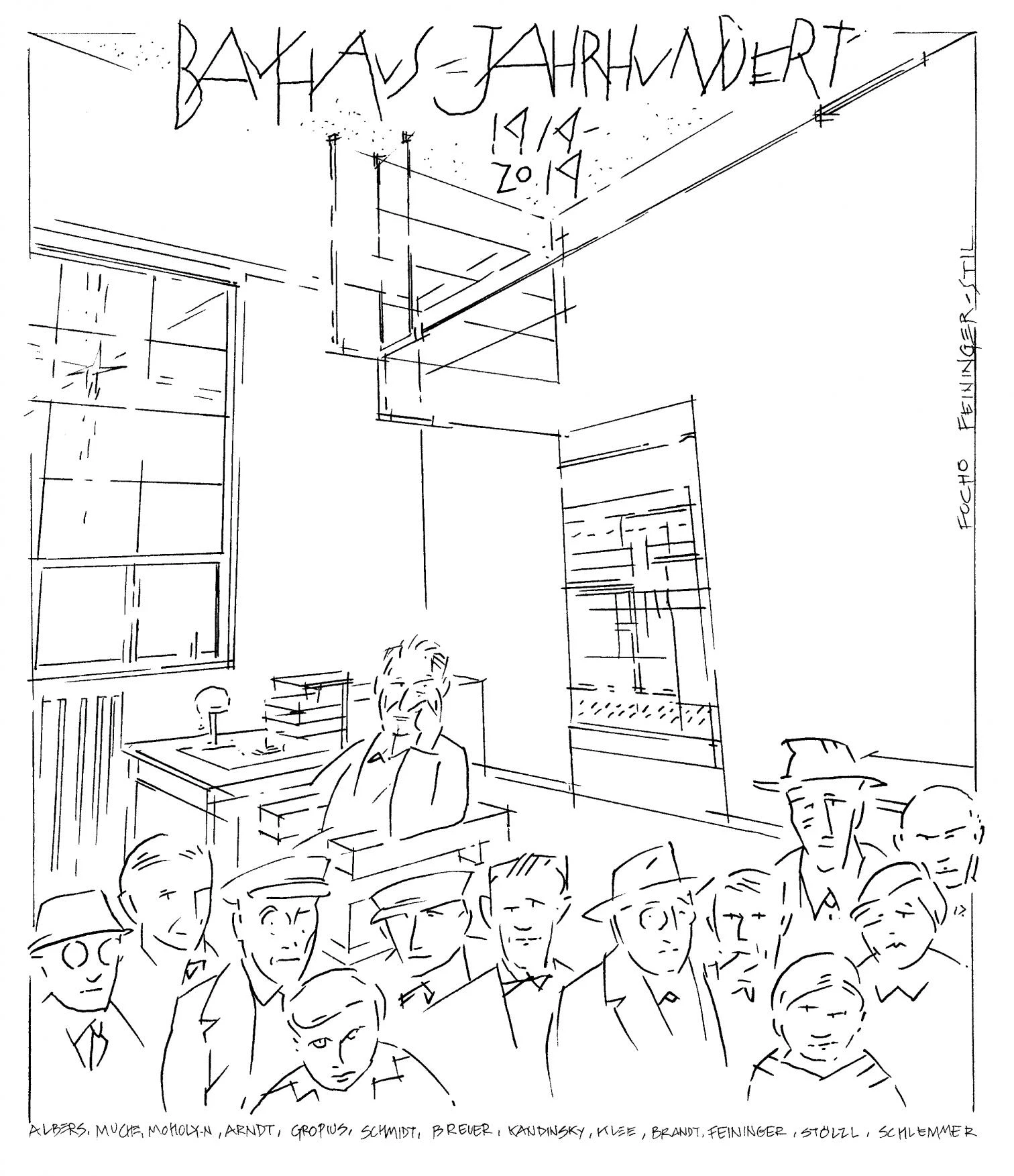

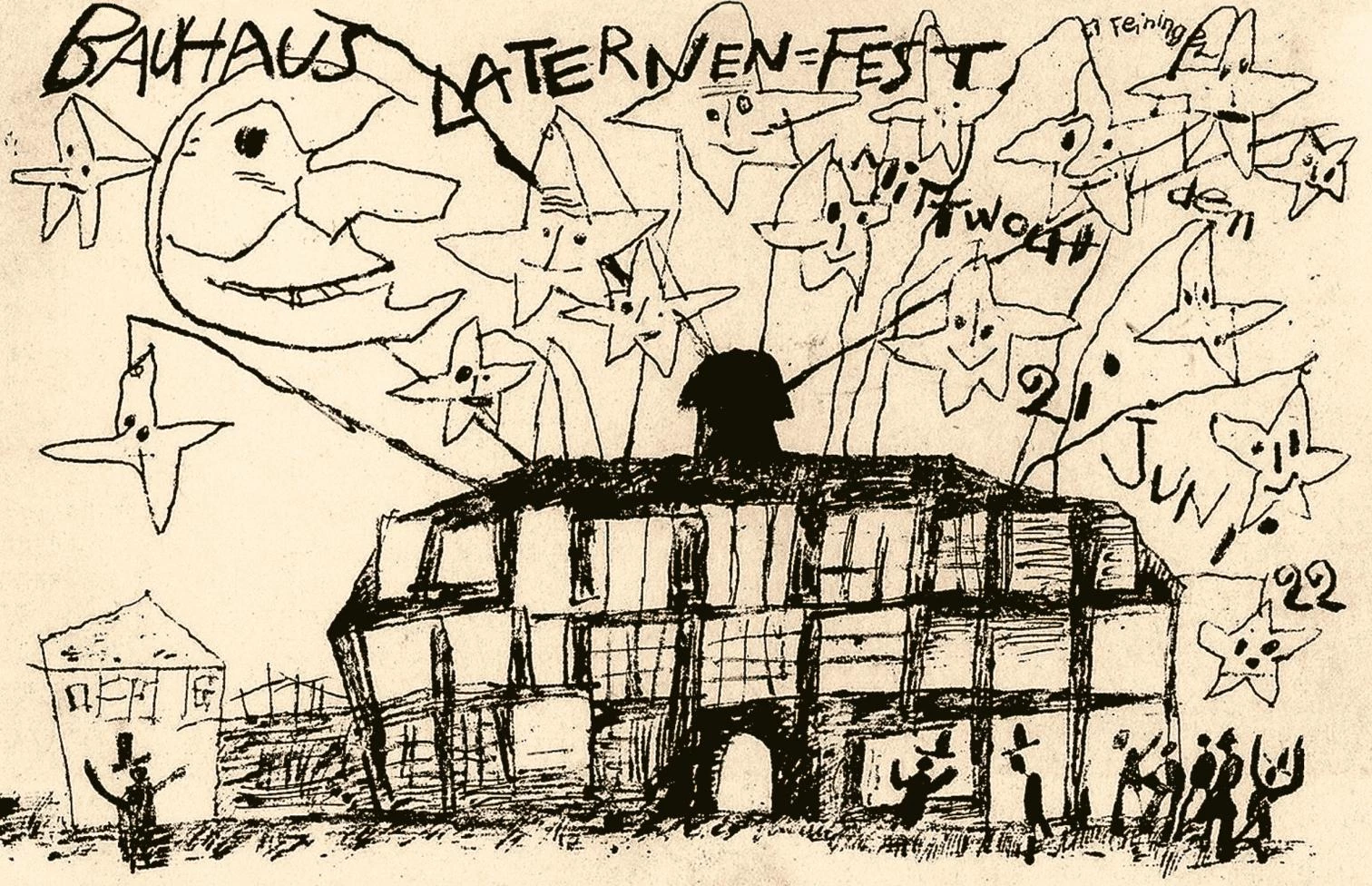

In truth the Bauhaus, founded during a very dramatic period in Germany, was a romantic endeavor sponsored by the State, which found in Walter Gropius and his followers the perfect champions for the idea that pedagogy could be the remedy for two ailments of the period: the alienation caused by capitalism, and the disconnection of art from technology. The cure, first of all, involved injecting students with large doses of romanticism by means of teachers like Itten, Klee, and Kandinsky, who introduced a very unique learning method, one based on esotericism and the modern belief in a universal design language revolving around basic shapes and colors. Later, transgression gave way as much to the fruitful moderation of a new batch of instructors – such as Moholy-Nagy and Albers, whose workshops birthed some of the great icons of modern design – as to the truncated directorship of Hannes Meyer, who steered the institution towards the concept of socialist productivism. An evolution reflecting the myriad complexities of those times.