A Civil Bastion

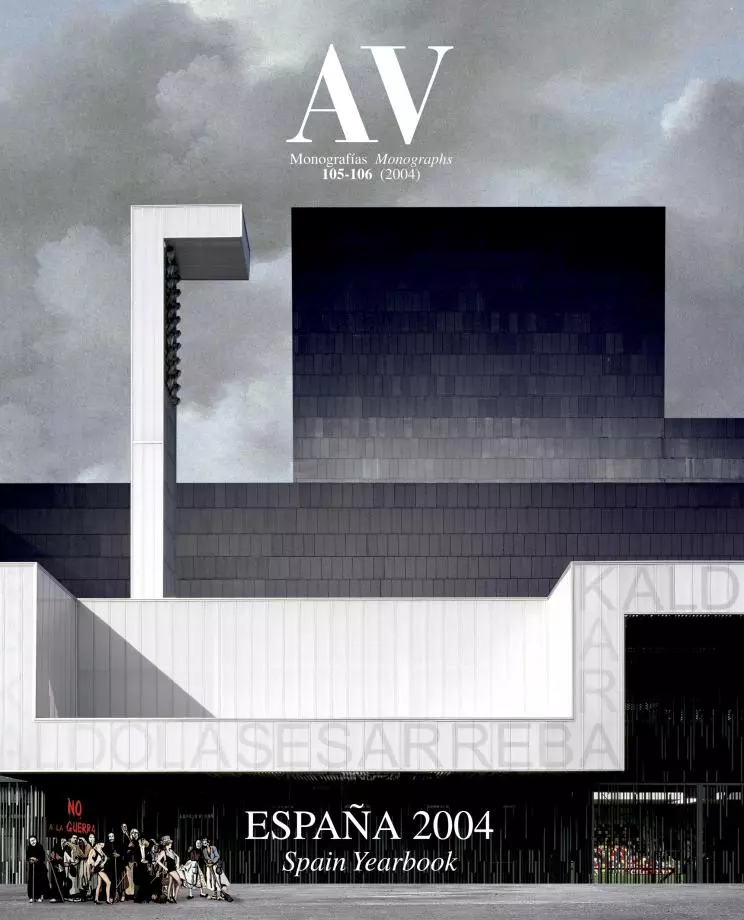

The Congress Center and Auditorium of Navarre is the most significant work by Francisco Mangado, and a singular piece of urban architecture.

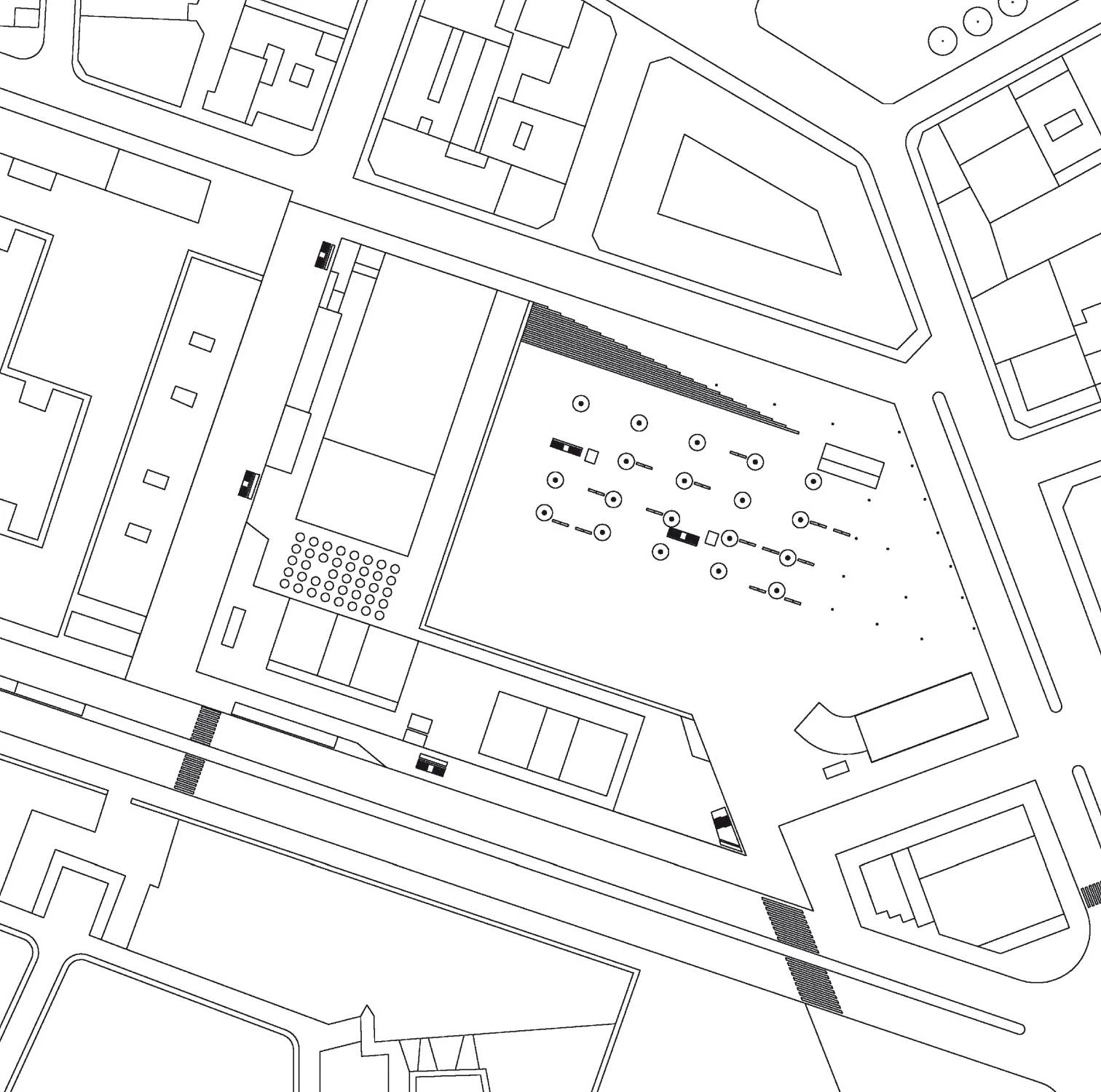

The baluarte of Pamplona is more a city than a building. Not only because its formidable scale can take in the multitudinary conglomeration of that virtual urb that participants of conventions, spectators of concerts, and visitors to exhibitions constitute, but because the project subordinates the visibility of the architecture to the protagonism of the city. Against the contemporary enthusiasm for loquacious constructions, Francisco Mangado and his team have delivered a laconic work of dark prisms that lock together in an L to adapt to the urban scheme, its arms forming a new plaza and its sober horizontal profile rising over the murmur of the city around. The data alone say much: after five years and 78 million euros spent, Pamplona and Navarra now have a cultural building with 38,000 square meters of floor space, parking for 900 vehicles, and a one-hectare public square. But if figures speak, the building is silent, and one has to cross the hermetic facade of African granite to hear the inflections of its voice in the beechwood acoustics of the halls or in the luminous dialogue between the black Indian quartzite and the red padouc wood of the communal zones, two spaces where Mangado has enriched the required regularity of the floor plans with the tactile seduction of materials or the exigent perfection of the finishes.

Strictly monochrome and rectangular, the congress center is set out as an alternative to spectacle-buildings, while its dialogue with the urban grid is expressed by the L-shaped articulation that creates a public plaza.

The result of an open competition held in 1998, the Baluarte offers itself as an alternative to spectacle-buildings, containers that impose themselves on content and context with the rhetorical violence of their uniqueness; a fever that has lost virulence among institutional clients and architects themselves but which at the time of the competition, with the Guggenheim of Bilbao just completed to great applause, was not easy to avoid. Mangado, who first attracted attention a decade ago with squares built in Olite and Estella that showed his capacity to reconcile contemporary design and historic memory, a precise wine cellar in Navarra we might consider precursor of the current profusion of signature wineries, and a residential district outside Pamplona that revealed a rare combination of formal refinement and urban pragmatism, now comes of age with the Baluarte: as a designer of furniture, lamps, and objects, which here blend into the complex with the elegant ease of his interiors and public spaces (Madrid has one of each, the recently opened La Manduca de Azagra restaurant and the almost finished Plaza de Felipe II); as an architect of exemplary efficacy in the reconciliation of functional exigencies and aesthetic demands, which here are addressed through the volumetric drama of the foyers or the silent serenity of the halls (experiences that will surely prove beneficial to his forthcoming auditoriums in Palencia and Ávila); and as an urbanist attentive to the lines and traces of the city, evident here in the way the building is inserted into it, but also in the intelligent blending of the remains of the bastion of San Antón – one of the contiguous Ciudadela’s five points – into the exhibition spaces of the complex.

Modern Realism

A prophet in his own land and an architect who builds all over Spain and beyond from his studio in Pamplona, Mangado is sometimes associated with two fellow-Navarrese of previous generations who set up practice in Madrid: the late Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza, and the disciple of his who would become the Spanish master with the most interna-tional projection, Rafael Moneo. But whereas the link between Oíza and Moneo is clear, based as it is on a shared devotion to Corbusian formalism, the connection of either of them to Mangado is more tenuous, sustained only by some strands of the stub-born eclecticism of the Kursaal’s author. Mangado fits more into a Miesian tradition tempered by re-alism and filtered by masterly epigones; one is Arne Jacobsen, who led him to the broader world of Scan-dinavian empiricism and even to the austere moder-nity of the early Aalto, who in turn, incidentally, is literally cited in the Baluarte; another is Alejandro de la Sota, inevitably absorbed through Sotians of Madrid and Galicia, or even through his influence on Catalan architecture of the eighties, and dyed by the bold neoplasticism of his training in the architecture school of the University of Navarre, where he would eventually replace Javier Carvajal as a reference figure.

Expression of the desire for continuity and change in Navarre, the Baluarte opened its doors at the same time as the house-atelier of Oteiza, next to the museum designed for the sculptor by Sáenz de Oíza (below).

Gathering 1,550 spectators around the Duke and Duchess of Lugo, Navarre president Miguel Sanz, and Pamplona mayor Yolanda Barcina, the inaugural concert starred the Navarrese soprano María Bayo, who with gay agility delivered a potpourri of songs, opera and zarzuela arias as popular as inappropriate for the singularity of the occasion, however useful for verifying the excellence of Higini Arau’s acoustics. The robust musical tradition of the land of tenor Julián Gayarre and violinist Pablo Sarasate deserved a better program, one at a par, in the architectural field, with the auditorium, which is as keen on striking a continuity with the preexisting as it is watchful of falling to that sort of folkloric vulgarity that on opening day even allowed a chotis. Conscious of its ancestral heritage yet determined to compete in the global market, Navarre modernizes with caution, providing new containers for the old stock of its historic and ethnographic memory. Examples are the General Archive of Navarre, recently finished by Moneo, and the sanfermines museum to be built by Mansilla & Tuñón. But no work expresses this desire for continuity and change better than the Baluarte, a building that is conservative in appearance but ambitious in purpose, and which by putting the hustle and bustle of conventions and concerts right in the urban center uses culture to blow life into the existing city, contrary to the usual placing of large infrastructures in the discontinuous peripheries.

Not far from Pamplona, in the village of Alzuza, the house-atelier of the sculptor Jorge Oteiza opened its doors at the same time as the auditorium, incorporating the artist’s private spaces to the building designed by Oíza that shelters thousands of pieces of his legacy, from chalks to slates, and offering a lyrical, intimate counterpoint to the choral urbanity of the Baluarte. The museum’s compact concrete volumes, crowned by three metal skylights that pierce the heavens like black heralds, were wrapped up by Oíza’s two architect offspring, Marisa and Vicente Sáenz Guerra, with the collaboration of Darío Gazapo and Concha Lapayese, and opened to the public in May, hardly a month after the death of the sculptor and three years after that of the architect. Going through the domestic spaces of the contradictory genius, the unanimous solitude of the storage rooms, and the fortress-like museum – a rough, violent itinerary that one cannot help comparing to the placid, friendly walk of its alter locus or alter domus, the canonical and cosmopolitan Chillida-Leku – one feels far from the Pamplona that is still discernible from here, attentive as it is to the civil choreography surrounding the Baluarte and aware that if poets should not rule the republic, neither should the hypocrisy of a handful of ethnicist lunatics who use anthropology as a weapon for homicide and an instrument for segregation. But go to Navarre and see it for yourself.